David Jeillings Interview

Hw did you become involved in the Museum of Australian Democracy (M.A.D.E.)?

We responded to a tender for multimedia design for the project, which is the way most museum projects get started. We joined an existing team including project manager Lateral Projects, exhibition designers Thylacine and Lucy Bannyan, curatorial team of Eithne Owens and Gabriel Maddock, and content experts to incorporate multimedia into the design of the exhibition.

Tell us a little about your background?

Many years ago I saw an ad pinned up on a notice board for a “slide mounter”. I was intrigued because I had some background in photography and was sure they had machines to mount slides. So I rang the number, and the lady who answered convinced me to come in for a four hour casual shift to see what it was all about. It turned out to be a company called Audience Motivation, who used to do huge multi-image projections for corporate events. That four hour shift turned into 17 years at the company. We did a lot of large corporate events and exhibitions, but the company occasionally used to produce multi-image experiences for World Expo pavilions and the occasional museum. Museums at the time were just beginning to get serious about the incorporation of media. Bruce Brown and I formed Mental Media in 2003, specifically to produce media for museums and exhibitions. Bruce had worked at Audience Motivation before I joined the company, and had gone to work in Europe before returning. We both really enjoyed the Expo and museum work and wanted to focus on it.

What can visitors expect to see and experience when they visit M.A.D.E.?

We hope that you’ll experience a desire to go out and get involved in the democratic process. The design team were concerned with the Lowy Institute poll that found only 39% of Australians in the 18-29 year old bracket thought “democracy was preferable to any other form of government”. We think that might be because a lot of people equate democracy to party politics, but really democracy is much broader than that. The curator wanted to encourage visitors to engage with the democratic process, become involved, start conversations and take action. M.A.D.E is not a traditional museum. Although it does contain the Eureka Flag and some objects, there is a lot of multimedia content and other types of interaction. Where objects are used, it’s often in a way that is designed to provoke debate rather than provide a definitive answer.

Tell us a little about the high-tech displays?

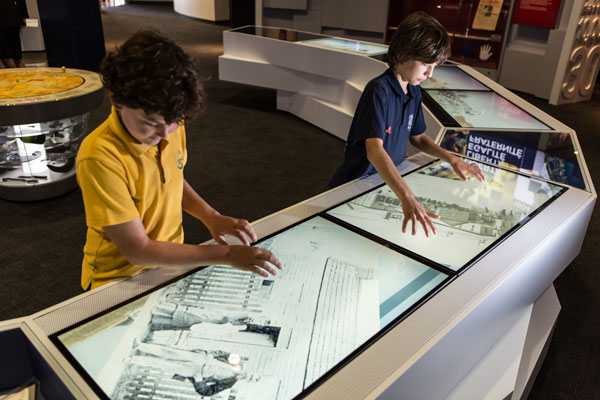

We used media and physical interactives in various ways to try to create “a-ha!” moments for the visitor – flashes of insight, not just intellectual engagement. Also, to create collaboration and interaction between visitors. There’s a large 10 screen multitouch table created by Lightwell that allows you to explore the entire Eureka story and add your thoughts.The “Power of Numbers” exhibit was inspired by the question “how many people does it take to start a revolution?”, but visitors can’t get the exhibit to work alone, they have to enlist their friends or strangers. You can literally immerse yourself in the “Power of Words” interactive room where famous speeches surround you in sound and image and the words will follow you around the room using motion sensing technology. You can then go and try making the same speech at a lectern in the theatre, complete with presidential teleprompters and instant video replay. Because people engage with exhibits in different ways, we were careful to ensure a variety of interfaces were used, from very high tech to quite basic.

What is your favourite display and why?

My personal favourite is the “Democracy Passport”, which uses face recognition technology to create an exhibit that actively discriminates against you on the basis of your physical characteristics. The facial recognition can tell your approximate age, gender, and facial expression and then use those characteristics against you. The design team wanted to give the visitor a very small taste of what it might be like to experience discrimination and powerlessness. Obviously we can’t even begin to simulate what real powerlessness or discrimination feels like, nor would we want to. What we did want was to trigger an emotional response in the visitor that would make them think about those who were experiencing real powerlessness. It’s an exhibit that’s designed to make you angry and frustrated.

What was the most challenging aspect about the technology behind it?

M.A.D.E has a lot of media content in a relatively small space, so one of the challenges is sound control. There are a variety of ways we use to control this, including focused sound speakers, automatic volume controls, and limiting the dynamic range of audio in production. Designing projection in some of the smaller spaces also required some thought. Durability and robustness is another challenge in any museum where you have lots of simultaneous users. There are several specialist or custom interfaces, including the face recognition and motion detection I mentioned earlier, which took some tweaking to get right.

Most rewarding?

Having the opportunity to interview a lot of extraordinary people for the productions, from senior politicians to political staffers, journalists, activists, psychologists, and pick their brains on how things work in a democracy on a practical level was a great experience for me. We wanted to give people a set of “tools” – inside information on the most effective ways you can participate, and just how easy it is.

Can you describe the Democracy = People + Power exhibit?

Democracy = People + Power is really the overall theme of M.A.D.E. The word “democracy” comes from the Greek words “demos” (people) and “kratos” (power). Eithne the curator wanted to get that broader definition across.

How many artefacts are contained at the Museum?

M.A.D.E has about 80 items on display in the exhibition space – these exhibitions are temporary and are changed regularly to enhance and compliment the permanent collection. The M.A.D.E collection is about 400 items, remembering that we are a largely digital museum.

What is your favourite artefact and why?

The Eureka Flag is an amazing object, very impressive, and the flag pieces on display have fascinating stories of their own. But I think my favourite object is a copy of the Coranderrk Petition, a petition from the people of Coranderrk Aboriginal Station to the Victorian Government in 1886, asking for some basic freedoms. It’s a very moving document.

Why do you think technology, especially interactive has been embraced by museums across the world?

Basically because museums know that done correctly, multimedia can really enrich the visitor experience. At the most basic level, it can provide multiple levels of information for the visitor to explore, more than would be possible using text or graphics. At the next level, visitors will learn more, and be more engaged, if they can take an active role. Good exhibitions do this naturally – they are stories and knowledge in 3D spaces that you can explore, and interactive multimedia extends this, engaging more of the visitor’s senses. I think it is particularly powerful in helping visitors connect with the subject matter on an emotional level and answer one of the key questions in any exhibition – “Why should I care?”.

Thanks for your time David!