|

In

1979 protests in Iran break out over the countries leadership, forcing

violent

attacks on the US embassy. Six Americans in the embassy manage to flee

and take

refuge in a house of Canadian ambassador Ken Taylor (Victor Garber).

Yet it

becomes increasingly likely that their faces are going to be recognised

and they'll

be tracked down. The CIA decides that they must come up with a plan to

try and

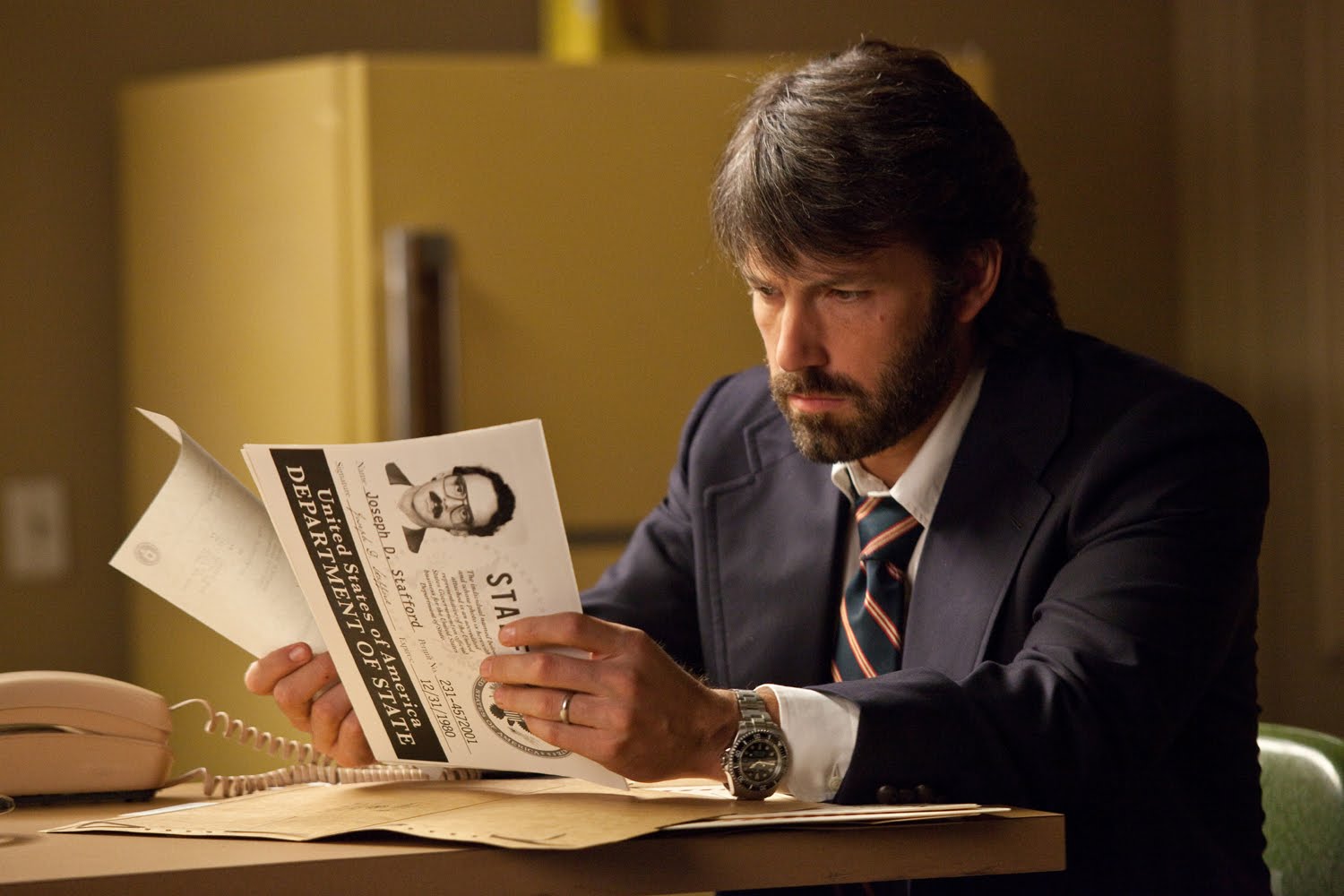

rescue these people. Enter Tony Mendez (Ben Affleck), a burnt-out agent

who is isolated

from his family, including his young son. Offset by the CIA's

incompetence,

Mendez hatches his own rescue plan: to pitch a fake movie, pretend to

shoot it

in Iran and have the six hostages pose as a film crew to transport them

secretly out of the country. He has the

support of his fellow agent Jack O'Donnell (Bryan Cranston) but needs

proper

film aid. This comes in the form of crabby film producer Lester Siegel

(Alan

Arkin) and makeup artist John Chambers (John Goodman), who supply a

script for

a science fiction film called "Argo" as their cover. Travelling into

the hostility of Iran, Mendez must convince the six embassy workers of

their

new roles and help them memorise their fake identities.

Argo is Ben

Affleck's third film as an actor turned director and arguably his most

important. The film is based on a true story, however unlikely, but

contains

uncanny modern day parallels. The recent attack on a US embassy in

Libya, for

example, is a frightening coincidence. But the movie is also founded in

a deep

political subtext about the way that global events are fictionalised

and increasingly

detached from the truth and the reality. That's what sparked the

involvement of producers George Clooney and Grant Heslov, who worked

together

on Good Night and Good Luck (2005). Clooney

is an outspoken liberal in

Hollywood and has been deeply critical of both the War on Terror and

the Bush

administration. Prior to invading Iraq, he compared the Bush government

to mobsters

from The Sopranos. But wisely, Argo doesn't

draw direct parallels to

Iraq. How could it? Instead, it's conscious of the way that political

events,

especially through cinema, are distorted

and fabricated. The film is

surprisingly self-critical in that regard, but well-equipped to pose

moral

questions that subvert the formula of its subgenre and Hollywood's

general

aversion to authenticity. The film's characters are forced to ask

whether a

plan as silly as this is an appropriate solution and whether they

should be

playing make-believe when people are being publicly strung up and

executed.

"This is the best bad idea we have", O'Donnell announces. Structurally,

the film does possess a conventional framework, with Acts 1, 2 and 3

unfolding

as you remember them, but the scenes are deliberately infused with

ongoing

sparring session between fiction and reality. Look at the opening

prologue that

summarises the political context, leading to the riots. Affleck uses

the format

of a comic book panel to outline the tension. He then intercuts between

real

footage and his own reenactment. The effect is seamless and masterfully

handled: the political back-story is recounted factually, but with

visibly

fabricated edges, only for the reality and the dramatisation to become

deliberately opaque. Problematising their inseparability, Affleck

affirms

cinemas collision with non-fiction, revealing his own film to be a highly stylised account of the crisis.

The

meta layers of Chris Terrio's excellent script also provide the most

enjoyable

and funny parts of the movie: the admission that Hollywood is a place

of huge

egos, and the bigger the lie, the bigger the profit. The humour in the

movie

scenes is set at the right pitch by experienced, charismatic actors,

especially

Arkin, who know how to control the deftness of the lines. The wit is

dry and

self-depreciating but not overly broad that it ever slips into

self-parody or

silliness. When Goodman's character is asked about a film and who the

disappointed target audience will be this time he says: "People with

eyes". And frankly, in a time where clever dialogue is being steadily

replaced by boring exposition, like in video games, isn't it refreshing

to hear

dialogue so witty that it obtains almost a lyrical quality?

Anticipating any

jarring tonal shifts, Affleck juxtaposes the mood between two

locations: we see

the silly movie costumes of a robot and a space monster contrasted

against the

Iranian household: the framing is tighter, more intensified and the

colour

filters grainier as to express the increasing tension levels. Hollywood

seems a

lot more superficial from that angle. If there are any hiccups, they

occur late

in the second half where the pacing begins to dip slightly, when Arkin

and

Goodman disappear briefly, but only for the movie to hit top flight

again with

an unbearably tense climax. The editing in this final sequence, and the

relationship between scenes, as characters rely sometimes unknowingly

on each

other and sheer luck, is handled with an astonishing level of

confidence. If

the film's structure does seem overly familiar, its rare quality is

that the

filmmakers understand that their work is a more sophisticated brand of

fiction;

compared to what really happened and how continually artificial movies

are in

relation to the real world. How often can you say that a Hollywood film

and its

director are this humble either?

|