Hell or High Water – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on the 20th of October 2016

Madman presents a film by David Mackenzie

Produced by Sidney Kimmel, Peter Berg, Carla Hacken, Julie Yorn, Gigi Pritzker and Rachel Shane

Written by Taylor Sheridan

Starring Jeff Bridges, Chris Pine, Ben Foster and Gil Birmingham

Music by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis

Cinematography Giles Nuttgens

Edited by Jake Roberts

Running Time: 102 minutes

Rating: MA15+

Release Date: the 27th of October 2016

Images: Sourced from www.madman.com.au

Long before he was cast as “the Dude”, one of Jeff Bridges’ earliest roles was in Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show. This mini masterpiece of the 1970s depicted a town derived of any hope or future as stores and buildings closed down and people were faced with the depressing realisation that their ordinary lives were nothing but dead ends. Bridges, 66, now features as a racist Texas Ranger in Hell or High Water, which is both an exhilarating crime thriller and a black comedy that shares unexpected thematic parallels with Bogdanovich’s film and also No Country For Old Men (2007). Despite a lighter and more energetic tone, inevitable comparisons are being drawn between the film and the Coen brothers work because of the comparative use of the contemporary Western setting and the collective allegory about a decadent society. Set in Texas, the story’s focus is two brothers named Tanner and Toby, played by Ben Foster and Chris Pine, respectively. Tanner has spent time in prison for murder and Toby is looking to pay child support as he and his wife have separated.

To raise the money and to put a farming property into a trust fund for the children, the brothers opt to rob a number of local banks, ensuring that the corporations unknowingly spend their own money to secure the future of Toby’s family. There are men of poor moral judgement in this film, but they’re free of cheap movie labels such as “the bad guys”. Instead, the plot cuts between the brothers and Marcus Hamilton (Bridges), so that as the robberies are under investigation we become aware of Toby’s desire to raise enough money for his legacy and absorb the intentions behind his violent actions. Effectively, our sympathy for the characters is spread evenly as they engulf a colour spectrum more transcendent than the black and white labels of their archetypes. All the major characters are selfish, flawed and repugnant in their actions, but the gift here that modern cinema all too rarely offers us is that we come to understand the social and political forces that have shaped them into who they are.

Matching the strength of the film’s themes is the tragedy that British director David Mackenzie and screenwriter Taylor Sheridan (Sicario) have framed the characters within, dramatising how people of different values and cultures are blindly at war with each other, in spite of their common enemy. All of the film’s characters are disillusioned with the greed of the banks, having taken peoples’ houses and money in a depressed, post-GFC period, which illustrates similar economic bleakness to Bogdanovich’s world of the haves and have nots. But David Mackenzie also employs his own unique visual grammar to illustrate the economic theme. Set to the beats of a toe-tapping soundtrack by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis, beautiful wide shots with deep focused backgrounds show the sparse open countryside, implying the emptiness of the country’s future, while the motion of the camera crabbing sideways as it breezes past houses and financial billboards is an expression of the fleeting nature in which financial institutions enter and exit people’s lives and homes, thereby referencing the damage of foreclosures.

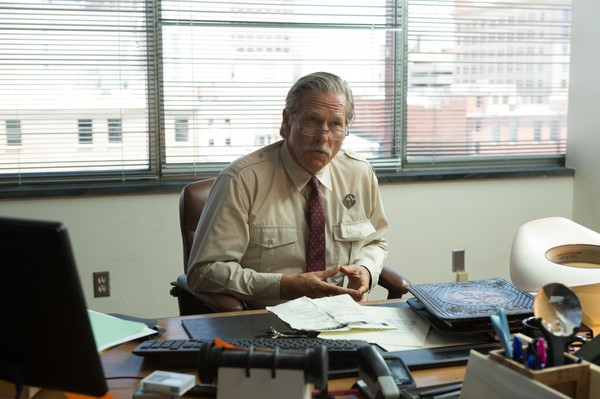

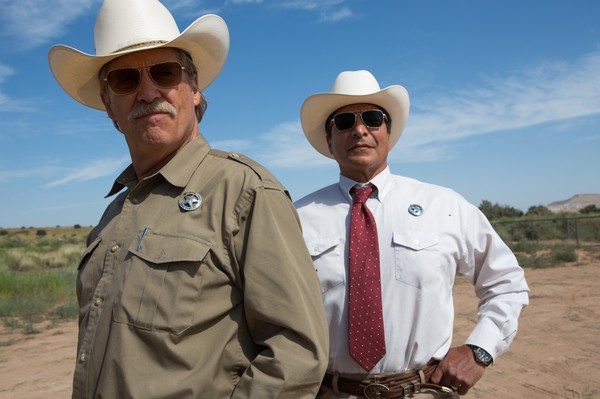

The expendability of human nature lives deep too in the characterisation. Bridges’ Marcus is not simply an ageing Ranger but a dinosaur with a badge and whiskers. He is a bored, out of touch racist who aims his darkly funny barbs at his partner Alberto (Gil Birmingham), an Indian cop, and feels that a blaze of glory would be his one salvation from the terror of retirement. One small touch is that one of the banks Marcus investigates does not have proper surveillance recording technology, which humorously sketches him as an anachronism in his surroundings. Alberto also becomes a surprise beacon of sympathy and hopelessness. He voices cultural theft, arguing his ancestors’ land was stolen by the banks, the very institutions he and Marcus must now protect. Lastly, the film’s depleting hourglass exposes gun violence—a comment on America’s anachronistic attitude towards firearms—where in electrifying bursts of action and verbal grandstanding ordinary people wield their own moral badges and try to stop crimes unfolding as though lynchings never died but are a single rope length away. The story is etched in as much irony as aggression: people are drawn to the defence of the banks, the very institutions that continue to repress the working class and blue collar people. If Hell or High Water was developed a year ago or more, this idea is precise and eerie in foreseeing the psychological contradictions and blindness unearthed in the current US election.

The complex thematic goals of time and economics are further enriched by strong visuals and impressionable performances. In an early action sequence, David Mackenzie’s camera is excitingly fluid, allowing us to speed behind and inside the brothers’ getaway car, exposing us to the rush and excitement drawn from a risky escape. Simultaneously, he draws explosive energy from Ben Foster, in his best role since The Messenger (2009), who is the deadlier and more unpredictable of the brothers, and whose only real love is the thrill of a crime spree and never a human heart; he comments that he was even too much for his own mother. While he helps his brother, this is also a death wish disguised as loyalty. His life is empty and aimless, which makes him a shallow creation and complex all at once. Meanwhile, Chris Pine as Toby displays a penchant for minimalist acting with an unexpectedly reserved performance as a man ashamed of his own violent actions but who is desperate to consolidate his family’s future. In a quiet, brilliantly observed scene shared between himself and his son over beers, he gives one instruction to his boy. “Don’t be like us”, he says, further illustrating his desire to tear his son away from the crime world.

Jeff Bridges does his best work since True Grit (2010), playing a character similar to Tommy Lee Jones’ role in No Country, but also darker and funnier. The fact that he draws big laughs as he hurls terrible insults at his partner highlights his excellent comic timing and the sharpness of the writing. Hell’s dialogue brims with Southern wit. The humour is an unexpected treat—a reprieve from the violence and machoism—and the dialogue is more colourful and funnier than many films I’ve seen this year. The comedy is matched by a tremendously tense crime thriller and a character study where admittedly, we work hard to see if these men are deep and complex in their terrible ways or just simply terrible. However, if one struggles to answer this question throughout the film, the closing of the final scene solidifies the story’s meaningfulness. It is a bullet-free showdown of words, a breathless, nerve-racking display of powerhouse acting, where two men have holstered their guns momentarily but their fingers continue to gravitate towards the trigger because it is the only means in which they can protect the purpose of their lives. As the film’s title suggests, one must either live in sin or be swept away. While the rest of the world fades, these two characters unearth such a deep stubbornness about who they are that not even death will deter them from their newfound goals. They are both the heroes and villains of a world that is seeing the last very breaths of the individual.

Summary: Hell or High Water is both an exhilarating crime thriller and a black comedy that shares unexpected thematic parallels with Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show and also No Country For Old Men.