Interstellar – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on November 4th, 2014

Roadshow Films presents a film by Christopher Nolan

Written by Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan

Produced by Emma Thomas, Christopher Nolan and Lynda Obst

Starring: Matthew McConaughey, Anne Hathaway, Jessica Chastain and Michael Caine

Music by Hans Zimmer

Cinematography: Hoyte van Hoytema

Edited by Lee Smith

Running Time: 170 minutes

Rating: M

Release Date: November 6th, 2014

Amidst the stars in the galaxy known as Hollywood a deep mystery remains: who is Christopher Nolan as a filmmaker? After seeing Interstellar in IMAX, his ninth and least satisfying film, the question perpetuates. Nolan is one of the most powerful and bankable directors in the world. Together, his last four films earned nearly four billion dollars. Money builds opportunities and egos in Hollywood and consequently each entry in Nolan’s filmography has grown in size and scope. Yet outside of his admiration for 35 mm film and practical effects, grasping Nolan’s auteurist imprint is difficult. He says he wants to make the biggest film possible but so does Michael Bay. Nolan’s films walk a difficult line, balancing large ideas and explosions, proving blockbusters don’t have to be mindless. But these are studio films, without insight into the filmmaker himself like transparent ideological goals. In interviews, Nolan mirrors this impersonal nature. He is softly spoken, measured and serious, concurrent with the thematic goals of his films like the hidden identities of men.

In 2010 The Guardian asked if Nolan is the new Stanley Kubrick, a misguided comparison with superficial parallels. Kubrick distanced himself from Hollywood by owning his own cameras and editing equipment. He also relied on the specificity of images to create meaning rather than dialogue, making his films cinematic in form, not merely scope. Stylistically Terrence Malick (The Tree of Life) is a more appropriate companion to Kubrick. Artistically, Nolan shares more in common with Steven Spielberg as both directors inject ideas into the existing framework of sizable studio films. Spielberg was originally hired to direct Interstellar with Nolan’s brother Jonathan writing the script from an idea by physicist Kip Thorne. Christopher Nolan replaced Spielberg and helped rewrite his brother’s script. The first hour of Jonathan’s original script was set on Earth and retained but his brother’s decision to refine the space elements has drawn comparisons to Kubrick’s flawed masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey and Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

To this point, I have enjoyed many of Nolan’s films but Interstellar’s script is terribly inconsistent. Using a mostly narrow, linear structure, the narrative hurls ideas at us about climate change, parenting, space exploration, time travel and alternate dimensions, but the script lacks refinement. The Nolans talk over us, not to us. In a self-conscious move to intellectualise a “save the world” story, they substitute detailed characterisation and backstory in favour of impenetrable scientific discussions about relativity and gravity. An embarrassingly rich cast is left to substantiate these thinly realised characters. Cooper, played by Matthew McConaughey, is a former pilot who is now a widowed farmer with two young children, including a girl named Murph (Mackenzie Foy) and an ageing father-in-law (John Lithgow).

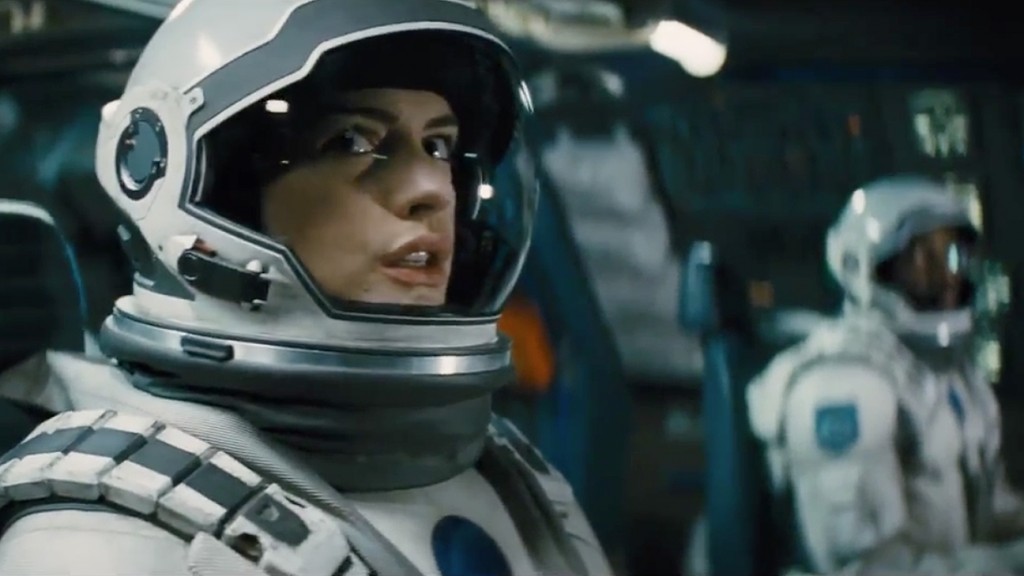

Cooper, not dissimilar to Richard Dreyfuss in Close Encounters, is an archetype of the reckless parent who is sentimentally motivated by his children and largely only interesting because of McConaughey’s predictable charisma. Earth is doomed because of dust storm and droughts, a nod to The Grapes of Wrath, leading Cooper to be tasked by Professor Brand (Michael Caine) with travelling into space and investigating three potentially inhabitable planets. Another major character is Brand’s astronaut daughter Amelia (surely named after Amelia Earhart), played by Anne Hathaway. Her reliable expressiveness instills some surface emotions to an otherwise stony character, with no backstory or arc. Other actors are either underused or have distracting cameos. An actress the quality of Jessica Chastain deserved a bigger part but only features deep into the story in a forgettable role as the adult Murph.

This time the self-seriousness which gave the Batman films a unique stylistic tone is Nolan’s Achilles’ heel. While desperate for the story to emotionally resonate, resorting to extended close-ups of Cooper crying for leaving his children behind, he remains unaware of the story’s absurdity. It is an insurmountable task when the dialogue is dry, textbook theory and the plotting becomes increasingly ridiculous, attempting to marry between the spaces of a bookcase shelf the pretentions of alternate dimensions with a family melodrama. There are also episodes where the stock characters fail to move us. During the exploration of the first planet a side character is killed, which expectedly strikes a chord with Cooper and Amelia, but matters little to us when we’ve barely come to know the character’s name. Other singular moments remind us of how skilful Nolan is with set pieces. The first entry into outer space is intensely realised, with the galaxy being simultaneously beautiful and dangerous. The infrequency of these emotions stresses how undisciplined the narrative is, particularly in an incoherent, final hour, which doesn’t utilise the multilayered structure of The Dark Knight Rises or strike Inception’s emotional high notes.

Watching the film in the IMAX format is as inconsistent as the narrative. Hoyte van Hoytema, the usually reliable Dutch-Swedish photographer who shot Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, Her and Let the Right One In with great symmetry, has replaced Nolan’s regular photographer Wally Pfister. Surprisingly, the early scenes on Cooper’s farmhouse are poorly lit and the images are muddy and graining, a deliberate imitation of the sandstorms, but an ugly choice all the same. Other shots use the full volume of the IMAX screen and the scale is impressive. Some of the galactic images are awe-inspiring and vivid but their scarcity coupled with the tight, obstructed camerawork inside the spacecraft, is disappointing. Uncharacteristically, Nolan’s pacing is also laborious, dragging the film to his longest running time of nearly three hours. The film isn’t as calculated as 2001, a difficult feat for any director, but pales substantially to last year’s terrific Alfonso Cuaron film Gravity, which eclipses Interstellar for precision. It was made for sixty-five million dollars less. It is half the length and aside from being a technically superior film, it understands the futility of a large canvas unless our emotional investment is supported by strong characters. Many promising filmmakers have at some point in their career been swept away by the Hollywood black hole. Nolan is intelligent and will recover before then but might benefit from making smaller films which can still support some of his bigger ideas.

Summary: To this point, I have enjoyed many of Nolan's films but Interstellar's script is terribly inconsistent.