While We’re Young – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on April 13th, 2015

Roadshow presents a film by Noah Baumbach

Produced by Scott Rudin and Noah Baumbach

Screenplay by Noah Baumbach

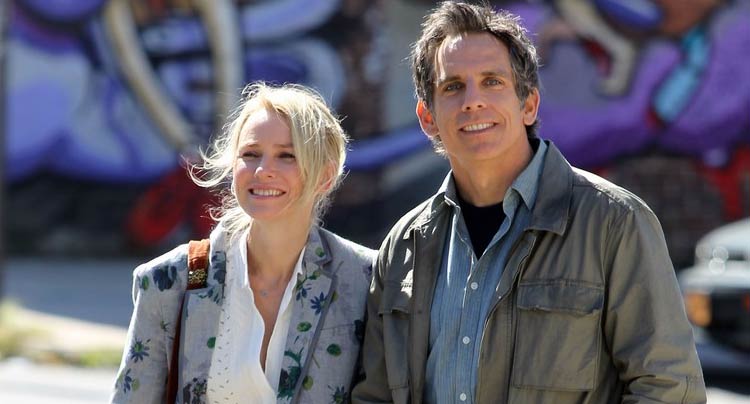

Starring Ben Stiller, Naomi Watts, Adam Driver and Amanda Seyfried

Music by James Murphy

Cinematography Sam Levy

Edited by Jennifer Lame

Running Time: 97 minutes

Rating: M

Release Date: April 16th, 2015

Noah Baumbach’s slice of life comedy While We’re Young is self-indulgent, but not in a negative sense. The films Baumbach has made are generally interesting ones about everyday life. These films include Frances Ha, The Squid and The Whale and Greenberg. At their simplest, each is about finding humour and drama in relationships and friendships. Baumbach’s latest feature opens with a quote from Henrik Ibsen’s play “The Master Builder” and also channels Woody Allen tropes such as consumerism, male envy and the documentary plot device from Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989). As he approaches middle age, this is also perhaps Baumbach’s most autobiographical film. Aged forty-five (a year older than the film’s lead character), Baumbach is dating actress Greta Gerwig, the thirty-one year old star of Frances Ha. Potentially, this age gap pressed Baumbach to ask questions about generational splits and the defining experiences of a person’s life. Throughout this peculiar and hilarious film, the answers to Baumbach’s questions are found in ideologies and political rhetoric, which he believes people subscribe to in their relationships. It takes time understanding the director’s intentions for the film but the characters and their values are worth an extensive discourse.

Ben Stiller (the star of Greenberg) plays Josh, a forty-four year old lecturer living with his wife Cornelia (Naomi Watts). She wants to be spontaneous but he is much more rigid about making plans. They have suffered due to Cornelia’s series of miscarriages. At a class Josh is giving he meets an enthusiastic couple, aged twenty-five, who show great interest in Josh’s filmmaking work. They are Jamie (Adam Driver) and Darby (Amanda Seyfried). The two couples befriend one another and spend sizable amounts of time together. Jamie and Darby’s love for retro things like records and handmade furniture becomes infectious for Josh and his wife. He believes in their energy and enthusiasm but strange occurrences like at a Sharman session together rock the boat. Josh also grows jealous of being unable to finish the documentary he’s worked on for a decade, while Jamie’s film involving Facebook and someone from his childhood continues to flourish.

One ideological reading of the film is in the contrasting political stances Josh and Jamie represent. The gullible nature of Josh and enthusiasm for the young couple breaks down potential social barriers and divisions between their ages. He sees Jamie not as inferior for being younger than him but his equal. The friendship between the couples, from Josh’s perspective, could be interpreted as Marxist rhetoric combined with social conformity. Josh and Jamie dress similar, meet the same people and bike ride together. Darby and Cornelia aren’t separated by age either but partake in a hip-hop dance class. Josh and Cornelia are also impressed by the possessions and taste of the couple, including the extensiveness of their record collection. These items reflect how divisions in both class and age are dissolved as both couples enjoy these experiences. The film’s soundtrack reflects a cultural and class-based symmetry by switching between a classical piece, Vivaldi’s Mandolin Concerto in C major, and rap music like “Buggin’ Out” by A Tribe Called Quest. Throughout the narrative conflict develops by dispelling the Marxist rhetoric, foreshadowed by a gag where Josh must collect the bill and his prolonged failure to adopt modern capitalist instincts. His documentary highlights his cultural and political stasis: it is an overlong, self-indulgent mess, which he refuses to cut after rejecting editing advice from his father-in-law. His stubbornness emphasises a desire to retain his imprint over his work, rather than succumbing to the mass product, which results in him failing to express its purpose to an obnoxious financier. This comic side character possibly represents the single-mindedness of the Hollywood capitalist machine – perhaps an expression of Baumbach’s own frustrations as an indie filmmaker.

The character Jamie represents youthful, self-preserving capitalist enterprise, concurrent with post-GFC culture and the ruthless characters of contemporary films like The Wolf of Wall Street, The Great Gatsby and Nightcrawler. Darby concedes Jamie’s self-absorbed nature. He is willing to cross social boundaries and consume people as his own, like during a confrontation at the Sharman meeting where Cornelia mistakes him for Josh and kisses him. Similarly, for his film he collects other people’s experiences and memories, passing them off as his own findings. The records and handmade furniture he owns are ornaments of someone else’s past rather than possessions representing personal life experiences. One example of him inventing emotion is asking Josh to replay a scene of discovery after he fails to initially capture it on camera. Therefore, he uses other people’s experiences, contacts and emotions to fulfil his capitalist dream of filmmaking, deemed artificial by Josh, but one which the backers find comparatively accessible. Through the film’s political discourse and conflict of ideologies, pitching Marxist-like rhetoric against self-preserving capitalism, Baumbach stresses the loss of personal imprint in one’s work, with mature life experiences becoming overshadowed by the consumerist values of a young, ambitious generation.

On an impressionistic level While We’re Young is enjoyable due to the humour and the quality of Ben Stiller’s leading work. In Greenberg he gave one of his best performances and this role is hysterically funny in a straight-faced, quiet manner. He is playing a man desperate to believe in the people around him and hoping to reinvigorate his relationship with his wife. Naomi Watts, her character often visibly distressed, has a memorably touching moment where she reflects on how much more they could have achieved in their lives. They reach the sentimental conclusion that their strongest memory is in each other. The only complaint with the film is despite its enjoyment, it’s not a film driven by plot or incident. In the final quarter the film adopts a conspiracy-style parody plot which is slightly convoluted and disjointed. This might be deliberate in keeping with Josh’s paranoia and frustration, which hilariously amounts to nothing in the eyes of the other characters. While a strange film with quibbles, the ending is note-perfect. The image of a child cradling a mobile phone summarises Baumbach’s concerns for young people drawn into a highly commercial, capitalist world. It’s one which they may not initially understand but will gradually adapt towards and manipulate to survive.

Summary: Throughout this peculiar and hilarious film, the answers to Baumbach's questions are found in ideologies and political rhetoric, which he believes people subscribe to in their relationships.