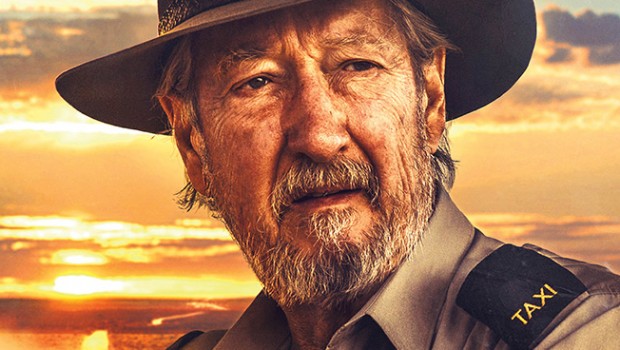

Last Cab to Darwin – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on July 30th, 2015

Icon Film Distribution presents a film by Jeremy Sims

Producers: Greg Duffy, Jeremy Sims, Lisa Duff

Starring: Michael Caton, Ningali Lawford-Wolf, Mark Coles Smith, Emma Hamilton, John Howard, David Field, Alan Dukes and Jacki Weaver

Written by: Jeremy Sims and Reg Cribb

Cinematography: Steve Arnold

Music by Ed Kuepper

Edited by: Marcus D’Arcy

Running Time: 123 mins

Rating: M

Release Date: August 6th, 2015

The Australian drama Last Cab to Darwin telegraphs a pivotal moral decision in its narrative so prematurely it leaves little doubt over the film’s resolution and identity. Disappointingly, this is a lightweight road trip movie, which takes few chances, provokes no debate and hand-holds us through a long narrative whose supposedly profound message is synonymous with American feel-good movies: that life is worth living and people can change. Aside from some pleasant humour and a promising first quarter, it becomes boring and unsurprising. The film’s safety is at odds with its central issue of euthanasia, a sensitive moral and political topic, and one which should have generated extensive discourse beyond familiar arguments like whether the sick should determine when they’re allowed to die. This is not a new debate or question and the way the film discards a new angle or insight in favour of clichés and a soft commercial approach, including a happy ending, is a cop-out and a wasted opportunity.

The director Jeremy Sims (Beneath Hill 60), who co-wrote the script with Reg Cribb the writer of the 2003 stage play, says the film isn’t about euthanasia and he wasn’t interested in making an issue-based film. Why include a divisive, timely and political issue if you’re unwilling to approach it? The content of the narrative, including a climatic decision, ultimately debunks Sims’ supposedly apolitical views, and reveals the film’s conservative ideological standpoint. By employing safe choices and resolutions for the characters, the film panders to audiences claiming Australian films are overly dark or depressing. Darwin is not only compromised and needlessly long but politically timid. The conservative view is hidden beneath a feel-good story, meaning it isn’t liberal enough in its ideological goals or themes to challenge its subject and audience.

Michael Caton stars as Rex, a Broken Hill taxi driver with little meaning in his life aside from his pet dog named Dog. He also sleeps casually with his neighbour Polly (Ningali Lawford-Wolf) and drunkenly stumbles his way home from the pub of an evening. His friends (John Howard, David Field and Alan Dukes) are usually drunk, telling bad jokes or hoping Rex will pay for their drinks. Rex is also told by his doctor they weren’t unable to remove all of the cancer inside him and he has three months to live. In the first of several coincidences, Dr Nicole Farmer (Jacki Weaver) is settled in the Northern Territory and pushing headlines about euthanising patients by showcasing a new electronic device she uses for the procedure. Believing he has nothing to lose, Rex ends his fling with Polly and decides he’ll drive 3000km to Farmer in the Northern Territory. Will Rex use her method or have a change of heart? The choice becomes too predictable after Rex tells a story about what his father did for his family.

Long before that pivotal choice is made, Darwin’s pro-life ideology is embedded into the character arcs and conventional narrative developments to justify the conservative political stance. The narrative is like many road trip movies derivative of Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957), minus the sophistication or complexity, where an old man at the end of his life influences the young people around him. But Rex’s relationships are based on wish-fulfillment and favour sentimentality rather than employing tension, conflict and obstacles that can raise the tension levels. He meets a comic relief character in Tilly (a wildly charismatic Mark Coles Smith), a young Indigenous man who was going to be a footballer with the Essendon AFL football club but opted to stay with his young family. The extent of the racism Tilly feels in the outback is limited largely to not being allowed into certain pubs.

Tilly’s problems are treated as loosely structured episodes, like trying to steal Rex’s wallet, and briefly slipping back into alcoholism, which over-simplifies their seriousness and resolutions. Rex and Tilly mutually agree not to run each other’s lives, but they’re not fooling anyone. Rex encourages Tilly to join a football team and reach his potential and Tilly and his wife mirror Rex’s relationship with Polly, which upholds the simplistic idea of life being worthy in the company of others. While Sims argues for the film’s objective approach, the narrative’s idea of life and living is purposely juxtaposed against the dilemma of euthanasia and unquestionably influences its resolution. The movie is too polite to be interesting and it’s objectionable how the film uses such simple-minded philosophy and clichés, reflective of feel-good movie formulas not real life, to make a political statement against euthanasia.

Political ideologies aside, too much of Darwin is implausible and contrived. Rex and Tilly meet an angelic barmaid from London named Julie (Emma Hamilton), who would you know it, studied medicine for four years. Even after Rex tells Julie that Tilly is married it’s completely superfluous and doesn’t build any conflict between them. When she inevitably becomes Rex’s nurse, the film resorts to montages of them watching the sun together, holding hands and buying clothes like a father and daughter. Isn’t that heart-warming? But the context of her character and why she’s in Australia is vague, particularly when she says: “I just wanted to see the sun”. There’s also awkwardness about the handling of Jacki Weaver’s scenes. Farmer lets Rex, a patient she’s just met for the first time, stay at her house and a potential thread of conflict between herself and Julie over whose taking ownership of Rex dissipates too quickly. A television screen showing her demonstrating her death machine on an obnoxious morning show program is also a bizarre and unnecessary attempt at comedy. Furthermore, the film has serious lapses in realism and medical credibility, including poor hospital security and a miraculous recovery: Rex is near death but in the next sequence he’s capable of driving long distances alone.

In the end relationships are calmly resolved, Rex’s once useless friends prove their worth and it closes with the sun fading down. It’s a film which believes how bright and sunny life can be for people by cleanly resolving their social and personal issues. But Last Cab to Darwin isn’t real life at all or offering sophisticated arguments to justify its conservative stance against euthanasia. It’s recycling boring, safe movie formulas, where a person’s suffering and social problems are neatly resolved in the company of others. It is dumbfounding how simplified the central political issue of euthanasia becomes when supported by cliché formulas. Did it really need two hours to reach its dull life-affirming theories? Mainstream Hollywood has proven it’s capable of approaching taboo social issues, with Clint Eastwood’s Million Dollar Baby (2004) offering an unflinching look at euthanasia. Unlike Hollywood, the Australian film industry is supposed to be less filtered and not determined by people who believe dark subject matters are too risky for commercial success. And truthfully, when there’s talent like Michael Caton and Jacki Weaver involved why would you waste that opportunity by taking the safest route possible?

Summary: Darwin is not only compromised and needlessly long but politically timid.