DVD EXCLUSIVE 1:1

INTERVIEW WITH

JAMES GAY-REES

(PRODUCER)

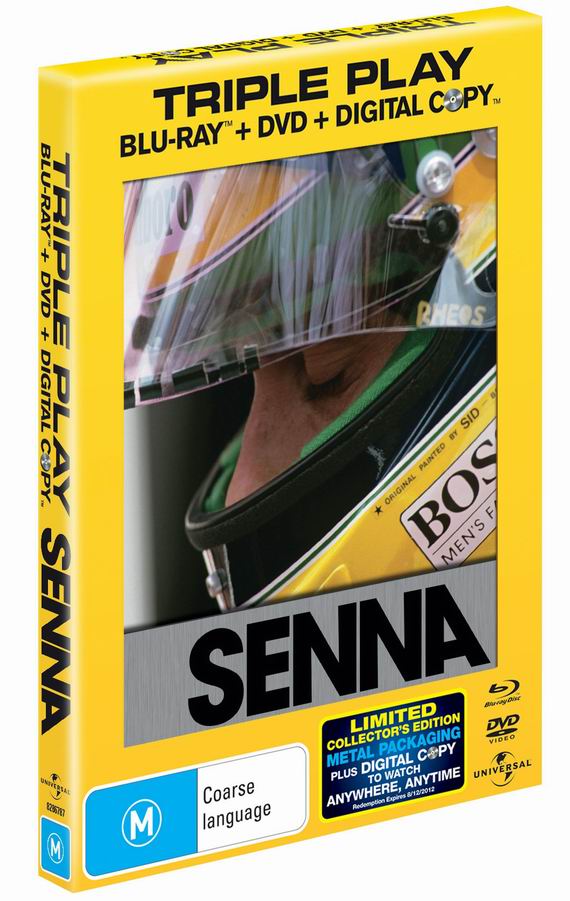

Filmmaker James Gay-Rees worked as a producer on the

likes of Long Time Dead, Blackball and Allegiance

and recently produced Exit Through the Gift Shop, the

directing debut of Łber-cool graffiti-artist Banksy. His latest

offering, Senna, which he produced with Manish Pandey and

directed by Asif Kapadia, is a stunning documentary that

explores the extreme dedication displayed by arguably the

worldís greatest-ever Formula One driver, Ayrton Senna. Charting

the Brazilianís rise to become a triple World Champion, against

the odds, before his tragic death at the 1994 San Marino Grand

Prix, which rocked the F1 world. The film won the 2011 World

Cinema Documentary Audience Award at this yearís Sundance

FestivalÖ

How was the recent Brazilian premiere? Ayrton Senna means so

much to people over thereÖ

It was quite daunting; they find it really hard. Obviously the

Brazilians find it tough because it represents such a different

time for them now. They are on such a high now. The economy is

booming. They have the Olympics and the World Cup coming up,

whereas while Senna was alive it was a much darker period for

the country. He was the only thing they really had to get

excited about and then he dies, of course. So it was a bit of a

tough watch. The reviews were really good.

And the Sundance audience responded to the film, which is great

because F1 means nothing in the USAÖ

They really connected to the character. It was really

interesting. Partly what it is, I think, is that he is young,

good looking, talented, ambitious and a God-fearing guy ó an all

American kid, in a way. He looks the part and I think that is

why they responded to him. And thatís very important for us;

that it does so clearly connect with a broad audience, not just

an F1 audience which is obvious. F1 fans will go and see it but

we know for a fact, without a doubt, that the film just works as

a movie for people with no connection to F1 at all.

Your father worked with Senna during the 1980s, on the Lotus

team, right?

Thatís right. Ayrton was driving for Lotus in 1985-6 and my dad

was the account rep for John Player Special. He was an

advertising guy and they sponsored the car. After a Grand Prix

my dad would do a photographic campaign with Ayrton, get a

photographer and create something. He said there was one amazing

time when there was this quite famous photographer and they were

in Imola funnily enough (where Senna eventually died

unfortunately), and they were literally standing in the middle

of the straight with this huge camera on a tripod and there was

this black dot at the other end of the bit of track. Effectively

he was coming towards them in the car and just peeling past them

at a 180mph. Today, Health & Safety would never let you do that.

He said it was one of the most unnerving experiences he has ever

had because they had to do that about 15 times with this car

coming like a bullet towards him.

Did your dad know other drivers, too?

My dad became very good friends with one of Ayrtonís team mates

at Lotus, a guy called Eddie DeAngelis, who subsequently died in

testing a couple of years after Senna. He was the opposite of

Senna. He was an incredibly sophisticated Italian count, a real

aristocratic playboy driver, supper with champagne and all that

sort of thing.

What did your dad tell you about Senna?

What he was always used to say about Ayrton was that he was a

fantastically good driver and had something extra special about

him, skill wise, but what really lodged with my father was that

he had this spiritual intensity. He was a very intense, very

focussed, very ambitious young guy and he seemed much older than

his years. All the other young drivers of his age group were

getting their leg-over as much as possible, having fun in the

paddock and even though he enjoyed that side of life, he was

clearly happiest to be on his path, to get to where he really

wanted to go to as quickly as possible. That struck my dad.

Ayrton was only 24 or 25 which then was very young for a F1

driver, although not so much any more. He kept on saying this

guy has something about him: ĎHe is so different. I canít put my

finger on it. He is not like the other kids.í

Is that where your interest in F1 stems from?

I am not a massive F1 fan. I am quite good now. I have become

much more interested since we have made the movie. For me I had

an interest in, and a preconception of Senna due to what I had

heard from my father. I was then keen to add layers to that and

build that up. He did not disappoint as a character and when we

peeled off the layers he was even more extraordinary. I did

think he was a fairly exceptional character. He is not perfect.

He is very flawed in lots of ways. But he is pretty imposing and

such an intense character. There was a real contrast between him

and say, Eddie DeAngelis. So that was the connection. As a young

kid, 15 at the time, hearing my dad talk, these things just

lodged in my memory and stayed with me.

The film touches upon, but does not dwell on, Sennaís personal

life. Is that because itís extraneous to your story, or was

there a lack of footage, or maybe you didnít want to upset the

family?

I think that it was a combination of all those things. But yes,

we were trying to explain with the film what it took in order

for this guy to get where he wanted, in order to become the

worldís best driver. Basically he had to go on this mad journey,

so what price did he pay? What did he have to do in order to

achieve that; not just in technical racing terms but in terms of

the politics of the sport? What were the obstacles and how did

he overcome them? What did it take out of him? What did he use

to motivate himself to go to this extraordinary place? I donít

think his relationships throughout that ten-year period were a

key factor in that singular vision. I donít think he is

concerned with keeping his girlfriend happy, because he was on a

solo journey. Obviously, he had lots of different relationships

and I am sure that those women could have shed light on him

being on that journey but we did make the decision then that if

we did speak to one we had to speak to all of them and there

just wasnít room in the movie.

What was the familyís reaction to the finished film?

Bianca Senna, Ayrtonís niece, who has become a very good friend

of ours now, was our contact on their side of things. She is

about our age and she gets the process, understands what we are

trying to do. She saw a couple of rough cuts and gave us her

notes, which were really helpful. Then we finally showed it to

the whole lot, to Viviane (Ayrtonís sister), his mum and Bianca,

and she brought a huge bunch of people along to Cannes. We

screened it for them during the festival basically. They got

it.

What feedback did they give you?

The thing that Viviane said and she said a lot about this at the

press conferences in Brazil, was that she really liked the way

we handled his fight against the politics of the sport. She felt

quite strongly that he wasnít treated fairly. It was pretty

evident in the film. He was always up against it. He was always

on the outside even though he was triple World Champion. He

didnít have an easy ride. He wasnít very good at the politics

game like Alain Prost was. He knew he was being turned over. And

he was. They were definitely taking the piss a few times.

One of the filmís great successes is the lack of Ďtalking

headsí. The only visuals are footage, which is most unusual in a

documentary filmÖ

It was Asif who basically said that we have such a wealth of

material, maybe we can do this in a non-traditional way, without

talking heads. That is the obvious way to do it but we had so

much great material we thought: letís do it without that. And I

was all for it. Nobody has really done it properly before and I

thought it would be remarkable. If we could do that we donít

ever break the moment on screen and it would seem much more like

a movie. And thatís been the overwhelming response to the film;

it feels like a movie because you donít go backwards and

forwards.

Asif Kapadia has proved an inspired choice as director, but why

did you think he was the man for the job to begin with?

We interviewed a variety of people and the reason we ended up

with Asif is because Manish and I loved The Warrior; it

is so visual. And Senna was the warrior, so there were lots of

relevant ideas contained in that. Asif has a great

photographerís eye, too and when you have such a vast amount of

archive you do need someone who can quickly say, ĎThatís a great

image and thatís a great image.í That was a big part of it.

There are a few feature films in development with racing as a

backdrop, but theyíve not proved too successful in the past. Do

you have any thoughts as to why?

There are few classic ones, [1971 documentary] Le Mans,

and a couple of others but there hasnít been one recently. I

think itís because it is really hard to replicate the

authenticity of it. Take the Micky Ward boxing movie, The

Fighter, for example and that is two guys in a ring. But if

you are trying to replicate the spectacle of the F1 environment,

thatís tough. And when you get under the skin of Senna to see

what it actually does take to be that good at something, it is

very hard to imagine. I think our film shows just how hard it is

and just how special Ayrton Senna really was.