Widows – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on the 18th of November 2018

Fox presents a film by Steve McQueen

Produced by Steve McQueen, Iain Canning, Emile Sherman and Arnon Milchan

Screenplay by Gillian Flynn and Steve McQueen based on ‘Widows’ by Lynda La Plante

Starring Viola Davis, Michelle Rodriguez, Elizabeth Debicki, Cynthia Erivo, Colin Farrell, Brian Tyree Henry, Daniel Kaluuya, Jacki Weaver, Carrie Coon, Robert Duvall and Liam Neeson

Music by Hans Zimmer

Cinematography Sean Bobbitt

Edited by Joe Walker

Rating: MA15+

Running Time: 129 minutes

Release Date: the 22nd of November 2018

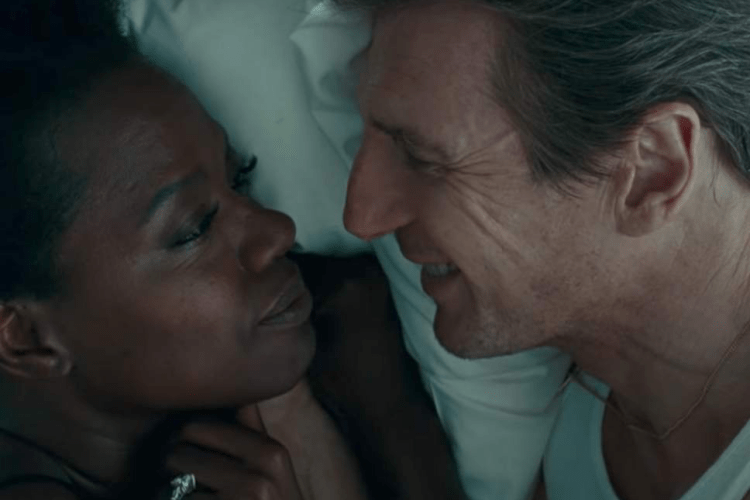

Widows explores a complex web of characters, each of whom is constrained by a capitalist, dog-eat-dog society. Set in Chicago, the film opens with a couple, Veronica (Viola Davis) and Harry (Liam Neeson), lying in bed together and intimately kissing.

The sensual flashback is juxtaposed with a violent present-day chase scene. Harry is driving a speeding van while his accomplices fire at the police from the back of the vehicle. Once inside a warehouse, all the men in the van are killed by an explosion.

The man the group has robbed is Jamal Manning (Brian Tyree Henry), a candidate in a local council election. At 37, he believes he is too old for a life of crime and is determined to enter politics.

However, his campaign needs the stolen money to survive. He hunts down the debt from the wives of those killed in the warehouse explosion. Jatemme (Get Out’s Daniel Kaluuya) is enlisted to pursue Veronica and ensure that she returns his money on time.

Knowing the likelihood of death, Veronica recruits the women to complete a heist that Harry already had planned before he died so she can repay Jamal. She relies on the notes within a diary that Harry left behind before he died.

The women are wounded in different ways. Veronica remains in her lush penthouse with her dog but still grieves for Harry. Linda (Michelle Rodriguez) is set to lose her store because of her partner’s debts. A repo man says to her unsympathetically, ‘he should have loved you more and the bookies less!’

Alice (Elizabeth Debicki), whose deceased partner was violent to her, is pushed by her mother, Agnieska (Jacki Weaver), to become an escort to support herself. Veronica also hires Belle (Cynthia Erivo), a babysitter who doubles as a getaway driver and helps prepare the heist.

The last piece of the jigsaw is Jack Mulligan (Colin Farrell), a reluctant politician contesting Jamal with his own campaign. He is only participating to fulfil the legacy of his ageing, racist father, Tom Mulligan (Robert Duvall).

Widows was directed by British filmmaker Steve McQueen who is currently one of the best directors in the world. His previous three films, Hunger (2008), Shame (2011) and 12 Years a Slave (2013), were intense character studies that dramatised physical and mental imprisonment.

McQueen co-wrote Widows with Gillian Flynn (Gone Girl) by adapting the work of English author Lynda La Plante. It is a sophisticated adult crime film on par with McQueen’s previous work. Some have described it as mainstream and a crowd-pleaser, which is misleading. While enormous in scope and offering some intense action, it is foremost a character study overflowing with visual and thematic ideas.

The volume of interesting characters and complex storylines are clearly organised by a transparent thematic core resembling HBO’s The Wire and McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave. The human condition here is defined exclusively by capitalism. Each characters’ socioeconomic background differs, but their survival is collectively unified by money.

Widows is therefore a critique of the economic strains of modern America that inevitably steers people towards criminality. There are no sanctuaries either as shown in Jamal’s flawed moral transformation, which is derailed by crime, money and violence. In one memorable moment, it is implied that the church is corrupt when a pastor asks a character what his support is worth.

Economic pressure also intertwines with the damaging pathways built by family. The most obvious example are the widows repenting for the sins of their corrupt partners who have led them to this crisis. Similarly, Alice’s work as an escort results from her being bullied by her mother, while Jack has reluctantly inherited his father’s political legacy. Jack mirrors the same passionless candidacy Jeb Bush undertook during the 2016 Republican presidential primaries. He only participated because of his family’s name.

Furthermore, family binds are apparent in a deft touch of realism when the women decide to meet again. Linda asks if it is at 11am or 11pm, and stresses the difficulty of staying out late because of her children. This typifies how these dubious characters are governed by their personal commitments and their relationships with their families.

Steve McQueen’s success as a filmmaker is attributable to his visual arts background that provides his work with cinematic panache. There are some extremely powerful scenes that benefit from his formal choices. For example, the visual design highlights the difficult emotional binary of Veronica and Harry’s complex relationship.

McQueen frames Veronica in a close-up shot while she is pressed hard against a pane of glass. The milieu and the desaturated colour tones underline the lingering grief that Veronica still feels for Harry. In contrast, the cold metal and steel furnishings of her penthouse dramatise her capitalist imprisonment, showing how Harry’s choices have concealed her within criminality.

The inseparability of sex and money is also evident in a scene where Alice has been hired to meet a man. The bar they meet in comprises of glass panels, which symbolises her emotional resistance to being bullied and sold off by her mother.

Widows‘s suitably gritty textures, apparent within its warehouse and street scenes, stress the city’s lingering poverty. The film’s most unique pieces of audio-vision reflects Jack’s attitude towards this fractured cityscape. In a moving car, Jack argues with his advisor but both characters are kept off-screen. We only hear their voices.

As the vehicle speeds along, we hear Jack begrudge his election bid and how much he hates his father. The car becomes an apparatus for the camera to sit upon so that it crabs sides and documents the desolate vision of poverty in the background of the frame. Perhaps the movement is also reflective of Jack’s desire to escape from this situation in which he is imprisoned.

Once Jack’s advisor argues ‘this is your life’, the camera moves to the other side of the hood and photographs the wealthier neighbourhood. The framing mirrors the conversation, stressing Jack’s disinterest but then underlining the wealthy, polished façade he will project and the lifestyle he will inherit if elected.

In terms of sheer visual grandeur, the biggest shot in the film is an establishment shot of a huge car lot. The wide shot frames an alarming number of vehicles for sale, which stresses the density of capitalism regarding consumer goods.

The film’s performances are predictably strong. Viola Davis is a rock-solid lead whose presence is reliably gritty but tempered by a potent feeling of loss. The reason her grief is palpable is because McQueen and Flynn have not constrained Veronica’s backstory to dialogue. Instead, they have employed vivid flashbacks that dramatise tragedy and racism.

Race is still handled in a subtle, adult way that forgoes cheap slurs and instead filters deep into the psychology and the choices of the characters and their relationships.

The two standouts from the supporting cast are Daniel Kaluuya and Elizabeth Debicki. All of Kaluuya’s scenes feel dangerous because he is highly intimidating as Kaluuya who stalks Veronica, and sometimes grows violent when interrogating people for answers.

Crucially, there is a late scene where he smiles as he listens to his boss on the radio. While subtle, it suggests that despite his violent ways he is bound to loyalty and money in the hope that Jamal’s campaign succeeds. Beware though: many of his scenes, particularly a confrontation in a bowling alley, are difficult to watch.

Australian actress Elizabeth Debicki deserves an Oscar nomination for playing Alice. In a remarkable scene, she is photographed in a tight close-up shot to show the pressure she feels from Agnieska. Debicki immediately discovers her character’s brittleness and fear during this emotional family confrontation. Yet Alice also has a strong arc where she hardens herself to become more decisive and refuses to be treated poorly.

Widows benefits significantly from a very strong script that is rich in theme and character and features sharp and surprisingly funny dialogue. The confident direction, including the consistently moody tone, the intensity of the piece and the visual choices, stems from a filmmaker unafraid to challenge his audience with confronting but layered material.

It is also buoyed by a powerful emphasis on fundamentals. The clarity of knowing who the characters are, what they want, and sometimes what they are hiding eases the burden of being overloaded with information. Instead, we become immersed in genuinely surprisingly plot twists, and the exciting climactic heist the women undertake.

I would like to see the film again to further unpack the details of its script and to relive its most powerful scenes. This is a rare critique for most modern films, but also a distinction applicable to McQueen’s very best work.

Summary: Widows benefits significantly from a very strong script that is rich in theme and character and features sharp and surprisingly funny dialogue.