James Marshís Project Nim (2011) is something of a fractured

biopic. It tells the story of Nim Chimpsky, a chimpanzee reared by

humans in order to investigate whether it could eventually communicate

by American Sign Language. The head of the project, Columbia Professor

Herbert S. Terrace, sought to refute Noam Chomskyís theory that language

is inherent only in humans.

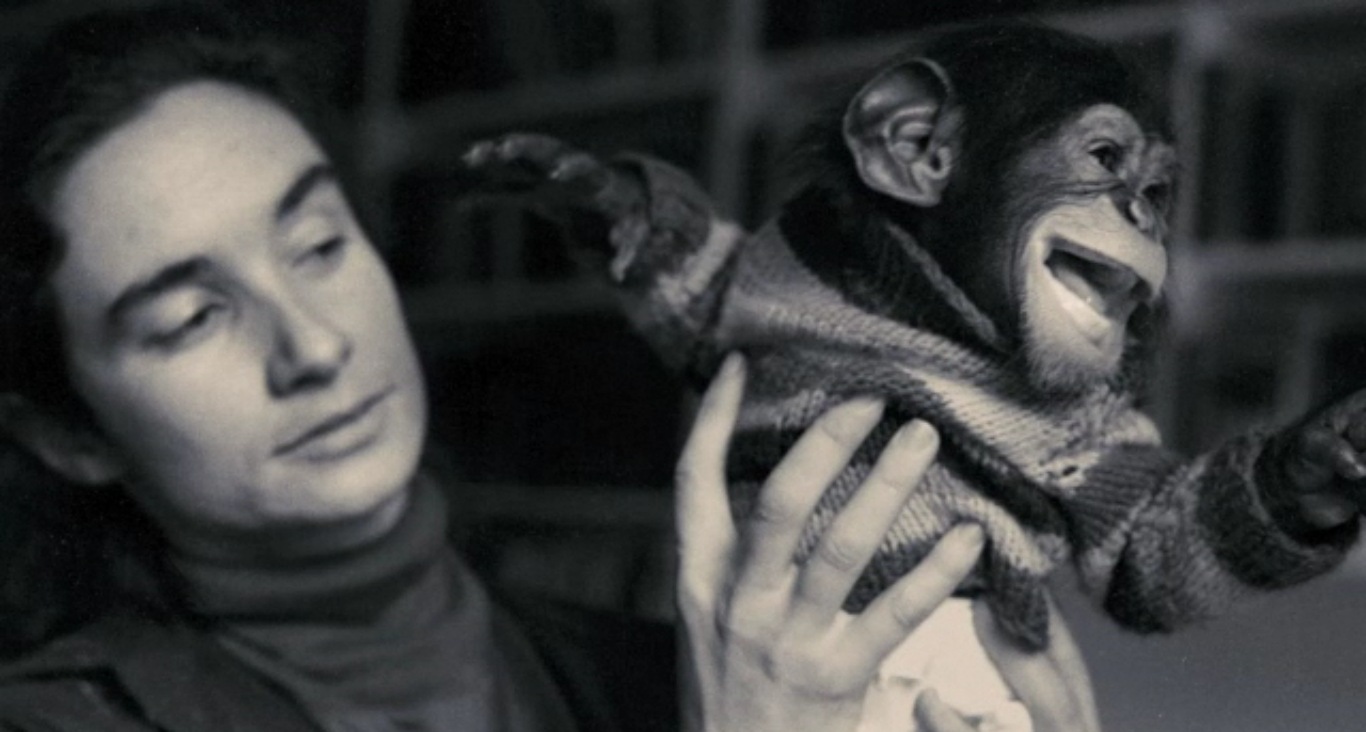

Accordingly, he obtained a two-week old chimpanzee and placed it in the

custody of a hippie Manhattan family, mandating that it be raised like

an ordinary human child. Marshís documentary draws inspiration from

Elizabeth Hessí book, Nim Chimpsky: The Chimp Who Would Be Human

(2008), which argues against Terraceís project. In Project Nim,

however, Marsh takes a backseat, allowing the individuals principally

involved in Nimís life to reconstruct the story.

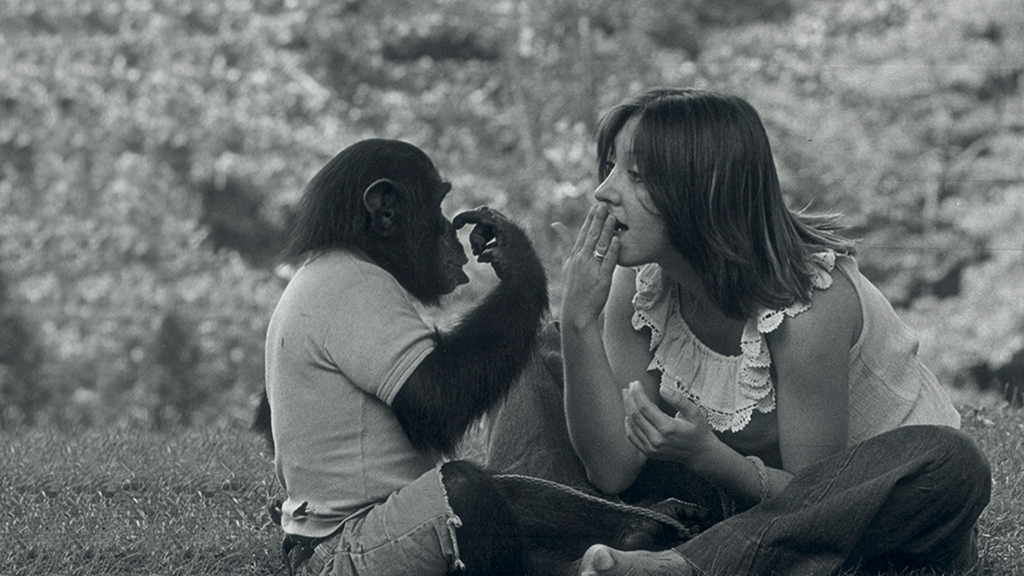

Nimís caretakers play a formative role in his education, however, what

is unexpected is Nimís role in shaping theirs. This powerful mutuality,

representing the central thrust of the documentary, is artfully captured

through a collage of home video

footage, candid interviews and dramatic reenactments.

Throughout the feature, Nimís

behaviour oscillates between an eerie human likeness and primal impulse,

thereby complicating his carersí feelings toward him. In one scene, for

example, he cradles a cat with utmost gentleness but in a later scene,

he is depicted dismantling the face of his language teacher.

However, Nimís worst crimes pale in comparison to the heartless manner

in which he is raised: as a mere experiment, to be discarded when no

longer required and abandoned to the whims of fate. With growing

uneasiness, the viewer observes Nimís tragic descent from celebrity

primate to LEMSIP test subject and finally, to an isolated misfit at

Black Beauty Ranch (a Texan ranch specialising in the care of formerly

abused equines). Ironically, by relating Nimís life as a failed test

subject, Marsh paints a dark and disturbing picture of human

limitations.

In the follow-up to his much-fancied Man on Wire (2008), Marsh

blends an intriguing ďnature versus nurtureĒ story with chic aesthetic

design, to a surprisingly woeful end-result. Decidedly, the filmís

downfall is its unforgivable lack of focus. Marsh manages to broach

several compelling issues but without examining any in sufficient

detail. As a result of this amorphousness, it is difficult for the

viewer to access the film on any meaningful level, whether intellectual

or emotional.

Illuminating this point are the filmís numerous interviews, which are

relied upon heavily to provide structure and emotional impact.

Chronologically sequenced to reflect the phases of Nimís life, they are

conducted with Dr. Terrace and his two research assistants (Stefanie

LaFarge and Laura-Ann Petitto), Nimís language teachers (Bill Tynan,

Carol Stewart, and Renee Falitz) and Bob Ingersoll, a deadhead

psychology graduate who befriends Nim, among others. As interviews go,

Project Nimís are passable. They are touching without waxing

maudlin and convey sincerity, without being soporific.

But in the end Marsh leaves behind too many loose threads. Trails of

beguiling stories are set down toyingly but are ultimately and

maddeningly, left untold. The dalliances between Dr. Terrace and his two

assistants, Nimís Oedipal Complex and the public apathy towards media

coverage of Nimís plight, for instance, are pushed to the periphery.

Marshís shelving of such potentially captivating topics seems careless.

The viewer is left frustrated and detached. It is this critical error,

as well as a panoramic scope, that renders any specific meaning, insight

or emotion hard to entertain, let alone engage with.