Love and Mercy – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on June 21st, 2015

Icon presents a film by Bill Pohlad

Produced by Bill Pohlad, Claire Rudnick Polstein and John Wells

Written by Michael Alan Lerner and Oren Moverman, based on Heroes and Villains by Michael Alen Lerner

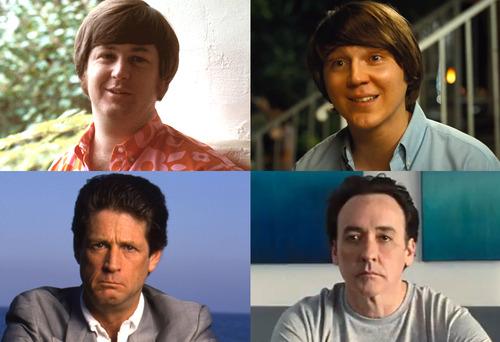

Starring John Cusack, Paul Dano, Elizabeth Banks and Paul Giamatti

Music by Atticus Ross

Cinematography Robert Yeoman

Edited by Dino Jonsäter

Rating: M

Running Time: 121 minutes

Release Date: June 25th, 2015

Love and Mercy is director Bill Pohlad’s first film in twenty-five years and he succeeds where more prolific filmmakers have failed. All cinema is about the boundaries of time and the careful selection and omission of events. It’s a challenging process given filmmakers feel obliged to be respectful of real life subjects and it’s this inclusiveness which thins out the material. This biopic of the Beach Boys singer Brian Wilson resolves the problem of chronology through two contrasting, overlapping portions of his life which become complimentary in theme and psychology. Creative authority and personal control are the film’s most reoccurring themes. The dual timelines dramatise Brian as a young man in the 1960s who at the height of his creative powers is an artistic and musical genius but also when he’s older, broken and brainwashed by his obsessive therapist. The older sequences outclass many biopics, like Clint Eastwood’s Jersey Boys, because rather than blandly laying down a succession of events the screenplay by Michael A. Lerner and Oren Moverman (the director of The Messenger) develops a compelling plot between the relationships of the characters. A quartet of impressionable performances further strengthens the film’s insights and lasting power.

In the early life of Brian Wilson, played strongly by Paul Dano (There Will Be Blood, Little Miss Sunshine), the rest of the Beach Boys are struggling to keep pace with his creative methods. Characterised with nervous, impulsive and creative energy, Brian is given permission by the other band members to produce his own music in the studio while they tour and this is where he develops the Pet Sounds album. These scenes impress by sidestepping an annoying biopic trope where a character sees an object and magically finds inspiration for their work. Instead, the film unveils Brian’s creative process, his thinking and hands-on approach as he feels his way through the music. He’s like a film director searching for perfection in his own restless mind. We see him reading and correcting the music on a sheet of paper, improvising sounds and instruments and forcing the musicians to continually play the same pieces. Despite insistence from his brothers, Brian doesn’t recycle the summer tunes of The Beach Boys’ old music and it’s this determination to test his personal creativity which places him under painful duress. He’s caught between people telling him he’s brilliant, the torment of his alcoholic father and the pressure of not stifling his own creativity. As he becomes addicted to LSD his behaviour becomes detached from reality, like hearing loud noises in his head or pausing the orchestra for hours because of bad vibrations in the studio walls. Some scenes are impressionistic like a wide angle shot of Brian sitting alone or floating around in the pool underwater. Their duration can feel long, slow and detached but this highlights his drug fuelled state.

The cuts to the 1980s are the best portion of the film and its impact is felt as it becomes a subversive fairytale. John Cusack plays the older Brian, now worn-down and drained of creativity and imprisoned inside a castle taking the form of a sterilized beach house. His rescuer is former model turned car saleswoman Melinda Ledbetter (Elizabeth Banks), until their romance is sabotaged by Dr. Eugene Landy (Paul Giamatti), who has diagnosed Brian with schizophrenia and further embodies the theme of control. This triangle builds an effective contrast of sweetness, comedy and psycho terror. Landy is a twisted parental figure and an irredeemable monster. He deliberately over-medicates Brian to subdue him and surveillances his romance like a stalker by constantly policing their behaviour and demanding to know the details of their lives. He tries justifying his methods to Melinda by describing Brian as “a boy in a man’s body”. While in the film Landy seems heavy-handed or one dimensional, the characterisation is accurately portrayed. Landy did shut people out of Brian Wilson’s life for years and held him like a prisoner to embed himself into his music career.

However, the film has an external view of his character. The money which drove Landy and why he dug into the music side isn’t highlighted and this clouds his motivations. The performances in this timeline still impress, including a career highpoint for John Cusack. Subdued by a cocktail of drugs, he plays Brian with an introverted physicality, like he’s trapped or sunken inside his own body. He also tempers the performance with humour, discovering a harmless and awkward man who nonchalantly reveals his most painful memories to Melinda over dinner, including his isolation from his daughters and his abusive father. Cusack’s likable innocence and deadpan persona is matched perfectly by the warmth, beauty and expressiveness of Elizabeth Banks (who recently directed Pitch Perfect 2). It’s a significant part for the actress, defined by a series of large and subtle facial expressions which envision her sadness and empathy for Brian. Paul Giamatti is also powerful, giving perhaps his most unlikable and uncharacteristically mean-spirited performances and while the brutality of the portrayal is thick it is by most accounts a truthful interpretation of Landy.

Love and Mercy is about the battle between creativity and control and contrasting wills. In both sides of the story Brian Wilson is never free. He’s a prisoner of his own determination to remain original in his work, despite the antagonism of his own family members, and in his later life he’s a physical prisoner given Landy overtakes his career, his body and his mind. The structure of this film, cutting back and forth between Brian’s youth and his helplessness, sometimes makes us impatient for the best parts but it builds a larger portrait of its subject’s psychology and experiences rather than a linear trajectory of his life events. Both sides of the film are complimentary in theme and impress for different reasons. It’s the John Cusack side which elevates the film and it’s the one I was most interested in seeing. The quality of the performances in this section leaves an enormous imprint over this already impressive biopic.

Summary: A quartet of impressionable performances strengthens the film's insights and lasting power.