The Lighthouse – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on the 13th of February 2020

Universal presents a film by Robert Eggers

Produced by Rodrigo Teixeira, Jay Van Hoy, Robert Eggers, Lourenço Sant’ Anna, and Youree Henley

Written by Robert Eggers and Max Eggers

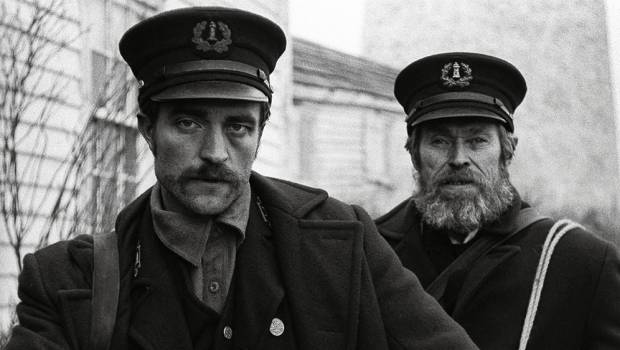

Starring Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson

Music by Mark Korven

Cinematography Jarin Blaschke

Edited by Louise Ford

Rating: MA15+

Running Time: 110 minutes

Release Date: the 6th of February 2020

Robert Eggers answered the call to find an exciting new voice in Hollywood. His debut film, The Witch, was an unforgettable gothic horror feature. Despite the difficulty of its language and its unique imagery, it was a surprise hit with audiences. It earned US$40 million dollars off a meagre budget. The film continued the gothic stylisations and evocations of authors that Eggers mirrored throughout his early short films, such as Edgar Allen Poe. Some have eagerly anticipated Eggers’ follow-up, The Lighthouse, which he also wrote with his brother, Max Eggers. The film shares several of The Witch’s stylistic properties and is elevated by strong work from its leads, Robert Pattinson and Willem Dafoe. However, its ambiguity, especially the bizarre ending, makes it less satisfying than Egger’s directorial debut.

As a former theatre director, Egger’s decision to stage the narrative in a confined space is fitting. It is about two men in the 19th century who are working together in a lighthouse on an island off the coast of New England. Winslow (Pattinson) is a newly arrived lighthouse keeper or ‘wickie’. He has come from Canada after working as a timberman. He stresses the need to abide by the book but is suppressed by his grizzled boss, Thomas Wake (Dafoe). Wake bullies Winslow into completing strenuous labour tasks and pulls pranks on him. There is great animosity between the two men, especially when it is apparent that due to the bleak, oppressive weather their contracts are suddenly prolonged, and they’re now trapped. Strange abnormalities also occur, including Winslow being bullied by a seagull and terrible nightmares of a dangerous mermaid.

Eggers’ experience as a production designer is apparent throughout his faultless visual panache. The Lighthouse is reminiscent of a classic gothic painting. Shot in black and white and filmed in the 1.19:1 box aspect ratio, the film effortlessly uses its visuals to build a rich and deeply oppressive atmosphere. The lighthouse structure itself is surrounded by a smothering fog that imprisons and isolates the men. Filming in black and white further amplifies the density of the air and the reduction of sunlight. The muted visuals and oppressive naturalism reinforce the notion that cosmic forces keep the men stranded.

Similarly, the use of deep shadows renders the film as a composite of horror features from the silent era. Eggers is skilful in building tension and then withdrawing at precise moments, such as when Wake appears behind Winslow while standing in a doorway, or quick cutting to a disturbing image of a mermaid. The shadows also reflect how the moral ambiguity of the characters shifts as we understand their backstories, including why Winslow left Canada after an accident. Wake also mumbles about once having a wife. The lines of empathy do not blur so much as reverse within the tense power struggle.

The highly tactile filmic style evokes some of the most memorable visuals. One notable example is that the lighthouse itself was a hand-built set. There is a memorable set piece where the camera captures the intricacies and gears of the inside as it ascends to the top of the structure. It also underlines the height of the building and the depth of Wake’s power. A key conflict in their power struggle is that he will not let Winslow into the top room where he’s hiding something and masturbating through a grate.

Another example of the tactility that adds tension and drama is the physical work Winslow undertakes. One deadly scene has him attempting to paint the side of the lighthouse while grimly holding onto a rope as its winched down by Wake. In another scene, Winslow lugs a heavy canister up a flight of stairs only to be told by Wake to return it. These are examples of how the film’s gritty action and the claustrophobic spaces of the lighthouse itself reinforce its bleak stylistic choices.

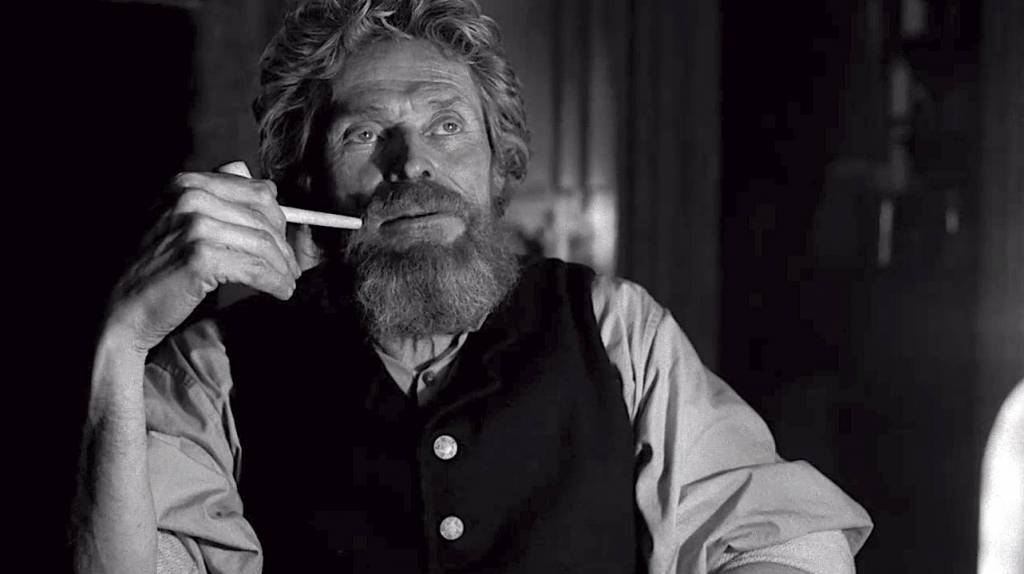

The commitment of the actors further elevates The Lighthouse. Willem Dafoe is particularly magnetic as the grizzled wickie. The actor has commented on comparisons between Wake and Captain McCallister from The Simpsons due to the way he speaks in Old English and sometimes humorously long monologues. Though one clunky idea signposted in the dialogue is that Wake might only exist inside Winslow’s head. He even refers to Wake as sounding like a parody. Does Wake symbolise how Winslow is bullying himself for what happened in Canada? Nonetheless, Dafoe thoroughly embodies the character’s scruffy appearance and his bedraggled physicality, which may have included farting on queue. Dafoe says that he cannot remember if he did it himself or if it was added in post-production, but it is still funny. As well as being highly oppressive, it is also a strong vocal performance because of the powerful monologues he recites.

At one point he humorously warns Winslow about scuffling with a seagull because it is bad luck. Robert Pattinson is appropriately submissive at the start of the film only to become more unhinged, wild, and powerful as the dynamic between the two men shifts. It is also amusing reading how difficult it was for the actors to have to consume real alcohol before filming some scenes together. There are genuinely funny moments where they gleefully drink, sing, and dance with one another. Nothing seems to unite the men more than countering their isolation and animosity with some heavy drinking. Due to their isolation, a moment of sexual convergence is teased only to become another loose idea.

The film is stylistically unique, and strongly acted but also highly elusive. Our interest in the story wavers between being a gripping power struggle and an overly ambiguous nightmare or fever dream. It never feels as tangible as The Witch. There was clarity regarding that film’s central idea about paranoia tearing a family apart. The Lighthouse also borrows a few too many devices from it too, such as the beautiful woman who becomes a deadly monster and the bizarre corruption of birds turning violent. The most confusing aspect is the ending where a key moment should provide a huge payoff. Instead, it ends on a strange note that offers few clues about what the film is trying to say.

This is before unpacking the inclusion of Greek symbolism and the film’s sexual politics. One can assume that the imagery of the gods is reflective of the deep-seated power struggle between two men vying for control over their future. The Lighthouse is also about the economic challenges faced by people of Winslow’s generation. Hard labour, gruelling task masters, and past mistakes continue to haunt you. Eggers himself has said that it is about the difficulty of confining two men together in what looks like a phallic symbol. It illustrates that conflict vividly, but a clearer allegory is lost in the deep mist. It was never going to be easy stranded in this tough, grizzly new world of nefarious seagulls and uncertainty.

Summary: It illustrates its central conflict vividly, but a clearer allegory is lost in the deep mist.