High Ground – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on the 23rd of January 2021

Madman presents a film by Stephen Maxwell Johnson

Produced by David Jowsey, Maggie Miles, Witiyana Marika, Greer Simpkin, and Stephen Maxwell Johnson

Screenplay by Chris Anastassiades

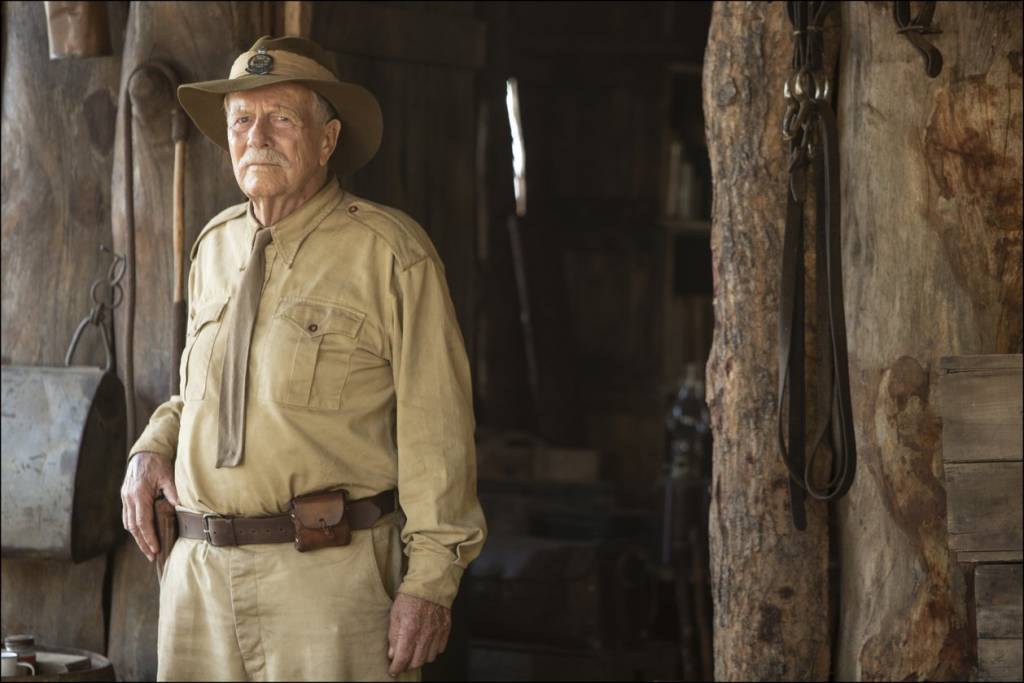

Starring Jacob Junior Nayinggul, Simon Baker, Jack Thompson, Callan Mulvey, Aaron Pedersen, Ryan Corr, Caren Pistorius, Sean Mununggurr, and Guruwuk Mununggurr

Cinematography Andrew Commis

Edited by Jill Bilcock, Karryn De Cinque, and Hayley Miro Browne

Rating: MA15+

Running Time: 104 minutes

Release Date: the 28th of January 2021

Despite a strong, authentic depiction of Indigenous culture, High Ground leaves us longing for a more nuanced thriller. The Australian drama marks the second film by filmmaker Stephen Johnson in twenty years. Outside of his television work, his previous feature was the Indigenous coming of age story Yolngu Boy (2001).

The well‑received drama was the first film to be shot in Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory with a full Indigenous cast. Its authenticity elicited from Johnson’s upbringing in the region. He was born in London and lived as a child in the Bahamas and Africa before his family moved to Australia in the 1970s.

While his father taught Indigenous students, Johnson himself forged strong connections with the Bininj and the Yolngu people. Consequently, he has returned to Western Arnhem Land with this new Indigenous Western. It was filmed in the Kakadu National Park. Johnson’s understanding of the land and its people is attributable to why its depiction of a violent massacre of Indigenous Australians is realistic, direct, and upsetting.

While the brutality is painfully honest, Johnson has conceded High Ground is fictional. He also intended for it to be an entertaining film. The cultural depiction is undeniably meticulous, but as a character study its script lacks polish and depth. It is confined to the expectations and cliches associated with an Australian Western.

The bleak outback story opens in 1919 and veers thematically between strained loyalties and violent retaliations. As a young Indigenous boy, Gutjuk (Guruwuk Mununggurr) wants to be a hunter and is beginning to learn different survival skills. Meanwhile, a group of white Australians aim to arrest an Indigenous man for killing a cow. The conflict erupts into a terrible massacre where an entire Indigenous village is murdered by the men.

One man who reacts differently is a former World War I soldier, Travis (Simon Baker). He quickly shoots some of his fellow soldiers for their unforgivable crimes. One man he is unable to kill in time is a racist soldier named Eddy (Callan Mulvey). Together, they discover Gutjuk hiding in the reeds but choose to set him free.

The story forwards twelve years. In the 1930s, Gutjuk (now played by debut actor Jacob Junior Nayinggul) works on a farm and Travis is assigned a mission from his commander, Moran (Jack Thompson). He is ordered to capture Baywara (Sean Mununggurr), Gutjuk’s uncle. Baywara’s people were murdered in the village and now he is burning down farms.

Travis enlists Gutjuk’s help to find his uncle but is asked whether Baywara will die once located. Travis is also urged by a priest, Braddock (Ryan Corr), and his sister, Claire (Caren Pistorius), to protect Gutjuk. The urgency to locate Baywara rises upon the return of Eddy. He is now intent on finishing the job but this time he is accompanied by his own Indigenous tracker, Walter (Aaron Pedersen).

High Ground’s technical aspects, including its lush photography and impeccable sound and costume design, evoke a superb realisation of Indigenous culture. The years Johnson spent bonding with various Indigenous communities are apparent in his stylistic choices. By opting to shoot in the narrow 1.85 ratio and filming using wide angles and close-ups, he captures the outback’s scorching climate and the specificity of nature itself.

A powerful early image is a raging fire at night as Baywara burns a property to the ground. The black and red colours meld together into a brief but palpable display of bleak hellfire. Images like this reflect the film’s title, which infers viewing the destruction of the land from afar but gaining perspective of the chaos. One visual misstep is Johnson’s overreliance on cuts to overhead drone shots to impose top-down views of the rich countryside.

Fortunately, the technique does not undermine the gentle naturalism, such as rockfaces and a shallow creek where Gutjuk hides under the water. Johnson’s camera also tightens as a bird calmly perches on a rock and then spies a crocodile being pulled out of the water with ropes. The Indigenous facets are acutely handled too, including warpaint drawn across Gutjuk’s dark skin and the authentic Indigenous costumes by Erin Roche. The sound design, including the Indigenous singing and native dialects, further amplifies the solid attention to detail.

Less assured than Johnson’s technical choices is the screenplay by experienced television writer Chris Anastassiades. The reliance on Western cliches over strong fundamentals is transparent and forwarding the story twelve years is an unnecessary complication. Following the heinous inciting incident, it dilutes the exposition’s flow and urgency. Furthermore, High Ground is uncertain and disjointed regarding its central protagonist.

The film could have adopted one clear perspective, where a young Indigenous man shifts from adolescence to making difficult choices as an adult. Instead, it wavers between Gutjuk’s fear of betrayal and cutting to Travis’ dilemma. He is a quietly stoic white male who teaches Gutjuk to shoot and faces uncertainty about his allegiances. The gap between the protagonists widens when the men become physically divided late in the piece. Here the story’s controlling idea also moves from exploring fractured loyalties to underlining violent retaliations.

These flaws would be less notable if High Ground’s characters transcended their stereotypical form. Its references to the First World War are apt. The honourable war veteran, the pompous senior commander, the racist villain, a sad but ineffective priest, and a young soldier yet to see action would not be misplaced in a B-grade war film. Fewer characters but ones richer in backstory would have been preferable to using underwritten archetypes.

Jennifer Kent’s colonialist thriller The Nightingale (2018) effectively subverted the overused tropes of the outback genre. Rather than focusing singularly on battle-hardened men, she examined the bond between a young woman and an Indigenous man as a powerful metaphor for consent. High Ground’s narrative choices are comparatively predictable. As if constrained by its budget, it is determined to resist distinction from countless outback features depicting the bloodshed between Indigenous people and violent colonialists.

Some of the script problems filter into the performances of the otherwise gifted ensemble. A stronger backstory for Travis besides being a WWI veteran would have been preferable. Still, Simon Baker successfully humanises him as visibly troubled by the violence and the dilemma surrounding his loyalties. He faces the impossibility of being honourable in a lawless world where bloodshed is inevitable.

If this character were secondary to Gutjuk it would have provided Jacob Junior Nayinggul with more time to explore his character’s personality and goals. The screenplay could have adopted his perspective first as an Indigenous fellow pressured to betray a family member or act bravely against racist white men.

Jack Thompson draws from his years of experience to characterise Moran as an enjoyably pompous commander. He says to Travis: ‘you know how civilisation is built? Bad men doing bad things’. The line stresses the inevitability of immoral behaviour. He is guided by optics, staging photos with Indigenous people to inflate his control over the land. The other side characters are less detailed. Ryan Corr’s role as the priest fizzles. Despite an early crying scene, the character’s purpose dissipates. It is a waste of the young actor’s incredible versatility.

Though predictably sidelined, Caren Pistorius reinforces her character’s protectiveness and has more agency in the climax than expected. Callan Mulvey ensures Eddy is appropriately slimy, but there is limited room to add nuance and complexity. Aside from a suggestion he killed few people as a spotter, he is a one-dimensional villain. Aaron Pederson’s part is meagre and an injustice to this actor’s presence. Despite the uneven material, there are undoubtedly affecting moments, particularly when an Indigenous man weeps over the bodies of his fallen people.

High Ground will inevitably draw conflicting reactions from its audience because of its execution and troubling subject matter. It is, as it should be, confronting viewing. The graphic violence will deter some and limit its broad commercial appeal. Yet the brutality amplifies the realism and the verisimilitude of Stephen Johnson’s creative efforts. The film’s massacre is fictional but born from stories passed down that illustrate the senseless crimes committed against Indigenous Australians as we pillaged and murdered across their land.

The technical elements are praiseworthy and add heft to story’s confrontations and aesthetics. However, when judged solely as entertainment, High Ground is not a consistently satisfying thriller. The writing and characterisations are flimsy, and some high-profile actors are underused. The story’s tension lingers more on the predictability of its brutal violence than admiration for the characters. Yet now that he has returned to filmmaking after a long absence, one hopes Stephen Johnson’s future Indigenous films offer as much finesse in the writing as his otherwise solid direction.

Summary: Despite a strong, authentic depiction of Indigenous culture, High Ground leaves us longing for a more nuanced thriller.