Whiteley – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on the 4th of May 2017

Transmission presents a film by James Bogle

Written by James Bogle, Victor Gentile

Cinematographer: Jim Frater

Edited by: Lawrie Silvestrin

Music: Ash Gibson Greig

Rating: M

Running Time: 90 minutes

Release Date: the 11th of May 2017

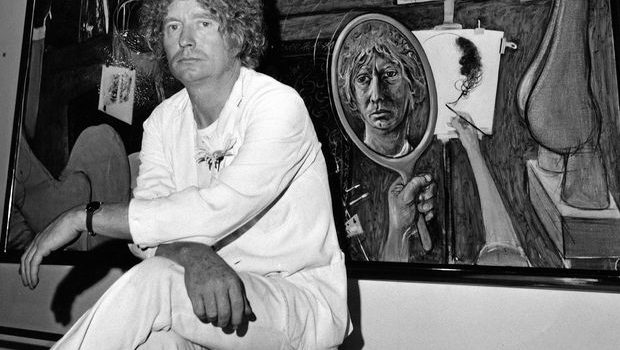

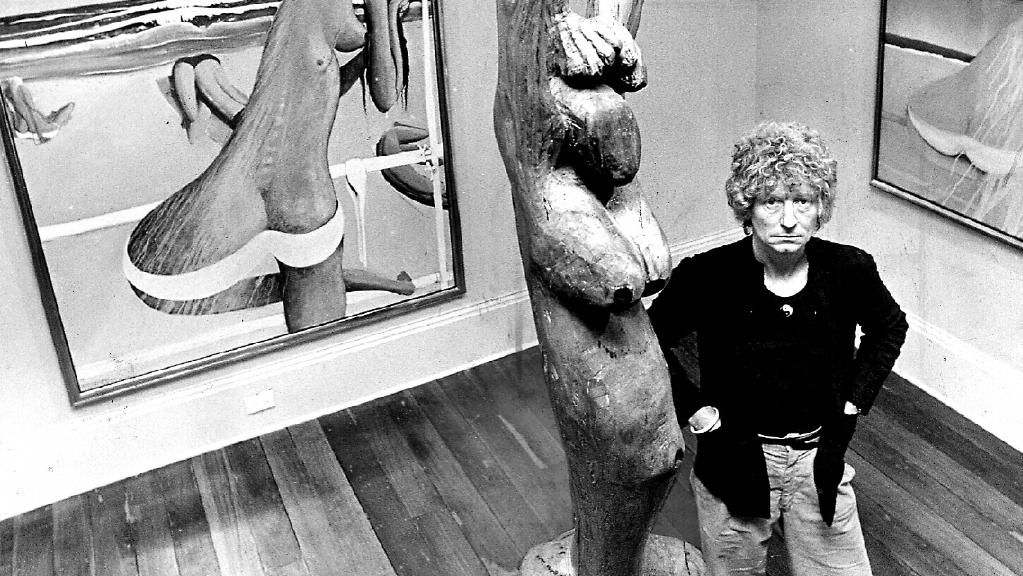

This documentary will make for a tidy, light introduction to the life and the work of Brett Whiteley for people, particularly students, who are new to his talents. At a mere ninety minutes long, the film confronts the challenge of packing an entire life of fifty-seven years into its running time. It breezes through his life events one after another to provide a brisk summary of Whiteley’s accomplishments and the ongoing relationship troubles he shared with his wife of twenty-seven years, Wendy.

Whitely is one of Australia’s most famous painters. The documentary describes his work as an act of love and one that was inspired by finding a book about Vincent van Gogh in a church after he was sent away to boarding school. As an artist, he was said to have been drawn to extremism or more specifically people living outside the normal conventions of society. Perhaps this is attributable to his own family life where he had to prove to his father that he could make a living solely out of painting.

Even in his early twenties there were raptures about his work, which provides a glowing nostalgic recount of his early talents. One person said that his work was “totally realised in depth and personal vision” for example. His work often dramatised landscapes, which were painted in a style reflective of sexuality, or more specifically and personally, his wife Wendy.

Whiteley claimed that “politics and art don’t mix”, but his time in the US during the Civil Rights Movement had a major cultural impact on his work. He imbedded himself in the progression, but also steered himself towards the accompanying culture of drugs and addiction. Drugs are said to have spurred his creativity, leading him towards some of his major work, but he was inevitably damaged as a person and in need of help.

While the film offers a linear summary of Whiteley’s life, inseparable from the struggle many artists have with drugs, alcohol and relationships, the presentation of this information is buoyed by a surprising amount of visual panache. The film thankfully doesn’t lull on talking heads and static interviews but employs a wide range of audio-visual techniques, including still photographs, stop animation, pop-up art, voice over actors playing Whitely and his wife, and archival footage of Whiteley himself.

One example of flair is the use of an illustration as a background shot but then in the foreground of the frame an animated person stands so that the image achieves a pop-up art look that doubles as an imaginative ode to the multi-dimensional depths of Whiteley’s work. Other moments are more traditionally filmic in using the cinema scope to heighten the size and depth of some of the images. The incredible American Dream piece is sumptuously photographed with the camera panning from right to left so that we fully appreciate the scope of the mural and the amount of detail in the entire piece.

By employing a varied, experimental visual style, the film is elevated above the blasé presentation of some television documentaries released at the cinema. It is also imperative for the visuals to carry the film as compensation for the hurried way in which it compresses and crops an entire lifespan into its brief duration. Regardless, it’s an informative summary and one that is stimulating to look upon.

Summary: An informative summary and one that is stimulating to look upon.