Rush – Film Review

Movie

Summary: It has the rare privilege of combining exciting Hollywood spectacle with two intimate and fascinating characters

4/5

Fascinating

Reviewed by Damien Straker on October 1st 2013

Hopscotch presents a Ron Howard film

Written by Peter Morgan

Starring Chris Hemsworth, Daniel Bruhl, Olivia Wilde and Alexandra Maria Lara

Running Time 123 minutes

Rating MA15+

Release Date October 3rd 2013

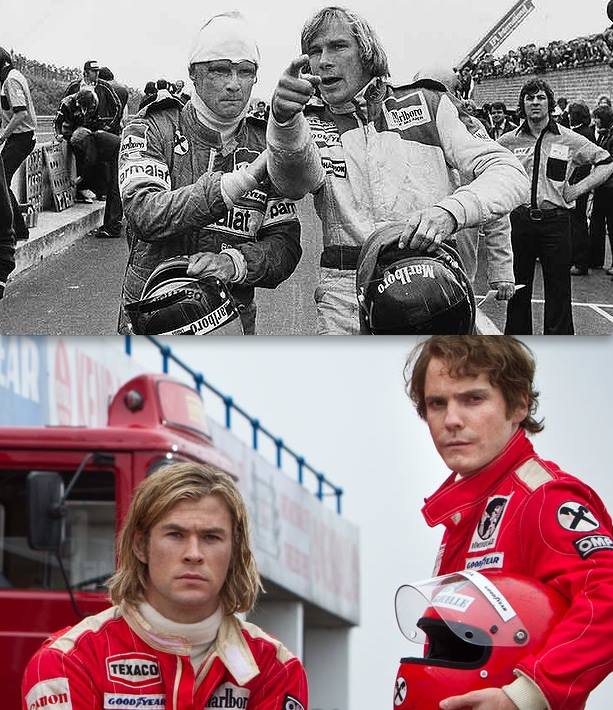

In the racing circuit of the 1970s, drivers James Hunt and Niki Lauder were the fiercest of rivals and represented the sport’s partition between glamour and science. Hunt was born in 1947 in London and Lauder was born in 1949 in Austria. Yet both men had similar economic and personal backgrounds. Hunt’s father was a successful stockbroker and Lauder was from a family of businessmen. Their families were unsupportive of their decision to shun their wealthy heritage in favour of becoming racing car drivers. Hunt at one point considered being a doctor. 1976 is remembered to be one of the most dramatic years in the Grand Prix’s history and by that point they had developed polar reputations for themselves. Hunt was a drinker, took drugs, vomited before every race and is said to have slept with over five thousand women. Alternately, Lauder was characterised as “cold, hard logic” and a technical expert on driving. He became a major advocator for driver safety in the sport.

In Ron Howard’s fictional account of this rivalry, Hunt and Lauder are played with great lucidness by Chris Hemsworth (Thor, The Avengers) and Daniel Brühl (Inglourious Basterds). We come to understand the mindsets of both men and ironically how they complimented each other. As Hunt Chris Hemsworth brims with high charisma, cockiness, wit and arrogance. He doesn’t care about others but uses them for a fleeting moment of joy or pleasure. In his first scene, he walks into a hospital bleeding with a bandage on his stomach and seduces the nurse. The danger of racing fuels this juvenile spontaneity because ‘the closeness to death’ reminds him of his own personal vitality and celebrity appeal to women. Peter Morgan’s screenplay adopts a structure similar to Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull, where sex and sport have a synonymous relationship. For Hunt, both are a moment of passion, instinct and adrenaline and sometimes inspire each other. In one sequence Hunt seduces an air hostess onboard a plane and the scene is juxtaposed against a revitalised and energised racing performance. Outside of racing and sex, Hunt is bored and directionless. His brief marriage to Suzy Miller (Olivia Wilde) is a disaster because he can’t handle a structured life. Ron Howard’s camera makes deliberate note of the image of a bird trapped in a cage. It’s an image representative of both characters because even Miller takes up with the actor Richard Burton to escape her life with Hunt.

Comparatively, Lauder doesn’t believe in popularity, partying or even friends. He is a lone wolf because it allows him to structure and discipline his life primarily around racing. Not only is Lauder unpopular with the other racers in the film, he is an outsider to his own racing team, an Austrian who is part of a major Italian racing company in Ferrari. He believes that ‘happiness is the enemy’ because when you are happy you suddenly have something to lose. His strength though comes in the form of his scientific approach to racing and his logic. He orders the material on his racing car to be changed so it runs faster and manoeuvres his way around contracts to improve his own standing with the team. Typifying his character, Hunt calls him a rat but Lauder reminds him that as disliked as they are rats are also very cunning creatures. The accident that left Lauder horribly burnt and scared on top of his head is a frightening story and powerfully handled because of the uncompromised staging. He returned to racing just six weeks later, wearing a special protective cap under his helmet to hide his burnt flesh. The physical pain is viewed in graphic detail but we also see a determination in Lauder that achieves obsessive tendencies. While having his lungs pumped, the point of view shots of the TV showing Hunt celebrating injects Lauder with unflinching tenacity and competitiveness.

If there is any disappointment with the film it is that the female partners of both men, including Lauder’s eventual wife Marlene (Alexandra Maria Lara), aren’t given proper character arcs but are moral ciphers for their domestic issues or marginalised to the sidelines. The majority of the film’s energy is spent on the racing scenes, which are an exhilarating from inside the cockpit, with cameras attached to the helmets of the actors, or over the top of the race through overhead shots. Occasionally, it is not always clear which driver is which. Pay attention to the colour of the racing cars. The most terrifying sequence in the film is when they race in terrible conditions during a downpour in Japan, forcing Lauder to reconsider his ideal that he has nothing to lose. The atmosphere in the racing scenes is heightened by an intensely desaturated colour scheme. The palettes are gritty and dark, focussing the sole primary colour red onto the racing car. This shows nothing exists outside of racing for these two men. The film is about their relationship and rivalry but also the way other people can teach us about ourselves. What they see in each other places a mirror onto themselves, reminding them of their own personal strengths. It breathes a small degree of respect between these two competitors. Hunt died at just forty-five but Lauder is still alive. He has said that he approves of the film because of its truthfulness. I haven’t watched Formula One racing before but by the end I found it difficult to look away. It has the rare privilege of combining exciting Hollywood spectacle with two intimate and fascinating characters.