Though both sides had extensively

utilised propaganda during World War I and the technique was

likewise to flourish throughout the Soviet system, no one group made

more protracted or effective use of propaganda than the Nazis.

In the two decades preceding their

demise in 1945, Hitler’s National Socialists produced many thousands

of posters, pamphlets, films and books designed to extol the virtues

of the party’s infallible leader or its many constituent factions,

though after Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933 the emphasis

largely shifted to railing against enemies both internal and

external. The two most prominent of these were, of course, Jews and

Bolsheviks, forces seen as essentially one and the same in the dark

recesses of Hitler’s fevered mind; to his final days he would rant

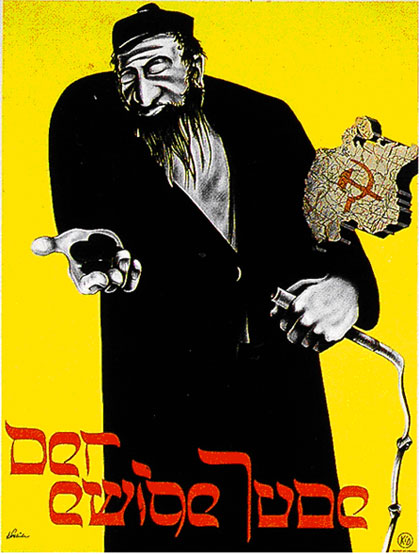

about the alleged crimes perpetrated by ‘international Jewry.’ This

obsession is evident in much surviving Nazi propaganda and spans a

variety of media, from the infamous 1940 film The Eternal Jew,

with its sequences superimposing images of ghetto-dwelling Jews over

those of rats escaping a sewer, to the children’s book The Poison

Mushroom, published by the infamous anti-Semite Julius Streicher

- one of the most chilling photographs in the present book shows a

handful of blond-haired schoolchildren innocently flicking through

this brightly-coloured, picture-filled grotesquery, which equated

Jews to toadstools and warned children how to spot these ‘criminals

and swindlers.’

But it was in the propaganda poster

that the Nazi penchant for artful vitriol found its fullest

expression. Masterpieces of the perverse that were frequently

produced by the leading artists of the period, such posters raged

against the Western Powers, the treaty of Versailles, Jews,

work-shirkers, Socialists, Communists and others, and comprise some

of the most striking, memorable and vitriolic examples of their

kind. Posters also praised the merits of Aryan blood, of youth,

family, land and liberty, in a powerful neo-Pagan style that is at

once potent and cloying.

State of Deception provides an

expert analysis of this shifting Nazi use of propaganda as well as

its role in promoting both community and conformity, and its 196

pages are littered with many hundreds of noteworthy examples, the

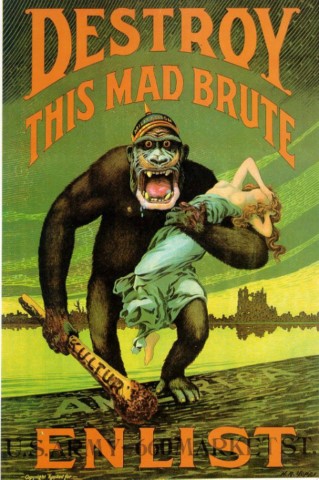

majority reproduced in full colour. Of particular interest are the

early chapters detailing British and American propaganda throughout

World War I. Whereas German propaganda had been content to portray

the enemy as ridiculous, its markedly more effective Allied

counterpart painted the Germans as a bloodthirsty horde to be

vanquished at all costs. Stories of bestial German atrocities

abounded, such as a supposed predilection for cutting off the hands

of young Belgian girls – that such stories were entirely untrue was

not important, for they combined effortlessly with posters depicting

the ‘Hun’ as a marauding ape sporting a spiked helmet and club.

Such a mentality pervaded much of the Nazi propaganda effort

directed against Jews and Russians: one of the most ardent admirers

of World War I Allied propaganda was, in fact, Adolf Hitler, then a

frontline soldier, and he evidently learnt his lessons well.

State of Deception is a

monumental work which expertly combines a fascinating historical

narrative with numerous well-chosen photographs, posters, leaflets

and other ephemera of this uniquely tempestuous epoch. It is a

thought-provoking and impeccably presented testament to mankind’s

aptitude for wilful self-deception, not to say debasement, and as

enlightening an encapsulation of the ‘age of propaganda’ as has ever

been attempted.