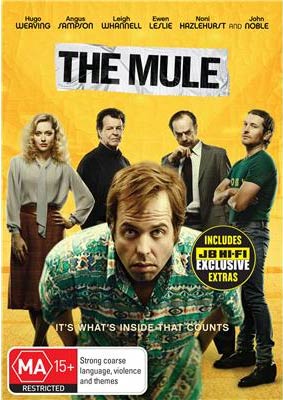

The Mule DVD Review

Summary: It doesn't integrate the humour and violence as seamlessly as Angus Sampson's other recent work like 100 Bloody Acres.

2.0

Limited

The Mule

Director – Tony Mahony & Angus Sampson

Actors – Angus Sampson/Hugo Weaving/Leigh Whannell/Ewen Leslie/Noni Hazlehurst

Film Genre – Australian Cinema

Label – Entertainment One

Audio – English (Dolby Digital 5.1)

Region Coding – 4

TV Standard – PAL

Rating – MA15+

Year of Release – 2014

Primary Format – Movies/TV – DVD

Reviewer – Damien Straker

To be a great underdog story, The Mule needed a character to admire. The best underdog stories are fables about heroes where we share their victories. Underdog stories have become synonymous with Australian cinema despite universal relevancy. One of the most popular underdog stories in Australian film history is The Castle, which celebrated the value of the home and the family unit against the government. It was Biblical, a David and Goliath story. The new Australian crime film The Mule aims, squats, lower. It’s about how long a man can contain his bowels. To be fair, it’s not the first Australia comic film to get its hands dirty. Kenny, a diamond in the roughage, was about a man who cleaned toilets to support his son. There’s plenty of clenching in The Mule, much of it intentionally painful, but unlike the aforementioned films it’s not funny. Big laughs may still not have resolved the limited story and tonal problems.

The film takes place in 1983 and parallels the America’s Cup yacht race where Australia miraculously stole a victory. During this period a sad sack named Ray (Angus Sampson) is living at home in the Melbourne suburbs with his mum Judy (Noni Hazlehurst) and stepdad John O’Hara (Geoff Morrell). Ray is named clubman of the year for his local football team and asked by his friend Gavin (Leigh Whannell) if he’ll travel with him to Bangkok. While reluctant, Ray is persuaded to smuggle a kilogram of heroin back into Australia by swallowing twenty condoms. They are bringing the drugs back for Pat Shepherd (John Noble), who not only runs the football team but is connected to Asian criminals and sends a henchman to intimidate John for his gambling debts. While trying to evade airport security with the drugs in his stomach, Ray is caught by the police and put in a hotel room. He’s overseen by two Australian Federal Police: Les Paris (Ewen Leslie) and Tom Croft (Hugo Weaving). The latter taunts and beats him for refusing to defecate. He must contain his bowels for at least seven days but risks conviction if he empties them twice in this time.

The original story was conceived by Jaime Browne after reading an article about a smuggler who refused to defecate and his own experiences of working in a printing factory where people discussed smuggling drugs. Scribed by Sampson and Leigh Whannell, the screenplay’s major plot line is a journey limited in spatiality, movement and scope. Once inside the hotel room the dramatisation of Ray’s physical endurance isn’t exactly comparable to a great piece of athleticism and his character arc is a generic transition from an immobile loser to outsmarting the police through minor sabotage of a beer bottle and television set. Other than one hangdog expression and his believable physical discomfort, Angus Sampson’s performance is muted and unassisted by flimsy characterisation. More dialogue might have helped to realise the desires and goals of his character. Attempts to mount the tension onto the physicality of his dilemma are provided by police beatings and also grotesque torture-like situations like when Ray must swallow the drugs again. Evidently, this is Whannell’s horror writer background coming to fruition, having previously written several Saw films, which also tested the pain threshold of the body.

But with contrasting authors working on the script, there’s tonal discomfort in where the film lies. First-time filmmaker Tony Mahony and his co-director Sampson have instructed the actors to rely on a deadpan and exaggerated acting style, rather than naturalism, to build the comic mood. Hugo Weaving’s over the top cop Croft and Pat’s heavy who speaks limited English are examples of caricatures employed for comedic effect. Similarly, stereotypes are another technique used for humour but the characters only possess an extra dimension because of farfetched plot twists, particularly one involving the detectives. The laughs and potential comedy are drowned out by the brutality Whannell is familiar with from the horror movies. The murders and bodies pile up outside the hotel room as a crime subplot expands the limitations of the main narrative. Along with Ray’s enormous physical pain, courtesy of the police beatings, some of the external deaths wouldn’t be out of place from a straight crime film. It doesn’t integrate the humour and violence as seamlessly as Angus Sampson’s other recent work like 100 Bloody Acres.

The time period of 1983 serves two thin purposes: referencing the underdog theme through the America’s Cup race and broad underdeveloped symmetry to the greed of the era. The major through-line is how everyone works for somebody else and driven by money. But the silent way it introduces Ray’s desires for a better life, like the small home in the suburbs and the loving mother, are cliches Australian films have relied too frequently upon rather than specifically contextual to the 80s. It is unusual to have set the film in the past when drug smuggling today, through people like Schapelle Corby, has become topical. Such indecision is echoed in the film’s lack of dramatic purpose and coda. Is its message don’t smuggle drugs? Outlast the police as long as possible? Wait for gangsters to get their comeuppance? If the reason why this film isn’t releasing at the cinema, it’s available on DVD and digital platforms only, is due to its weak message or because the film’s backers were unsure of how to market the film as a dark comedy or crime story then I sympathise with their decision.