Boyhood – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on September 4th, 2014

Universal Pictures presents a film by Richard Linklater

Written by Richard Linklater

Starring: Ellar Coltrane, Patricia Arquette, Lorelei Linklater and Ethan Hawke

Cinematography: Lee Daniel and Shane Kelly

Edited by Sandra Adair

Running Time: 165 minutes

Rating: M

Release Date: September 4th, 2014

Boyhood is an observant and sometimes profound marriage between fiction and reality. Individual growth is one of the most prominent and arguably over-used themes in Hollywood films because it is an expression of the freedom that people have living in a democratic society. Boyhood reinvigorates this thematic and ideological content by presenting it to us in a way we have never seen before. The director Richard Linklater filmed the same actors on screen for twelve years, tracing the life of a young boy from the age of six till he is eighteen along with his family including his parents and sister. We do not see a pre-planned character arc of development but real life and real physical development unfolding on the screen before our eyes. While adolescence and maturity have been thematic staples of many of Linklater’s films, navigating seamlessly between mainstream films (School of Rock) and independent features (the Before trilogy), Boyhood combines the director’s two film markets. The film is the relationship between a large, sweeping pastiche of nostalgia and cinematic memories for mainstream audiences, countered with an indie-like critique of the mental stasis faced by young adults and their parents as they grow older but fail to develop in their personal lives. It is not the director’s best or most even film, a degree of patchiness was inevitable in the way it was written and filmed, but the meaning Boyhood gathers ensures it outgrows any gimmicks to offer questions about whether life is progressive or merely circulatory as repeated situations and challenges test our character and maturity.

The only other film in recent memory that has a scope as large as Boyhood is Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life. Despite both films being preoccupied with the notion of evolution from childhood to an adult, these two films have differing stylistic aims. Malick’s film is highly formal with the camera planned to address predetermined themes. Boyhood was more spontaneously constructed to appear less like a film and more life-like. Linklater filmed the actors only a few days for each of the twelve years. He was granted only two-hundred thousand dollars per year for filming and writing the film took place sometimes the night before shooting. The way that the film is shot is also reserved, relying on natural lighting and minimal camera movements. Conversations, like a discussion between Mason and a girl walking down a laneway, are filmed in long single takes and tracking shots with minimal distractions, placing the emphasis on the actors and making the film appear like a home video construction. To demonstrate the flow of time, pop culture references are gently inserted into the film, with particular attention given towards transitions in technology like the shift from Game Boys to Xbox games like Halo and then Facebook or the way the film opens with Coldplay’s song “Yellow” before a later scene plays Gotye’s song “Somebody that I used to know”. The high range of pop culture references and shifts in technology lays waste to the notion that films are limited in their scope compared to the duration of long running television shows.

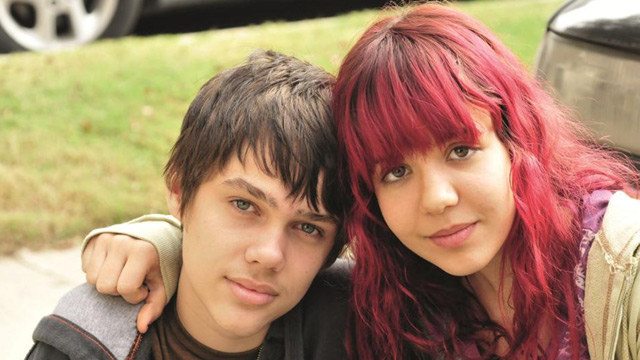

Encompassed in these long passages of time is the intimate story of a young boy named Mason Evans, Jr. (Ellar Coltrane) who from 2002 to 2013 develops into a young man despite the divisions in his Texas-based family. He does not get along with his sister Samantha (Lorelei Linklater, the director’s daughter) and his parents Olivia and Mason Snr. (Patricia Arquette and Ethan Hawke, both in top form) are divorced. Over the course of the film there are two major developments. Mason grows physically as a child but is uncertain of how to relate to people, particularly girls and his ghastly step fathers. For many years he is more interested in playing games than finishing his school work before becoming successful with art and leaving the electronics behind. He also shares a rivalry with his sister as they compete for the attention of their father when he visits. The film would have been solid but limited in its aims if it rested solely on Mason’s story. Instead, the thematic depth is expanded by the stories of the parents. Having starred in the Before trilogy, Ethan Hawke is a favourite actor of Linklater and each of his scenes ignites the film with infectious comic energy and humour. Critically, his performance holds our attention when Mason Jr. doesn’t have a lot of personality in his early life. When he arrives in a dodge muscle car to pick up his children we do not have faith in him but it becomes apparent that unlike Samantha’s other husbands his enthusiasm and guidance towards his children never falters. There is a hysterically funny scene when he encourages the kids to campaign with him for Barrack Obama and encourages them to steal John McCain signs from people’s lawns. It is fascinating how he never escapes childhood himself because even though he matures he returns to the phase by parenting a second family.

Mirroring Mason Snr.’s story is Olivia, whose judgment is regularly tested by the awful men she decides to marry. She tries relentlessly to provide for her children by developing an education of her own, studying psychology as an adult, but this only leads her into poor relationship choices. All her future husbands are surrounded by alcohol, a reoccurring motif throughout the film. One flaw is how broadly these husbands are painted like Professor Bill Welbrock (Marco Perella) who not only yells at her kids and his own but searches their phones and smashes things, which is portrayed through a melodramatic style of performance rather than a naturalistic register like the other actors. There is also a prison guard who is equally as heavy-handed towards the children. Although these two characters seem one-dimensional they are imperative to the film’s ideological aims: where these men are strict and dogmatic the film shares a highly liberal, democratic overview that stress our choices, both good and bad, determine our life experiences.

On these grounds Boyhood might not appear that different from many other American films that present the power of individuals to express themselves and their willpower to grow. I believe Before Midnight is a better film because its ideological discourse is much wider and more consistently filtered throughout the entire film, which runs less than two hours long compared to 165 minutes here. The very nature of Boyhood’s structure, Mason Jr.’s maturity from a shy, introverted kid and into an articulate and thoughtful young man, means it takes longer for the film to reach its life questions. It still gives us plenty to mull over, particularly a pivotal question Mason asks about whether it is possible to have an experience in life that is unique to ourselves. I think if people fall into cycles and habits, like bad relationships, what makes these moments unique to a person is what they learn from them. Mason might say the most awkward thing to a girl at the end of the film, a situation familiar to many people, but he will remember it and learn from it which makes it a personal experience. This is the film celebrating its democratic facet: our experiences of familiar situations are personal to us because we live in Western countries where as individuals we can make mistakes in our lives but also have the free-will to learn from their cyclical nature and eventually make the right choices, which is how we grow from children and await its sequel: adulthood.

Summary: Boyhood is an observant and sometimes profound marriage between fiction and reality.