|

Eliezer

and Uriel

Shkolnik are locked in an unlikely father-son relationship. They are

both leading

professors within the rigorous and rarefied field of Talmudic Studies:

an obscure

discipline dedicated to the application of objective analysis to

ancient Jewish

texts in furtherance of our understanding of such topics as the texts’

historical backgrounds, reflections of daily reality, linguistic

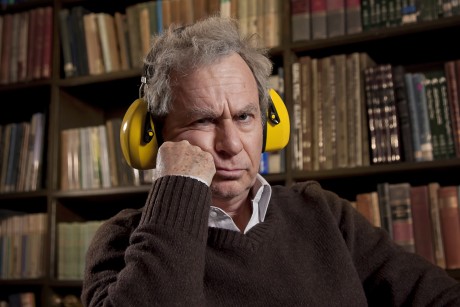

characteristics and literary sources. Eliezer (Shlomo Bar’Aba) is a

bitter old-school

purist who has spent his career parsing texts with a research-intensive

analytic

approach. His life’s greatest achievement amounts to a single footnote

buried

between the pages of an influential tome in which his legendary mentor

and the

book’s author briefly acknowledges his contributing research. His son

Uriel

(Lior Ashkenazi), by way of contrast, is a popular and accomplished

scholar who

delivers lectures in academic institutions across the country. Every

waking

moment Eliezer must suffer the ultimate humiliation of living in his

son’s shadow.

One fateful day, the Minister of Education phones Eliezer to inform him

that he

is going to be awarded the coveted Israel Prize – a personal holy grail

that

has eluded his grasp for nearly two decades. A newspaper confirms it.

Shortly

afterwards, the Israel Prize committee phones Uriel to arrange an

emergency

meeting. It informs Uriel that he is the

true recipient of the prize and that his father was mistakenly awarded

the

prize due to a freak mix-up over their identities. The sorry debacle

forces Uriel

into the dilemma of either letting his father live an illusion and

permanently

forfeiting his future claims to the award or allowing the Board to

restore

their actual judgment at the cost of his father’s heartbreak.

Joseph

Cedar’s “Footnote”

is a tragicomic triumph with a daring plotline that succeeds in the end

because

of its surprising offbeat humour and unswerving confidence in its

esoteric material.

The concept of the “footnote”, as suggested by the title, functions as

a

perfect metaphor for the film’s story and Eliezer’s character, as it is

used to

denote an anecdote that is of minor importance yet is too good to be

omitted. Cedar’s

anecdote opens up an absurd world of niche humour that mines its comedy

from

the most unexpected places. Don’t be at all surprised if you find

yourself laughing

uncontrollably at its classy collection of visual gags that image such

situations as a secret meeting held in a confined space and attended by

self-important

luminaries, Uriel serving a rocket ace in blind fury during a friendly

squash

game and Eliezer engaging in a childish argument with a guard over his

security

clearance. Cedar transforms the Israeli Talmud establishment into a

comic and

dramatic site of struggle where rival professors wage epic unspoken

wars,

highly intelligent scholars behave like little children and careers are

made or

stayed over the tiniest of details. However,

beneath all the wry humour, the story allegorises the troubling

universal relationships

between fathers and sons. The film’s comedy is thus offset by the

genuine pathos

that its familial portrayals arouse. Eliezer and Uriel, in spite of

their

respective foibles, both represent hapless victims of tragic

circumstances operating

outside their control. Bar’Aba’s

performance is outstanding in conveying this sympathetic image. The

film’s

sporadic graphic narration is tawdry, however, the film’s overwhelming

strengths

mitigate this defect completely. I strongly recommend this one.

|