|

Based

on the 2001 novel by Yann Martel, Life of

Pi is the metaphysical and spiritual journey of a character who

must

question their physical endurance and willingness to sustain their

faith in

God. This character is named Pi Patel and we first see him in present

day

Canada as a man (played by Irrfan Khan) who is preparing to tell an

amazing

story to a writer (Rafe Spall). Pi's story begins at a young age when

he is a

schoolboy in India. His parents are strict but intelligent and run a

zoo with a

huge array of animals. The film traces Pi's life to when he is a young

man (Suraj

Sharma), who is reluctant to join his parents once they sell the zoo

and move

overseas. Once onboard a Japanese ship transporting the zoo animals to

be sold,

a huge storm floods the vessel and Pi is separated from his family. He

finds himself

in a lifeboat with a zebra and somehow survives the storm. A fantasy

adventure

of imagination begins, where several other animals emerge from under

the covers

of the lifeboat, including a tiger. Fearful of the tiger, Pi resorts to

building himself a mini raft attached to the boat. He must use a

survival guide

and other skills to control the tiger and retake the lifeboat.

Director

Ang Lee has never made the same film twice. His constant versatility

and

creative mind for unique visual spaces defines his work. His films

including Hulk, Crouching Tiger, Hidden

Dragon and Brokeback Mountain each adopted a

unique filmic style appropriate

to the material. Only someone with such diverse and sophisticated

formal

knowledge like Lee could have made Life

of Pi work as well as it does. Once deemed unfilmable, the film's

visual

sophistication bridges the gap between an art house project and

mainstream

blockbuster. Its stunning visual qualities do not stand isolated but

provide

cinematic representations of complex philosophical questions

surrounding myths,

religion and faith.

In

lesser hands this might have been a more bloated, less intelligent

film. Before

Lee, the project was passed between several directors including

Jean-Pierre

Jeunet, Alfonso Cuaron and M. Night Shyamalan, all of whom are

considered

visual stylists. Lee's personal strength as a filmmaker is that he

rarely

allows images to be devoid of meaning. His approach to this complex

material is

wholly cinematic: he challenges the

audience to draw meaning from the properties of the screen and the

images,

realising a film that is in equal parts dazzling, thoughtful and

ambiguous.

The

only stumbling points are the early scenes where Lee deters from his

cinematic approach.

The jumble of anecdotes, including Pi being named after a swimming

pool, are

confused and estranged from the rest of the film. But the screenplay by

David

Magee finds its footing once it adopts a linear structure to tell Pi's

life

story. Expositional dialogue is skilfully masked as provocative

philosophical statements,

which are then attached to the film's Biblical imagery. The film's

midsection,

spent almost exclusively on the raft with the animals, visualises Pi's

desolated world and draws parallels to stories like Noah's Ark.

The

animals in these scenes are a powerful example of Lee's emphasis on

combing theme and image. Early in the film Pi

shows great interest in the tiger. But his father says to him: "When

you look into its eyes, you see only your own

emotions reflected back at

you". This statement is problematised by the displacement of the

animals

on the raft. Are the animals real or part of Pi's imagination? The

animals, I

think, reflect Pi's shifting emotional states. When Pi is afraid, the

tiger

shows more aggression. When he learns to tame the animal, it shows more

control. These images are also allegories for God's own existence. If

one fears

God, like Pi fears the dominance of the tiger, doesn't that project our

own

vision of God in our minds? The basis

of the film is therefore how much faith we are willing to place into

something

that might only be a state of mind.

Using a

number of aesthetic devices, the film makes a dazzling case for the

power of imagination

and visual stylisation over conventional naturalism. Colour

desaturation is

used purposely, with the white tones of Pi's clothes stressing his

desire for a

cleansing experience on the boat but perhaps also to show impending

death given

the unlikelihood of his survival. The tiger's half of the boat is

coloured red.

It matches the colour of tiger to instigate a place of fear that Pi

must

overcome. Lee also allows his camera to be unconstricted by reality.

The

fluidity and tilting movements of the camera are used to stunning

effect in a

storm sequence that takes on Biblical and apocalyptic proportions.

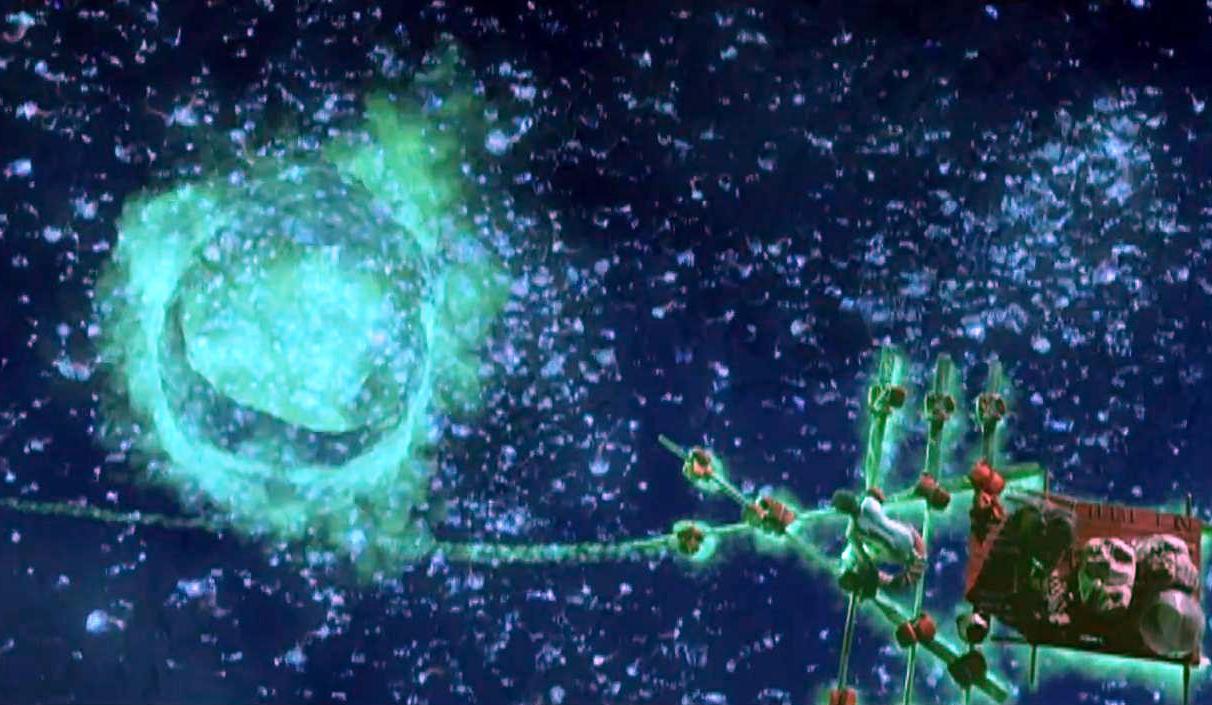

There are

gentler moments of great power too, where Lee opts to take us deep

under the

ocean, delivering some of the most striking images in cinema. Abstract

and

impressionistic images, like a sea of blue neon lights under the ocean,

are

enhanced spectacularly by bursts of colour and unintrusive 3D effects.

To define precisely

what these scenes mean, and many others including a bizarre episode

involve

thousands of fish and an island of meerkats, would be futile. The film

isn't

concerned with facts, logic or realism. It stresses how stories and

myths

inspire our survival as a species. Posing a belated question about what

type of

stories we would rather hear, inspiring fantasy or scientific rationale

like

the survival of the fittest, is clever because the answer is

predetermined by

the amazing things we've already seen. There's a small end moment where

the

film undermines its sophisticated ambiguity by explaining a twist too

neatly

but minor quibbles never deter from the power of Lee's craftsmanship.

Life of

Pi has the spectacle of a blockbuster but compliments its flair with

heart and

intelligence - compelling reasons see this astonishing film on the big

screen.

|