The Theory of Everything – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on February 5th, 2015

Universal Pictures presents a film by James Marsh

Produced by Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Lisa Bruce and Anthony McCarten

Screenplay by Anthony McCarten, based on Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen by Jane Wilde Hawking

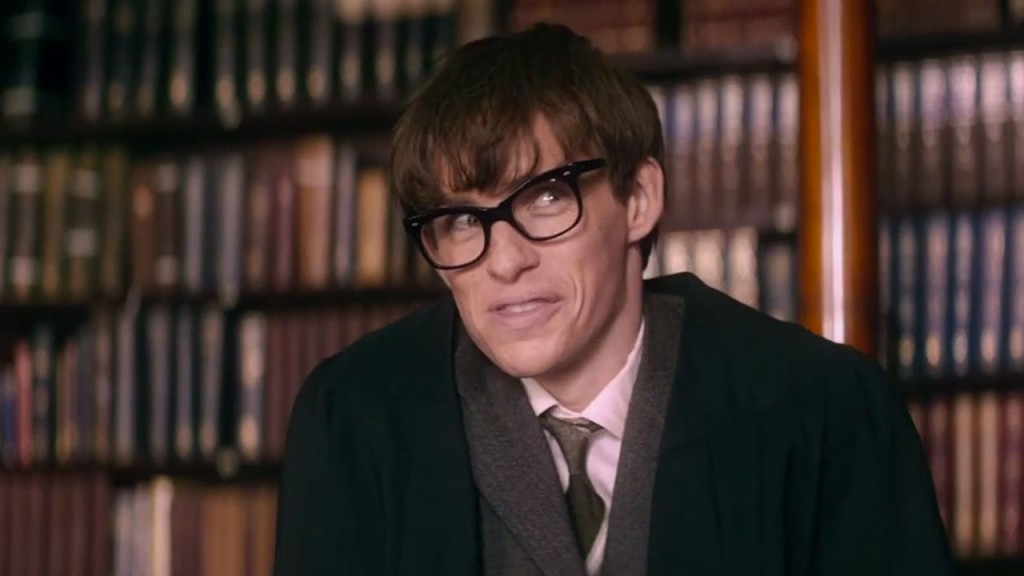

Starring: Eddie Redmayne, Felicity Jones, Charlie Cox and Emily Watson

Music by Jóhann Jóhannsson

Cinematography: Benoît Delhomme

Edited by Jinx Godfrey

Running Time: 120 Minutes

Rating: PG

Release Date: January 29th, 2015

The Theory of Everything is directed by British filmmaker James Marsh, who described the film not as a biopic of Stephen Hawking but a love story between the great scientist and his former wife Jane Wilde Hawking. Marsh previously made the documentaries Man on a Wire and Project Nim, which was about a chimpanzee taken into a human family. His new film was adapted from Jane Hawking’s book by screenwriter Anthony McCarten. The story traces Hawking’s life from when he is a highly talented, slightly lazy university student working on a PhD theory. On campus, he forms a relationship with Jane (Felicity Jones) who is studying Arts and unlike him she believes in God. He is then struck down by a neuron disease, which cripples him and leaves his entire body paralysed. McCarten’s script is mostly linear, with only one subplot, and provides little context for one of its main characters. Details about Jane are scarce outside of her Church values and love of poetry. Her mother for example (Emily Watson) only features in one scene.

Jane herself is viewed more as a symbol, an emblem of female resilience, gradually worn down by her responsibilities for her husband and unable to study. His family has more contextual detail, including his father who seems callous at times and suggests Stephen will require full time care. Their young children though are excluded from having a viewpoint about their father’s disabilities and the same is true of Stephen’s friends. They’re shown as accepting him as who he is, which dilutes the drama conflict from resonating. The only time the film becomes a conflict of viewpoints is after finally introduces Jonathan (Charlie Cox), a choir master. Jane develops a bond with him not only because of the Church but collective suffering as he lost his wife to cancer. Hovering over the film is a question of the limitations of Christian values like kindness and selflessness: how much can a person give before diminishing their own wellbeing?

The film could have dramatically reinforced this idea by not being so polite about Hawking’s limitations and the strains his condition placed on others. The narrative is coy on details about the impact Hawking’s illness had on his life, such as social functions and his daily rituals besides his general immobility. At most we see him playing noisily with the children, disrupting Jane while she’s trying to study. Instead, the film is a broad summary of his life events and bizarrely shaped like an underdog story where his personal achievement wins out against the odds. The final sequence in front of an auditorium postures as a motivational slog about how people can continue their lives together through contrasting values or in the face of great pain and suffering. “However bad life may seem, there is always something you can do, and succeed at”, he says. It’s a generic, encouraging message of individualism designed to position him as a symbol of hope and resilience, like his wife. But isn’t it also blind to the rarities of his abilities? Could anyone else in the same position as him accomplish half as much without matching his intellect?

Also surprising is despite the hype Felicity Jones’ performance is somewhat one-note because the character is more of an idea than a fully realised person, the archetype of the troubled wife used to question how selfless can someone remain in a relationship. But no one can doubt the physicality of Eddie Redmayne’s performance, which is all the more impressionable given how much he resembles the real Hawking, and rates as one of the film’s few remarkable aspects. Hawking has given the performance and the film his seal of approval, calling it broadly truthful, which alone might be satisfactory to the filmmakers. While it might not have been as flattering as making an underdog story, more specificity and insight into treating the condition daily would have been impressionable instead of skimming through his life events.

Summary: More specificity and insight into treating the condition daily would have been impressionable instead of skimming through Hawking's life events.