Faber imprint Faber Finds is the

self-styled ‘place for lost books,’ rescuing long out of print

worthies from the trash heap of obscurity, and in the case of

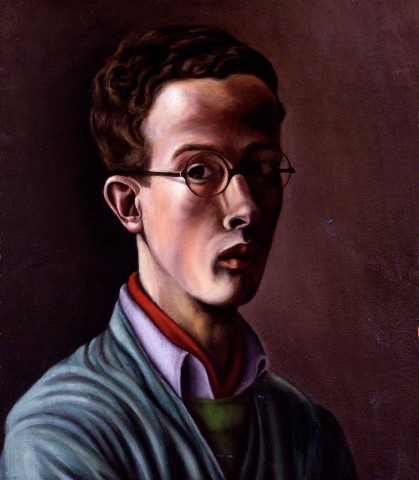

British author Denton Welch (1915 - 1948) their attentions could not

be better directed.

The son of a wealthy businessman, Welch

split his childhood between England and his adoptive hometown of

Shanghai. He was aware at an early age of his homosexuality, and in

his later life as an author took advantage of his ‘outsider’ status

to pen some of the most original and startlingly evocative prose of

the mid-20th century.

Having dismissed the Second World War

as ‘another example of the horrible devil-worship of grownups,’ he

turned his literary attentions to the more worthy topics of

eccentric acquaintances (‘his face looked like a very large,

scrubbed, kind potato’), a lifelong obsession with the minutiae of

daily existence (‘I felt the soft, silky dust grating between the

soles of my feet and the polished boards’) and the endless

frustrations of unrequited love (‘when you long with all your heart

for someone to love you, a madness grows there that shakes all sense

from the trees and the water and the earth’).

Welch spent most of his adult life as a

semi-invalid, having been struck by a car whilst bicycling at the

age of 20 - among the injuries which would eventually lead to his

death thirteen years later were a fractured spine and several

irreparably damaged internal organs. Though in his later years he

was bedridden for days or even weeks at a time (‘all life seems an

agony of sickness’) so skilled was he in the art of subterfuge that

many amongst his acquaintances and admirers were unaware he was even

ill. And although the wretchedness of his physical state

occasionally left him peevish and despondent, more often than not

his largely autobiographical writings are alive with the poetry of

one who sees (and feels) the world more keenly than most.

Describing a woman he had seen eyeing

him askance at a public bath, for instance, he writes ‘I wondered

why she disliked me so much. Perhaps she realised that I thought

her buttocks looked like full wine-skins.’ Of the eyeglass

innocently dangling at the waistcoat of an elderly associate: ‘It

reminded me of one of those little windows that vivisectionists let

into the stomachs of animals.’ And on his impressions as a boarding

school student after having received a caning from the headmaster:

‘The room was quite different when I opened my eyes. The light was

thick like milk and it seemed to float cloudily about the room.’

Whereas the characters of lesser novelists might merely grin, those

of Welch’s periphery are inclined to give a ‘wide, mechanical,

ballerina’s smile’ as they go about the ‘settled reverie’ of their

lives. Quite simply, there has never been a writer quite like him,

before or since. As one biographer aptly opined:, ‘I can think of

no writer who has described the extremes of physical and mental

agony with more appalling vividness than Denton Welch.’

Though this trend is somewhat

understated in Maiden Voyage, his first published work, all

the stylistic and thematic hallmarks that would later come to be

associated with his writing are nonetheless evident in spades;

Denton did not live long enough to suffer through any artistic

troughs, and the overwhelming bulk of his output is of the same

sublime standard.

The book is an account of his sixteenth

year, when he briefly ran away from his English public school and

later spent a year living with his father in Shanghai. The scenes

themselves are largely unremarkable - he hides out in hotels for a

few days, describes moments of timid, thwarted sexuality, and later

on travels to Nanking with a business associate of his father. Yet

the manner in which he paints these otherwise trivial vignettes, as

well as the people and objects which populate them, is a thing of

rare, resplendent beauty. Scenes come entirely alive, characters of

the most fleeting significance are evoked with startling clarity,

and his precise, analytical and unsparing eye recreates the foibles

of his fellow travellers in a way that is a marvel of contrasts,

somehow managing to be simultaneously charming and precious, funny

and sad, ethereal and yet wholly lucid.

Later, owing largely to the extent of

his injuries and his own impending sense of mortality, a gentle

undercurrent of sorrow ran through much of his work, imbuing even

the simplest of scenes with tenderness and urgency. He writes of an

outwardly serene 1947 picnic with Eric, for instance, that it ‘was

too sad to forget,’ and elsewhere attempts to reconcile his

considerable ambitions with his piteous health: ‘I want to get

something done, and shall do, I hope, if I don’t die.’ In Maiden

Voyage the emphasis was on hope; hope, as it turned out, for a

future that never came. It’s a brilliant and unforgettable book,

and one that deserves to be rediscovered by a new generation of

readers.