|

In

the future, a war has left Earth divided into the United Federation of

Britain

and 'The Colony' (formerly Australia). Both the UFB and the Colony are

overpopulated and people travel between the areas through an elevator

called

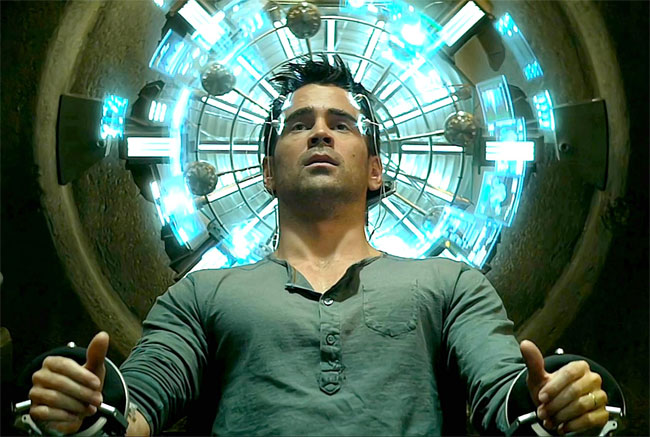

'The Fall', which transports through the core of the Earth. Douglas

Quaid

(Colin Farrell) is a factory worker who is having nightmares and finds

little

comfort from his wife Lori (Kate Beckinsale). He decides to visit a

company

called Rekall, where false adventures and memories can be implanted

into his

brain. Yet when Rekall scans Quaid to see if he is holding any secrets,

he is

accused of being a spy. Quaid manages to escape, but only after killing

several

cops. Lori turns out not to be his real wife but an agent for the UFB

who is

monitoring him. Escaping from her, Quaid is told that his name is

Hauser

and that he

has a code that could stop the evil Chancellor Vilos

Cohaagen (Bryan Cranston) but it must be shown to the resistance leader

Matthais

(Bill Nighy) first. Aiding him in finding Matthais is Melina (Jessica

Biel), a woman

from his dreams. Meanwhile, Cohaagen is blaming a terrorist attack on

rebel

fighters so that he has an excuse to use his army of robots to wipe out

people

on 'The Colony'.

Total

Recall is excruciatingly dull and

visually derivative, more intent on being a video game instead of a

film, but

unlikely to have the faintest impact on the most seasoned gamer. It is

also an

unnecessary remake of the 1990 Arnold Schwarznegger film, and another

loose and

problematic adaptation of Philip K. Dick's short story 'We Can Remember

it For

You Wholesale' (1966). The original film, which I rewatched recently,

had the

framework of a Schwarznegger vehicle, combining humour, ultra violence

and

technology. But the director Paul Verhoeven was also skilful in the way

that he

planted ideas in the audience's head about what is real and imaginary.

What was

also interesting about the original was that it predated the golden age

of

video games, but still played like an advanced version of Donkey Kong

at times.

Now that Total Recall is over twenty

years old it has been succeeded by more lavish films about memory and

dreams,

like The Matrix (1999) and Inception

(2010). On the back of the

success of Christopher Nolan's film, someone thought it would be a good

idea to

remake Total Recall for the Call of Duty generation.

That job has been

given to director Len Wiseman, whose equally tedious Underworld

(2003) series is every bit a computer game, minus the

controller. Incidentally, he has a background in developing commercials

for

companies such as Sony and Activision. And the stylistic choices he has

made

for this film show how much he is willing to pander monotonously to the

video

game demographic.

Wiseman has stated that he wanted a more grounded

approach to

the film. The sterile look of the original is replaced by grittier,

dirtier

tones of a highly industrial and mechanical landscape. This

is fine until you realise that the film's iconography is simply

derivative of

much better games and movies. The flying cars and cityscapes owe all

too much

to Blade Runner (1982) and Minority Report

(2002), while the

frequent long shots seem employed only to show off the design, echoing

the likes

of open world games such as Grand Theft

Auto. The amount of detail in the city feels wasted since it holds

no

greater stylistic meaning. Notably, there's no Mars and only a single

mutant in

this supposedly grounded take too. Instead, there are robots to be

destroyed

because they're bloodless targets (no one bleeds in movies like this

anymore do

they?) and it allows the film to steal from the recent Star

Wars prequels. But why is there such a disjunction between

games and films when they look to imitate each other? Heated debate

surrounds

whether games can be art and whether

they are becoming as sophisticated a medium as films themselves. The

technology

surrounding games continues to grow and gamers are also now encouraged

to make

moral choices that can shape the outcome of a narrative. However, part

of the

reason why Hollywood has continually failed to bridge films and games

together,

through some awful adaptations, is because games are a medium defined

by interaction. Games place a higher

emphasis on action rather than narrative

because the player has physical input,

rather than merely watching the story unfold, like a film. By their

nature, video

games are rarely allowed the time and space to develop narratives of

thematic

sophistication. They are fun and often visually imaginative but not

art. The

two mediums are simply divorced by their purpose and design, as much as

their

audience.

Total Recall

epitomises this problematic relationship. The intricate themes of

Dick's short

story, how we acquire knowledge and process information and the misuse

of

technology, are dissolved by the director's insistence on action and

designing

a video game that you can't actually play. The humourless cast, which

includes

Bill Nighy limited ridiculously to a single scene, are treated like

tokens of a

board game, moved from one set piece to another. The action sequences

they're

thrown into, which involve dodging flying cars, escaping from an

exploding lift

and jumping over rooftops, are long and boring to watch. Most

frustrating is

that there is less ambiguity here because I wasn't convinced that Quaid

was

dreaming this time. There's a scene in the original where a man in a

bowtie

provides scientific reasoning as to why Quaid is dreaming. It puts

doubt in

your mind. In this version, Quaid is told to shoot Melina and he'll

wake up. Anyone

who can believe that really is dreaming. Exit game.

|