|

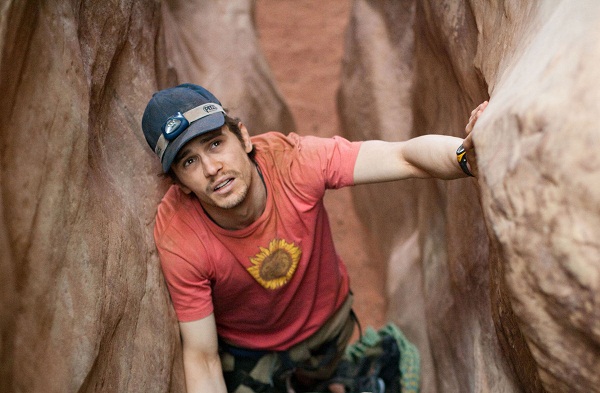

127 Hours is based on the true story of how mountain climber Aron Ralston (James Franco) was travelling across the canyons of Utah and had his arm trapped under a boulder. After being stuck for five days Ralston used little more than a blunt pocket knife to cut off his arm and escape. This film examines the ordeal as closely as possible, beginning with a zippy montage of Ralston's hectic lifestyle, followed by his meeting with two female hikers (played by Kate Mara and Amber Tamblyn), and then his drop into the canyon. From this point the film immerses the audience into Ralston's space, rapidly visualising many of his thoughts and his emotions. He remembers his family most fondly. One of the major fragments of Ralston's personality that emerges from his nightmare is a sense of regret of missed opportunities in friendships and relationships.

One of the most surprising thrillers of last year was Buried, a minor thriller set entirely inside a wooden coffin. It was an effective exercise in claustrophobia that relied heavily on coincidences. Danny Boyle's 127 Hours, adapted from Ralston's own book Between a Rock and a Hard Place, is similar in being set almost entirely in one location and with one actor on screen for much of the time. Its ambitions are however undeniably more sophisticated.

Boyle has been periodically interested in the velocity of the lives of young men, and here he uses that as a basis for an intriguing question: how will a fit, agile young man cope physically and emotionally when no longer in control of their body? He attempts to answer this using ahyper-kinetic visual style. At the beginning the thumping beats of music combine with rapid cutting and split screens to project an image of Ralston's lifestyle. He's the sort of guy thrilled to have his heart beating out of his chest. His energy is infectious to others, too. His introduction to two hikers briefly suggests that he has enough charm to still connect with people when he wants to, though after some cave diving one of the girls he meets remarks playfully: "I don't think we figured into his day".

Boyle's direction, aided by some unconventional camerawork by Slumdog Millionaire cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle, is fearless. He gives us a point-of-view from inside a water bottle so that we can see Ralston's tongue licking out the final drops from inside. He cuts to an imagining of a plentiful Gatorade container and to an extreme close-up of Ralston's face under a cloth. I have rarely warmed to this hyper brand of filmmaking as its long been used by action directors to substitute narrative for momentum, but there's feeling to Boyle's work here: he succeeds in making us feel the limitations and the desperation of this space. He achieves the realisation that every bit of water, every dropped tool and each catch of sunlight is crucial for survival.

It's a credit to Boyle and Franco that the film pulls off most of its gambles. There's a lighter scene where Ralston verbally interviews himself, like on a talk show, complete with canned laughter. It's a surprisingly funny moment but Franco's internalisation of his longing and regret is particularly notable. Ironically, the film's most touching moment - Ralston speaking into a video camera, apologising to his parents - is also its most restrained, and Franco is given the appropriate amount of time and space to bring a genuine sincerity.

Inevitably, there are some missteps with this unorthodox brand of storytelling. The flashbacks to the family are touching but they veer dangerously close to sentimentality, especially when Aron remembers his sister playing the piano with him and says hazily under his rock: "Way-to-go sis". There's also the strange recurrence of a child that is certainly not Aron's and not himself but perhaps an imagining of his own future son. Most crucial though is the absence of the aftermath. We learn that Ralston married after three years and continued with his sports (and the film ends with images of the real Ralston and his wife), but surely there were darker and more isolating aftershocks to come. Not even the fearless Danny Boyle can take us there. |