GEORGE TAKEI INTERVIEW

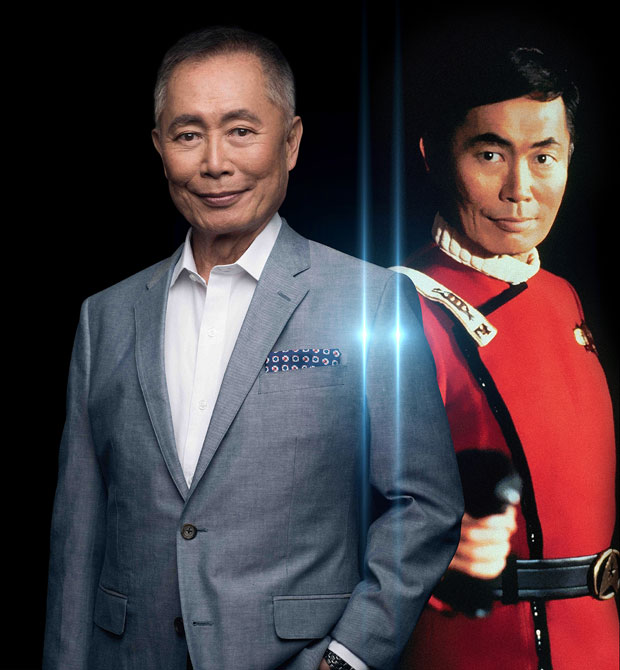

Social media sensation, human rights activist and singular pop culture legend, George Takei, was recently in Australia for “THE GEORGE TAKEI PHENOMENON” – a two-hour live show where he went into detail sharing stories about his personal life and tales from his entertainment career.

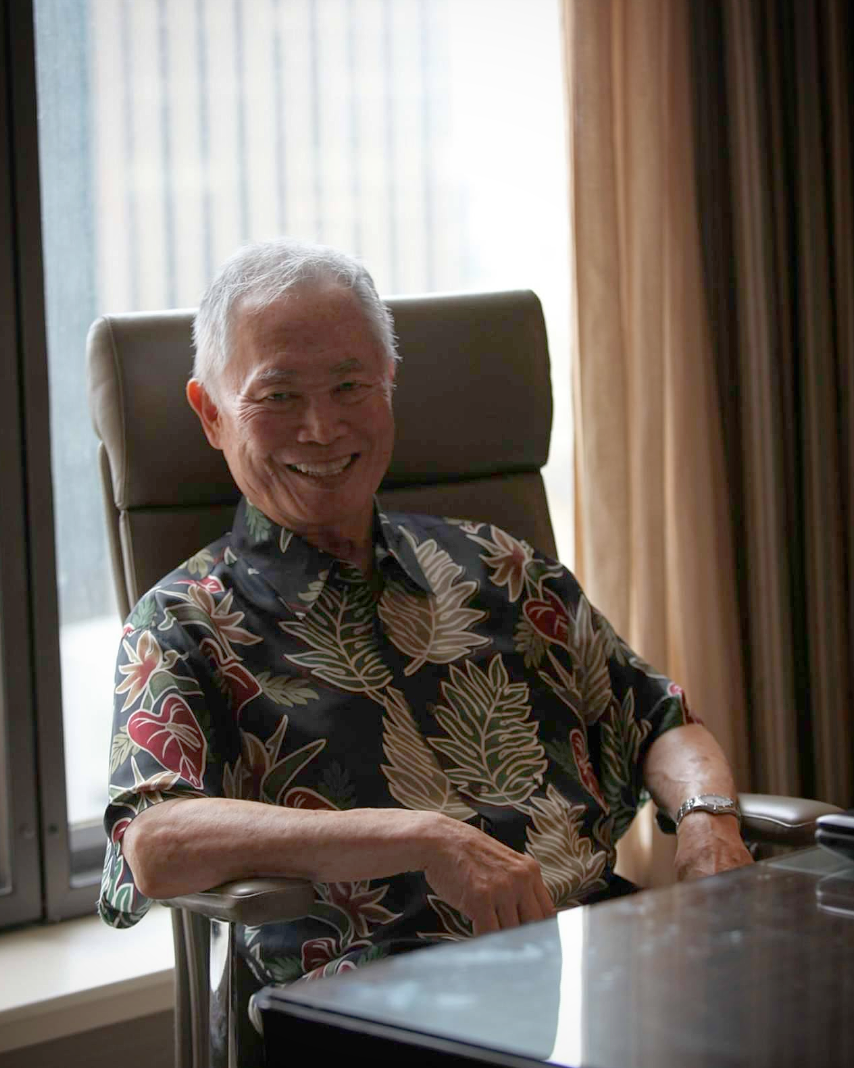

Impulse Gamer was lucky enough to have had the opportunity to sit down with George whilst he was in Sydney, where he shared compelling stories from his childhood, recounted the events that led him into acting, detailed his personal career highlight and talked about the marriage equality plebiscite.

I grew up on Star Trek. I have very early memories as a child sitting down with my father to watch the films, The Wrath of Khan and The Search for Spock. I can reflect on often hearing the music playing out from my parent’s room late at night, and often hearing that iconic music from the Original Series playing in the background of my mind. I fell deeply in love with the stories and the characters, and found it very easy to immerse myself in this world of high adventure and space exploration.

So, to say that I was a little nervous whilst I was walking up to meet George was a gross understatement. As I approached his door, I held my breath with nervous anticipation and excitement, as I couldn’t believe that I was about to be meet Mr. Sulu in person! My nerves, however, immediately disappeared, as I was greeted by the most lovely, kind-hearted and generous person I could imagine. George immediately made me feel welcomed, and at once I relaxed and felt at ease, as I sat down to enjoy a very engaging chat with him over a nice warm cuppa.

This is a bit cheeky of me but I had envisaged you wearing your iconic leather cape costume from The Search for Spock for this interview today. Did Sulu only take one change of clothes when hoping to steal the Enterprise?

George: Well, interesting that you mention that, as that costume is now in a museum. Gene Roddenberry actually gifted that costume to me. The museum asked me for a donation and I thought that imminently deserves a place in the museum, so I gave it to them. Before they started the reconstruction of the department store as a museum, they had a preview exhibit for members of the academy and a few invited guests, and there was my uniform in the section for heroes. Prior to that donation we founded a museum called the Japanese American National Museum, primarily because of the internment experience during the Second World War.

My mother was born in Sacramento, my father was a San Franciscan, my siblings and I were born in Los Angeles. We were Americans. Born, raised, educated in the United States, but we happened to look like the people that bombed Pearl Harbour. We were summarily rounded up, with no charges, in the most egregious violation of the United States Constitution and put into ten barbed wire prison camps. Our family was sent to the swamps of Southern Arkansas, and this story is still little known in the United States, and it’s been my mission in life to raise the awareness, as it happened to the Japanese Americans, but it also happened to the US Constitution which every American should be concerned about. So, from my late teens to today I’ve been going on tours lecturing on the imprisonment of innocent people. The reason why I do this, is that most people don’t know this story.

So, we founded this museum to institutionalise this as a story, so that it won’t die, and those of us who experienced that, when they pass on. We are an affiliate of the Smithsonian, which is our National Museum in Washington DC. So that’s been my mission in life. So, I’m now part of the museum world, the Chairman of the Board of the Japanese American National Museum, so when the academy decided to build a museum I became very interested in that and became a financial contributor and so I donated my Sulu costume.

The quietly iconic Sulu movie costume.

George: I also wanted that story and my Star Trek association to be kept alive. Our docents were puzzled because so many Star Trek fans were coming to the museum. Before it was scholars and people that are history oriented, but here are people who are Trekkies.

It is an important artefact. You’re one of these people who have become an iconic character and that costume itself is now iconic. I actually wanted to talk more about your experience as a child, and just how that was for you being so young. How did that whole experience shape you into the person you are today. How old were you when you first went there?

George: I was five years old. Very young. You know, I have vivid memories but they are the memories of a five-year old. I do have memories of my parents and their anxiety and so forth but they’re peripheral memories. The honest memories that I have, the ones that were most engaging are discoveries…of adventure. My father said we were going on a long vacation in a place called Arkansas, and that sounded exotic. You know, like going to Hawaii. That one terrifying day that I remember was when my parents got me up very early one morning, together with my brother, a year younger, and my baby sister who was an infant, and they addressed us hurriedly. My brother and I were told to wait in the living room, whilst our parents did some last-minute packing back at the bedroom, and so they two of us were just gazing out the front living room window, when we saw two soldiers marching up our driveway, carrying rifles with shiny bayonets. I remember the bayonets shining because it was morning. They stomped up the front porch and with their fists began pounding on the door, and at that time it seemed like the whole house was vibrating. My father came out and answered the door and literally at gun point we were ordered out of our home.

How awful for you. Being a child experiencing that at such a young age.

George: We were frozen. It was terrifying. My father gathered my brother and me and our little pieces of luggage, a carboard box tied with twine, to carry and he picked up two heavy suitcases and went out. We followed him out and stood out on the driveway waiting for mother to come out, and when she finally came out, she had the baby in one arm, a huge duffle bag in the other and tears were streaming down her cheeks. It was a memory that I can’t erase.

From there we were taken first to a race track, Santa Anita racetrack in Los Angeles, and we were herded over to the stable area. Every family was assigned one horse stall, which still stank of the smell of horse manure. So, for my parents going from a two-bedroom house on Garnet street, and taking their three young children to sleep in a horse stall, was degrading. But to me as a five-year old boy, I thought, ohh this is where the horseys sleep. I remember that, particularly looking back on it as a teenager and I wanted to find out more about the other truth; my parent’s truth of that incarceration experience. So, I had many after-dinner conversations with my father and he shared with me both the humiliation, the rage, the bitterness and the degradation that he felt.

I remember the barbed wire fence when they confined us in Arkansas. I remember the tall sentry tower with machine guns that pointed at us. I remember the search light that followed me at night when I made the night runs from the latrine from our barrack. To five-year old me, I thought that it was nice that they lit the way for me to pee, but for my parents it was invasive. Children are amazing, they adapt. Lining three times a day to eat lousy food in a noisy mess hall became routine. Along with my father and brother bathing in a men’s shower was normality. I went to school in a black tarp barrack, and beginning the school day every morning, pledging the allegiance to the flag. I could see the barbed wire fence and the sentry tower right outside my school house window, as I recited the words “with liberty and justice for all” – an innocent kid just reciting the words my teacher taught me. So that’s my childhood experience.

How long were you there for?

George: We were there for roughly a year in Arkansas, and then it was a series of outrages. The next outrage came. They came down with a loyalty questionnaire. Outrageous. Right after Pearl Harbour bomb, young Japanese Americans, despite the hate that was flung on us, rushed to recruitment centres to volunteer to serve in the US military. That was an act of patriotism that was answered with a slap in the face. We were denied military serve and categorised as enemy aliens. We were neither. It was totally irrational. We weren’t the enemy. They were volunteering to possibly die for their country. Do you call these people enemy? They were born, raised, educated and spiritually American. They wanted to volunteer to fight, and to call them aliens was crazy! And then they came down with a curfew, all Japanese Americans had to be back home by 8pm and stay at home until 6am. We were imprisoned in our homes at night. Then we discovered that our bank accounts were frozen, that our life-savings became inaccessible. We were financially straightjacketed and then the President signed the executive Order 1066. For us to be rounded up, 120,000 of us approximately, and imprisoned in ten barbed wire prison camps. Some of the most hellish places in the country. We were sent to the feted swamps of Arkansas. Others were sent to the High Plains of Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and two of the most desolate places in California. Then after they imprisoned us and kept us prisoners for a year, they came down with the next outrage: a loyalty questionnaire. They demanded loyalty after all that outrage. The most egregious offense of that questionnaire, was question 28, which was one sentence, with two conflicting ideals. It asked, “Will you swear your loyalty to the United States of America, and forswear your loyalty to the Emperor of Japan?” We’re Americans and they assumed that we had a racial loyalty to the Japanese. It was offensive. Don’t they know we’re Americans? We volunteered to fight for this country, and now they want to say we have to forswear our loyalty to the Emperor. It was really galling. So, if you answered no, I don’t have loyalty, that applied to the first part of the sentence. If you answered yes, meaning I do swear my loyalty to the United States, then that yes meant we had an existing loyalty.

Ahh, so it was like a trick question?

George: Yes, yes, it was. We’re confessing that we have been loyal to the Emperor and now we’re forswearing it, setting it aside and repledging our loyalty to the United States of America, and the amazing thing is that thousands of men and women swallowed the bitter taste and answered yes to that outrageous question, and they went to serve. They were put into a segregated, all Japanese American unit and they were sent to Europe. Used like cannon fodder, sent out on the most dangerous missions. Missions, where other attempts by the rest of the army had failed and we were supposed to be the final wave. They fought with amazing, unbelievable courage and determination, because they were fighting to get their families out of prison. They were out to prove that they were Americans. They sustained the highest combat casualties of any other combat unit of comparable size in the Second World War. Because of that kind of heroism, they came back as the single, most dedicated unit of the entire Second World War. They were greeted back on the White House lawn by US President, Harry Trueman, who said to them, “You fought not only the enemy, but prejudice, and you won.”. That was another group of Japanese Americans who went from barbed wire imprisonment. There was another group that had the view that, I’m an American and I will fight for my country, but I will fight as an American. If I can report to my hometown draft warrant, with my family back home, I will be like all Americans and have something to fight for, I will fight as an American, but I will not go as an internee, leaving my family in imprisonment to wear the same uniform as that of the sentries guarding over us. I will fight as an American. This was a gutsy position. To take on the full might of the United States Government, saying I’m an American and I will fight as an American. It was a very principled position and a courageously American position and they were tried for draft evasion and found guilty and transferred from an internment camp to the federal penitentiary. They were as courageous as and gutsy as those who fought on the battlefield. Their battlefield was behind the tall concrete walls of a federal penitentiary, but they stood strong in their faith in the fundamental basic ideals of American Democracy, and I honour them. I am proud of them. They are American Heroes equally. That loyalty questionnaire fractured the Japanese American community into groups like that. Each made that fierce commitment to their position, which meant that they started vilifying each other, and that division in the community still exists to this day.

We developed this musical, that we first performed in San Diego at a very distinguished regional theatre. We needed to find investors for this musical, Allegiance, and so we had readings of the play in various pockets of the west coast, where affluent Japanese Americans lived. Japanese Americans who’ve become affluent are not risk takers, and Broadway is a real gamblers arena, but we felt that because of the story we are telling that these people would be persuaded to invest in our production. In one community in San Jose, after the reading, I was stunned. There were groups of people who were saying things like, “Your uncle who fought in the war contributed to my father’s alcoholism”. There was this one woman, an elderly lady, the mother of one of the resistors who went to the federal penitentiary who was a member of a church group. This group was made up of those whose sons had mostly gone to Europe to fight, and when they discovered that her son was a resistor, they ostracised her. This ladies group was her whole world. She was isolated and she committed suicide. So, they feelings were very intense and I was stunned. That was in 2011/12 when we were seeking investors, and what’s when I realised how important our story is.

The other shocking thing that I learned was so many younger Japanese Americans, after seeing this this musical came up to me and said, “My grandparents were in camp too”, and I said, “Oh really? So, you connected with the story? Which camp were they in?”, and they gave me a blank face. They don’t know because with many families they didn’t talk about it with their children. Many of them, the younger generation know that their parents were in camp, or that their dad fought in Europe, but that’s all they know. They don’t know the details. So, this really made me feel that we have an awesome, weighty responsibility to tell this story. Not only to the larger American community, but to the children of those people who went through that horror.

See, I didn’t know about the Japanese American soldiers going to Europe.

George: Oh yes, they are amazing heroes, but the resistors stood on principle, American principle. I consider this heroic as well.

What about your father?

George: My parents answered no to the questionnaire. So, we were transferred to the Arkansas camp to a high security camp in Northern California, called Tule Lake. It was not just one barbed wire fence, but three layers of barbed wire fences, and they had a half dozen tanks patrolling the perimeter. I mean, that’s really overkill. Those tanks belonged on a battlefield, not patrolling a camp of people that were goaded to outrage. A series of outrages, and they were angry and embittered, and then to react to it with tanks in the perimeter. But, there was also another reaction from some of the younger people there. Their position was, alright you’re going to consider us enemies despite the fact we’re American’s, so we’re gonna show you what kind of an enemy you can face. I remember waking up in the morning to these radicalised young men who were jogging around the block to be physically fit to rise up when Japan lands. They had the headband with the Japanese military symbol, the rising sun painted on it, and they were going, “wa shoi, wa shoi, was shoi”, running around the block, and they would end their jogs with “Bansai! Bansai! Bansai!”. Of course, the military police would come rushing in and they would scatter and disappear. They wanted to get the ringleaders, and so they would stage midnight raids. I’ve seen young men dragged out of their unit in the barracks and taken to the stockade, which was a concrete jail built by the people themselves. So, we had at Tule Lake, a jail within a high security prison camp. They were imprisoned in that hut because they were really a threat and dangerous. So, that’s my childhood background.

So, you’ve been politically active from quite a young age. Would you say it was your experience as a child that lead you in that direction?

George: That experience was a life defining experience, yes. As a teenager I became very curious about the real story, rather than my real memory of catching dragonflies, and putting red ants in a glass jar and watching them make their nests amongst the dirt. Those were fun memories. I wanted to know my parents experience and so I had many discussions with them. My father was a man who bore the burden, the loss and anguish and the rage the most, and yet he was able to explain to me that our democracy is a people’s democracy. That it can be as great as the people can be, but it can also be as fallible as people are. He said that President Roosevelt in the thirties was a great President. We were in the depths of a harrowing depression, and because of his political savvy and creative instinct was able to create jobs. He pulled the country out of this horrific depression, but Roosevelt was also a fallible human being. There was hysteria in this country after Pearl Harbour was bombed, and combined with racism, we had an attorney general in California, the top attorney in the state, who made the statement, “We had no reports of spying, sabotage or problematic activities by Japanese Americans, and that is ominous because the Japanese are inscrutable. We don’t know what they’re thinking. So, we should lock them up before they do anything”. So, for this attorney, the absence of evidence was the evidence, so it was a “good idea” to lock us up before we did anything. There was only one elected official who stood up for us and said this is unconstitutional, that this must not be, and his political career got destroyed. Roosevelt got swept up in that hysteria and he signed that executive order. So, my father said that our democracy is existentially dependant on people who cherish the ideals and will struggle for it.

I had read civics books and I said, “Daddy was wrong. I would have gathered my friends from school and gone downtown to the federal building and protested”. My father said, “Yes, I believe you would do that, but what do you think would happen if I did that? They were pointing guns at me. I had to worry about you, your mother, your brother and sister. If something happened to me, what would you do?” He told me that he would show me how a people’s democracy has to work. He drove me downtown to the campaign headquarters of Adlai Stevenson, who was running for president in the fifties, and here I was with other people who were passionately dedicated to getting this great governor of Illinios elected, and what’s when I understood what my father meant. Our democracy is fragile and minimally a citizen’s responsibility is to cast and inform the vote, but beyond that if you really care about those ideals, you give up yourself and volunteer. You have to care enough to actively engage in the democratic process. I learned about our democracy through that experience, and an amazing father. I realise now that I was blessed, that I had this man as special as my father was. It’s hard to believe that someone who lost so much and suffered so much and was degraded so much was still able to explain that to his son. I gave him a hard time. You know, the most arrogant people are idealistic teenagers.

Oh yes, teenagers always give their parents a hard time.

George: Yes, but someone that’s idealistic is REALLY arrogant. A man who was anguished so much after the internment experience. I hurt him too because one discussion got really heated and I said, “Daddy, you lead us like sheep to slaughter to the internment camp”. There was silence and immediately I realised that I’d hurt him, and that silence seemed to go on forever. Then he got up and went to his bedroom and closed the door. I felt terrible. I felt like going to his bedroom door and knocking and apologising but it was too awkward at that point, so I thought that I’ll apologise tomorrow. Tomorrow morning came and it was even more awkward, and I never did apologise. That’s one of the great regrets that I have. He gave me so much. Both my parents struggled to get back on their feet after the imprisonment. In life, you’ve got to do it when you can. The more I think on my father, the more I appreciate him. I was closeted for most of my adult life, and I never came out to my father, but I’d like to think he would have understood.

So, I’m curious, with your childhood experience and political drive, how on Earth did showbiz and acting come into the picture?

George: You know, you’re born with it. That hunger, and you’ve got to be a little crazy. You know, my father had my businesses after the internment. My father was block manager in camp. The camp was divided into blocks and he was the liaison to the camp command but he also had to resolve problems because people were angry and bitter and he had to resolve that, so he became something of a leader, someone the people went to for advice and counsel. When we came back to Los Angeles, it was still a hostile place. Our first home was on Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles but the people still came to my father for help or assistance with finding a job or finding a place to live, and so he opened up an employment office in Little Tokyo, the former Japanese American ghetto, and he found jobs for them. Jobs that paid a pittance and his fee was a small fraction of the pittance. After about three months, my mother made him quit that. Then he bought a dry-cleaning business in the Mexican American neighbourhood in East LA, and he built up that business and he sold it. Then he bought a grocery store in the African American neighbourhood and built it up and sold it. Then he went into real estate, when other Japanese American families were getting back on their feet buying homes and businesses. On Sunday’s he would take me on drives to construction sites, and I remember two big excavations he took me to. One was in downtown Los Angeles, Bunker Hill, and he said, “This is where a great performing arts centre is going to be built. The opera house is going to be here and the theatres are going to be at the far end”, and sure enough that’s the music centre of Los Angeles today. Then one Sunday he took me to another excavation site, where he said, “On this site will be built a big luxury hotel”, and that’s where the Beverly Hilton is today. I knew that he had expectations of me to be an architect. He wanted me to put up a sign that said, “Takei and son real estate development”, and I would design the building and he would develop it.

So, I began my college career as an architecture student, at UC Berkeley. I liked architecture but even there I was volunteering in the theatre arts department to be one of the Scottish soldiers, with this face too! They had lots of hair to cover my Asian face. That was a lot of fun. From the time I was a child, even in camp, I had that burning desire. After two years as an architecture student, I just couldn’t see me as an architect. So, I came back to Los Angeles and I said, “Daddy, I’ve got to be true to myself. I want to try my way as an actor”. I told him that I wanted to go to New York and study at the actor’s studio and really learn how to be a good actor. That’s where all the great ones are coming from. James Dean, Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift. He said that he’d read enough to know that the actor’s studio won’t give you a diploma that says you’re a legitimately educated person. Your mother and I want you to have that. If you must study theatre and acting right here in town in Los Angeles we have UCLA that has a fine theatre and arts department, and when you finish there, they will give you a diploma that says you are legitimately educated. He knew that I was a bull-headed kid and would insist on going to New York. So, he told me that New York is a crowded place, that it’s a very competitive place and a very expensive place, and that I’ll have to be prepared to do it all on my own. But, he had a deal to make with me. He said, “If you go to UCLA, we’ll subsidise you. So, you choose. New York on your own, or UCLA with a subsidy?”. I made a self-discovery, that I’m a practical kid. So, I went with the subsidy and I did deliver that document and my father was pleased.

As it turned out daddy was right again, as I was seen in a production in UCLA by a casting director from Warner Bros studio, and from that I was plonked into my first feature film. A film based on a novel by Edna Ferber, a very popular novelist on Alaska and it starred Robert Ryan and Richard Burton. All my scenes were with Richard Burton. Even the two-week location we had in Alaska. I then became a major donor for this household, and I aged from like 17 to like 80, or something like that. I know where all the skeletons in this household are encased.

Wow. So, you’ve had an amazing career. I know it must be hard for you to pick one, but what has been a personal highlight for you?

George: I think Allegiance. The story about the Japanese American incarceration, and this one fictional family which is fractured, just like the community itself was. A brother and sister go the opposite way. The brother, who is really my character, I’m telling the story and I bookend the drama, is determined to serve and when he answers the loyalty questionnaire, he goes off to fight. The sister falls in love with a young law student, who is a resistor and so they become estranged. She marries him and has a child. When he comes back from war and sees that she’s married to the very type of people that he hates, he calls him a coward and a traitor. Those words are words that really were spoken. There was a Japanese American leader of a civil rights organisation, called the Japanese American Citizens League who was the executive secretary of that organisation and he was complicit with the government. He had good intentions, he wanted to lessen the horror but he was complicit and he saw those that resisted as cowards and traitors and he called them that. In fact, there was one person who I knew personally who was a young lawyer, just opening up his office in Portland, Oregon when Pearl Harbour happened, and when the curfew came down he knew that was unconstitutional. You can’t put on a curfew against a racial group just arbitrarily, and so he challenged the curfew and the internment all the way to Supreme Court, and he lost. He was in the Idaho camp, and the people in that camp tried to raise funds to support him. Mike Masaoka the leader of the JACL came in and broke up that support group. He became a very controversial figure. He was hated by one group and idolised by another. He’s the only actual historic figure that’s in the drama, but because of the fact that Mike Masaoka has descendants, we took those harsh words out of his mouth and put them in the fictional character of the younger me. And he calls his brother-in-law a coward and a traitor. It’s a very powerful and dramatic scene. So that project, I consider my legacy project.

We played on Broadway in 2015-16 and we reached that Broadway theatre crowd but this is a story we want to tell to all of America, so we filmed it using film techniques. We performed in an empty theatre, an empty house, with multiple cameras and a crane. So, we used film technique to dramatize this Broadway stage musical. We screened it last year, on December 7th, which was Pearl Harbour day, and we broke all records. We were in Japan before we came to Australia, for the Japan premiere for that film, the people of Japan don’t know what happened to Japanese Americans either, so we screened that film to great acclaim.

Finally, I have one last topic I’d like to talk to you about. So, you and Brad were in Australia when the results for the marriage equality plebiscite were revealed.

George: Oh yes, we were overjoyed that it happened here, only two years after we got nationwide marriage equality. We got marriage equality in patchwork fashion in the United States. Massachusetts got it first in 2003 and in 2008, five-years later, we got it in California. What makes Australia remarkable is that the people, in a landslide vote, supported it. Massachusetts got it from the state supreme court and we got it from the court as well, and nationwide it was from the court, so we got it from the judicial route. But you got it from the people themselves in a plebiscite, and it was a landslide. That is amazing.

Yes, the results speak for themselves. The plebiscite was actually quite controversial at the time. It was a risk.

George: Well that’s it. We’re gay and you guys are straight and we applaud and congratulate one another. What’s the difference? It’s the same thing. The other part of this is that it’s no bodies business, for people to say that you’re going to be illegal, you know it’s ridiculous. It’s your right to marry as you want and it’s out right. I love young straight couples because they are going to be producing the gay babies of tomorrow. People need to think of their children and be open-minded.