Vice – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on the 28th of December 2018

eOne presents a film by Adam McKay

Produced by Brad Pitt, Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, Megan Ellison, Kevin J. Messick, Will Ferrell and Adam McKay

Written by Adam McKay

Starring Christian Bale, Amy Adams, Steve Carell, Sam Rockwell, Tyler Perry, Alison Pill and Jesse Plemons

Music by Nicholas Britell

Cinematography Greig Fraser

Edited by Hank Corwin

Rating: M

Running Time: 132 minutes

Release Date: the 26th of December 2018

A disgusting monster possesses a mentally weak man and controls his actions before it can be shot back into space. This is the plot of Venom (2018), but it is also applicable to Adam Mackay’s Vice. It is a mediocre biopic about former Vice President Dick Cheney, the reptilian figure who silently manipulated George W. Bush throughout his presidency during the early 2000s and persuaded him to undertake the War on Terror.

The film is comparable to Venom because we must ask how such a villainous figure became the main protagonist of a film. A good movie must have a hero or anti-hero to whom we can relate, and a great villain must continually overpower the protagonist until the end. This is not to say that Vice paints Cheney as a good person. Instead, by reversing or diluting the roles of the hero and the antagonist, a narrative void occurs where empathy and obstacles would normally be placed.

To be fair, McKay’s filmography has always placed wicked men at the fore. He has directed several Will Ferrell vehicles where the comedian played characters who believed they were smarter than they were. The most popular example is still arguably Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy (2004). The Big Short (2016) saw McKay transition from fun mainstream comedies to a self-declared political expert. With Short, he clumsily attempted to examine the flawed men involved with Wall Street and the GFC.

Vice, starring Christian Bale as Cheney, continues his exploration of terrible men of power but fails to transcend its conventional biopic framework. It does not provide enough new insights into this period of political unrest to justify Cheney as its leading man. McKay’s fussy visual gimmicks also detract from the rich cast, which includes Amy Adams, Steve Carell, Sam Rockwell and Jesse Plemons.

The opening scenes are inseparable from Oliver Stone’s weak Bush biopic W. (2008). In identical fashion, the story cuts from the White House back to Cheney’s youth. Like Bush, Cheney is a blue‑collar worker on an oil rig and an alcoholic in trouble with the law who is salvaged by the love of his wife, Lynne Cheney (Adams).

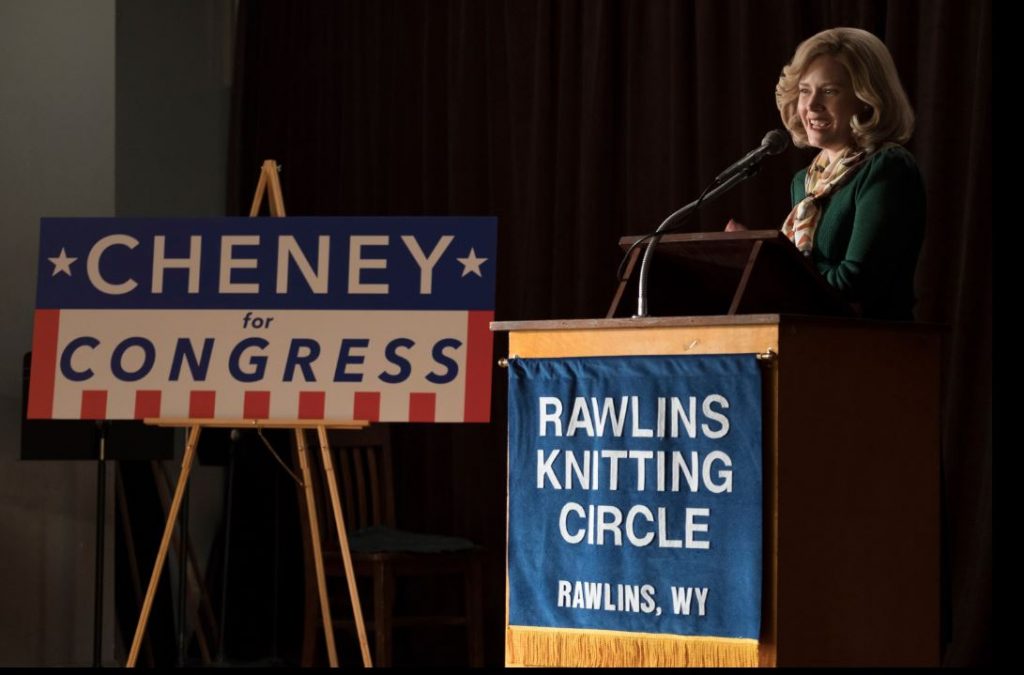

In the first quarter, Lynne proves to be a more interesting figure than her husband. A quick intercut reveals that she grew up in an abusive household. It is an experience that she wishes to leave behind as an adult. Consequently, she continues to campaign for Cheney’s Congress bid while he is troubled by his ongoing heart problems.

He soon works in politics as a naive intern for Donald Rumsfeld (Steve Carell) and then the film forwards to when he is a seasoned campaigner in the twilight of his life. He is asked by Bush (Rockwell) to become his Vice President. He tells Lynne that Bush is ‘green’, implying he is easily led. This leads to disastrous decisions, including the policy to invade Iraq based on false pretences.

Instead of trusting his actors with a ‘less is more’ approach, McKay’s direction over-complicates the simplest of scenes. For example, there is a meeting between Bush and Cheney where they sit at a desk. McKay overloads the scene with extreme close-ups of eyes, fingers tapping on the desk and needless cutaways to fishing lines to symbolise Cheney reeling in his man. The entire film is also pointlessly narrated by Jesse Plemons’ mysterious character who breaks the fourth wall and talks to the camera.

If the reoccurring fishing shots are intrusive, there’s also quick cuts of war footage and an unnecessary montage of Cheney’s heart surgery. A huge gap in Cheney’s chest loudly telegraphs his dehumanisation. Other moments attempt to lace comedy into the tired biopic structure. There’s a clever, albeit gimmicky, moment where Vice feigns conclusion with a fake credit sequence. Although the film isn’t consistently loaded with funny quips for it to be deemed a comedy.

Another key moment typifies the sledgehammer approach of McKay’s filmic style. There’s a scene where the Cheneys are at a party together and Lynne declares how everyone either fears them or wants to be them. Later in bed, the couple talk to one another in Old English. It is as though McKay narrowly resisted writing ‘Shakespearean’ on the camera lens. The intertextuality feels laboured after watching several seasons of Netflix’s House of Cards.

In the second half, McKay abandons his faux attempt to reinvent the biopic genre with intercuts and gimmicks. The film lazily recounts each political atrocity with dull chronology, including the Iraq War, the tax cuts, and the implementation of the Patriot Act. This section tells us little that most of us did not already know and merely serves as a refresher. Though Cheney’s daughter being gay and his resistance to tamper with anti-gay legislation in a talk with Bush is smartly included.

Cheney argues he was willing to do everything to protect his family after the September 11 terrorist attacks. The irony of him not supporting his gay daughter because it would hinder his other daughter’s political ambitions is a belated but interesting aside. Its impact is buried beneath a flurry of visual trickery and the laborious recount of the administration’s well-documented failings.

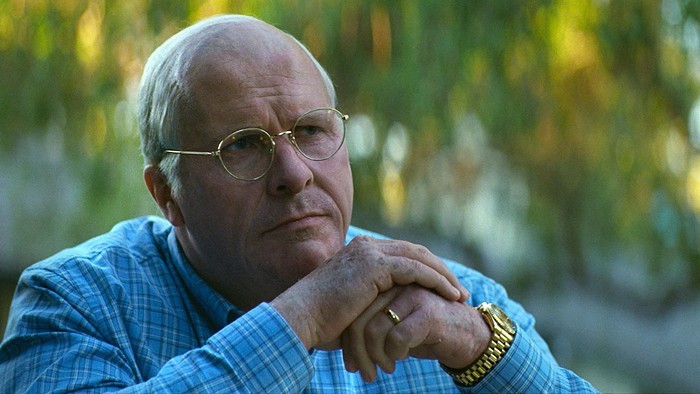

The performances do not live up to the award season buzz. Christian Bale’s physical transformation and make-up as the older Cheney are extraordinary. However, the material limits the depth of his unusually one-note performance. The scene between Cheney and Bush shown in the film’s trailer typifies the low-key baritone growl he constantly employs and the languid demeanour of the character. Aside from Cheney being morally bankrupt, who thought that a man determined to be invisible would make for an interesting lead? It would be like casting Mike Pence in a delightful romantic comedy.

There is a creepy scene during the end credits where Cheney talks directly to the camera. We feel the full weight of him justifying his terrible actions and his refusal to flinch under the pressure of our judgement. Admittedly, the moment lingers with power but it also typifies what an ice cold and overly introverted performance it is. Additionally, Cheney’s lead role means he runs through scenes without resistance from other characters. The lack of a counterpoint echoes similar narrative flaws in an early season of House of Cards where Frank Underwood rolled everyone unopposed.

While Amy Adams has some interesting scenes as Lynne, one must ask what this extremely likeable and gifted actress saw in playing a conservative monster. The woman gasps in horror upon realising that Richard Nixon may resign. Adams’ introduction to the character is also surprisingly clunky. Thankfully, the context into her upbringing helps to make her character active such as her participation in Cheney’s campaign efforts.

Sam Rockwell has a funny opening scene as Bush where a plate crashes to the ground and Cheney turns to see that he is already drunk. One would expect Rockwell to quickly steal the rest of the movie because of his natural charisma and humour. It is a mystery then as to why McKay, a comedic director, does not mine the actor for more of his adept comic timing.

The same can be said for Steve Carell whose incredible make-up as Donald Rumsfeld is equally as good as Bale’s transformation. He has a strong early scene where he continues laughing manically from behind a closed door after Cheney asks him his political position. It is the type of black, cynical comedy that could have permeated if these side characters were given more interesting scenes. Bizarrely, Condoleezza Rice, who was crucially the US Secretary of State, barely registers here. If you have noticed how much Rex Tillerson was in the news recently, it should tell you the importance of this position.

Vice ends with a strange final scene where a focus group talk about films and again break the fourth wall. It erupts into a fight between two men, one conservative and the other progressive. The argument is meant to highlight how it does not matter what information people are given because it will not change their political beliefs.

One character dimly says they would rather watch the new Fast and Furious movie instead. McKay’s cynicism underestimates his audience again. While the crimes of the Bush administration should never be forgotten, many will already be familiar with a lot of the history covered here. As proven in Michael Moore’s excellent documentary Fahrenheit 11/9 this year, the US has faced countless new crises in the last two years that people want to expose rather than retreading old wounds.

As far as sophisticated entertainment is concerned, there is a newly released film called The Favourite. It is funny, original and complex in showing political manipulations, schemes and misguided love. It has already been a success with US audiences too. It is everything that Vice would like itself to be, or better put, everything that McKay thinks his film is.

Summary: It does not provide enough new insights into this period of political unrest to justify Cheney as its leading man. McKay’s fussy visual gimmicks also detract from the rich cast.