The Sisters Brothers – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on the 27th of March 2019

Universal presents a film by Jacques Audiard

Produced by Pascal Caucheteux, Gregoire Sorlat, Michel Merkt, Michael De Luca, Allison Dickey and John C. Reilly

Screenplay by Jacques Audiard and Thomas Bidegain based on ‘The Sisters Brothers’ by Patrick deWitt

Starring John C. Reilly, Joaquin Phoenix, Jake Gyllenhaal, Riz Ahmed, Rutger Hauer and Rebecca Root

Music by Alexandre Desplat

Cinematography Benoît Debie

Edited by Juliette Welfling

Rating: MA15+

Running Time: 122 minutes

Release Date: now showing as part of the French Film Festival

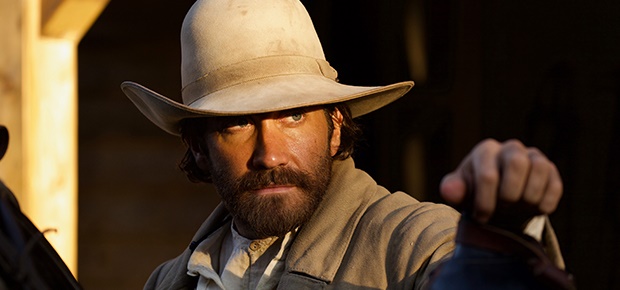

John C. Reilly is the best part of The Sisters Brothers, the English-language debut of French filmmaker Jacques Audiard. While typically cast in broad comedies and undertaking voice work in Disney’s Wreck-It Ralph series, Reilly is now a versatile character actor appearing in a variety of genres.

He has created sympathetic parts in thrillers, such as We Need to Talk about Kevin (2011), and dramedies, including The Lobster (2015) and Stan and Ollie (2018). His disarming on-screen presence and comic timing invites us to sympathise with the most dubious characters. His engagement buoys this traditional Western but its derivative themes and experienced cast, including Joaquin Phoenix, Jake Gyllenhaal and Riz Ahmed, fail to match his excellent performance.

Audiard and co-writer Thomas Bidegain have adapted Patrick deWitt’s novel. It is about Eli and Charlie Sisters who in 1851 are brothers, assassins and business partners working across the American frontier. Their father, deceased, was mad and a drunk. The Sisters are first seen killing men on a farming property. Their weapons ignite the darkened sky with quick bursts of gunfire. After the battle, the barn catches alight.

Eli (Reilly) is more sympathetic than Charlie (Phoenix) and tries freeing the animals. The Sisters are then handed their next assignment by a shadowy figure named The Commodore (a barely seen Rutger Hauer). They are hired to kill Hermann Kermit Warm (Ahmed), a chemist with a formula for locating gold. Their contact, Morris (Gyllenhaal), has befriended Hermann with the intent of capturing him.

Audiard is an accomplished filmmaker who has consistently explored violent actions. A Prophet (2009) dramatised a prisoner haunted by the person he murdered. Rust and Bone (2012) saw a woman fall for a boxer and Dheepan (2015) explored the violent clashes between vigilantes and migrants.

The thought of this brutal, transcendent director crafting a Western is exciting. However, the source material appears cliché and Audiard has been unable to shape it with his own imprint. The characters and thematic goals do not achieve the originality of his best work. It is competently made but also derivative and lacking a strong ending.

The central conflict is the tug-of-war between the past and future of the American frontier. It is a worn staple explored throughout Westerns and even gangster films. One character is lured by ‘going straight’, while another embraces crime because it shields him from modernity’s changing landscape. Clint Eastwood’s revisionist Western Unforgiven (1992) explored this idea through a failed pig farmer who returned to being a ruthless killer.

Rockstar Games’ Western-themed video game Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018) brought new insights to the dramatic premise. The game’s lead character, Arthur Morgan, was an outlaw who developed a conscience but found it impossible to be pure because violence aided his self-preservation. Additionally, HBO’s sci-fi series Westworld (2016) showed how personal agency and morality was diluted by the creators of an advanced amusement park.

Comparatively, Brothers is too conventional to explore new angles. An example of its complacency is apparent in how it handles the characters’ personal lives. For example, Eli’s desire to romance a school teacher is expressed through his dialogue with Charlie. By hiding the teacher, fresh insights into his inner life are reduced to typical Western banter. Though Eli still captures our sympathy because his personal reform is undermined by Charlie’s recklessness. Charlie is a violent, impetuous drunk who loudly announces the name, ‘the Sisters brothers’, to scare people.

The leads lack balance and there’s little distinction from other films about good people tied to wicked families. Charlie is an irredeemable sketch, which provides no reason to care about him. The characters of Hermann and Morris do not engage either. They are constructs designed to talk about a democratic society that is free from money. It is a familiar debate about whether America is solely governed by myths and lies. As such, the characters are not as empathetic or humane as they were in Audiard’s other work.

Audiard’s direction of Brothers is more workmanlike than inspired. Though he proves that Spain is a great substitute for the frontier. The beauty of the landscapes, including the mountain ranges and streams bathed in natural lighting as the horses cross them, are impressively captured by cinematographer Benoît Debie. In contrast, some action scenes, including one in a barn, are muddy and the framing makes it hard to locate the actors. The tension and realism are not sustained either due to flat pacing and Eli outgunning multiple enemies while Charlie is drunk.

Reilly’s performance stands out while the other actors are under-served. He is highly sympathetic as Eli, who is conflicted but also funny. His tepidness towards modernity is expressed through a humorous motif of buying a toothbrush but not understanding its use. There is also a funny scene where instead of sleeping with a whore he asks her to present him with the teacher’s scarf as though he is giving her acting lessons. However, our fondness for Eli also imbalances the Sisters.

There is a powerful moment where Eli warns someone that he will never betray Charlie. It emphatically stresses that nothing will separate the duo. The film persists with this line, bounding itself to their brotherhood without a revelation. When Charlie is wounded, Eli’s dilemma about leaving him is a flicker of contemplation. The decision is foretold, which narrows the depth of the story and character arcs. Meanwhile, Phoenix remains an incredible method actor, but the script deters him from finding relatable or sympathetic traits in Charlie. Phoenix now has an extensive gallery of dishevelled characters that some variations are long over-due.

Jake Gyllenhaal speaks with an old-fashioned accent befitting of the period. His voice sounds more authentic that the modern dialogue of the other characters. However, both he and Ahmed are not stretched by their roles and the arc of their relationship is predictable. There is only one important female, a hotel owner named Mayfield (transgender actress Rebecca Root). Her fate is gratuitous and unnecessary. The only other female appears at the end and casting a well-known comedian is distracting when hearing her raspy voice.

Brothers’ uninspired thematic goals are further hampered by a comically bad finale verging on parody. Eli’s moral predicament, to leave his brother or perpetuate a cycle of violence through loyalty, ends on a whimper. It is a horribly contrived, feel‑good ending that typifies the film’s resistance to insight. Perhaps if Brothers invested in its characters earlier, a stronger finish could have emerged. Similarly, a story twist could have upended the predictable themes of this genre. It is a competently made Western that is elevated by its scenery and Reilly’s impressive performance. However, it lacks originality and inspiration. It is a story about the past that is also constrained by history.

Summary: It lacks originality and inspiration. It is a story about the past that is also constrained by history.