Exodus: Gods and Kings (3D) – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on December 6th, 2014

Fox presents a film by Ridley Scott

Produced by Peter Chernin, Ridley Scott, Jenno Topping, Michael Schaefer and Mark Huffam

Written by Adam Cooper, Bill Collage, Jeffrey Caine and Steven Zaillian

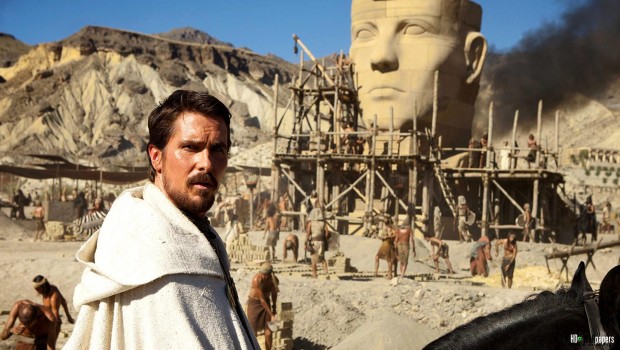

Starring: Christian Bale, Joel Edgerton, John Turturro, Aaron Paul, Ben Mendelsohn, Sigourney Weaver and Ben Kingsley

Music by Alberto Iglesias

Cinematography: Dariusz Wolski

Edited by Billy Rich

Running Time: 150 minutes

Rating: M

Release Date: December 4th, 2014

Ridley Scott’s Exodus: Gods and Kings is a grandly staged but soulless and mediocre retelling of Moses liberating the slaves of Egypt. It is one of two Bible films released in 2014, following Darren Aronofsky’s Noah, which envisioned a corrupt world cleansed of evil by a violent God and where a single man was enlisted to salvage a group of people. This description is applicable to Exodus given the over familiarity of its plotting and characters. The return of these Biblical epics is not only because Hollywood is heavily influenced by Christian values and religious groups in the industry. The popularisation of epics in the vein of Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments and William Wyler’s Ben Hur is also political. Currently, violence and extremism are perpetuated by radical fundamentalists misinterpreting religion. Bible stories are as current as they are ancient, relaying the Old Testament’s brutality and reflecting perpetually violent attitudes of modern extremists.

While Aronofsky’s film gambled on bleak, moody stylisation, Exodus’ treatment is safe and unsurprising, adhering to a fault to past filmmaking traditions. Prior to the film’s release, an online boycott was launched, attacking the decision to cast White actors in major roles of Middle Eastern characters. White imitation, where Anglo-Saxon actors impersonate ethnic roles, is an unproud, archaic Hollywood practice. Ridley Scott defended the casting in a Variety interview: “I can’t mount a film of this budget, where I have to rely on tax rebates in Spain, and say that my lead actor is Mohammad so-and-so from such-and-such.” His insensitivity doesn’t account for how White actors today would be forbidden from playing a Black character, particularly in America. Similarly, given Hollywood’s oversaturated marketing budgets, would it be too difficult to sell the film on Scott’s name alone or introduce new actors to the world?

Casting recognisable stars detracts sharply from the film’s period rendering. Featuring Englishmen Christian Bale and Ben Kingsley, Americans Sigourney Weaver, John Turturro and Aaron Paul and Australians Ben Mendelsohn and Joel Edgerton, there’s a wave of familiar faces and accents jarring with the setting and typifying the film’s homogenisation. Rarely does an image, a line of dialogue, or character feel unique to the film either. The opening quarter particularly mimics Scott’s Gladiator too closely. Moses (Bale) is a more skilful warrior and tactician than his half brother Ramses (Edgerton). He saves Ramses life in an early battle scene and Ramses’ father Seti (John Turturro) seems to favour him more even though he is adopted and unlikely to become the next Pharaoh. After investigating the thieving shonky practices of Hegep (Mendelsohn), Moses’s true Hebrew heritage is explained to him by Nun (Ben Kingsley). Hegep reveals this to Ramses, who forces Moses into exile. Moses starts a family of his own in a village, with a wife and son. After hitting his head he is plagued by visions of God inhabiting the body of a young boy (Isaac Andrews), who encourages him to free the Hebrews from enslavement. His fate of being exiled, his goal and motives are highly similar to Maximus.

Bale’s inclusion accentuates the derivativeness of the archetype. Instead of a cape and a mask, Moses wields a gold sword. But like Bruce Wayne, Moses’s arc is typical of Hollywood characters searching for individualism. He predictably transitions from denying his legacy to liberating his people and reuniting himself with his family. The script rewritten by Steve Zaillian from Bill Collage and Adam Cooper’s drafts takes Moses through unnecessary detours. Ramses only considers killing Moses long after he’s exiled and a training montage where Moses teaches soldiers to fight is wasted when God unleashes the plagues instead. Moses becomes displaced from the story, except for a tangent where he disapproves of God’s methods of justice. The plagues of Egypt are admittedly disturbing and visceral, but the literal interpretation diminishes possibilities of Moses imagining God. One unsettling dramatic touch is cutting to Ramses’ family life before the plagues, which builds tension knowing his son’s fate. But Ramses isn’t a juicy villain but a weak symbol of hubris. Joel Edgerton doesn’t have a firm grasp on what angle to take, meaning we don’t entirely feel the emotion of his blindness and rage.

Once Exodus escapes its stifled first half, the rest of narrative from the plagues onwards is overly familiar, bloody and brutal and supplies the actors with predictable, punchline dialogue spoken in plain English. There was a chance here to touch upon refugees escaping war and enslavement. These are issues dramatised only through the rhythms of action set pieces. While Scott’s Robin Hood cut a new origin story into an old tale and reinvented the characters, there are fewer surprises about how this film develops because of how risk-averse it is with the narrative and the casting. While the scale of the film is huge and cinematic, it’s the finer attention to detail in the screenplay and the period which feel lacking. Imagination and distinction are not qualities one would expect missing from the director who made Alien and Blade Runner. But in his twilight year Ridley Scott is determined largely to make epics of numbers rather than people.

Summary: A grandly staged but soulless and mediocre retelling of Moses liberating the slaves of Egypt.