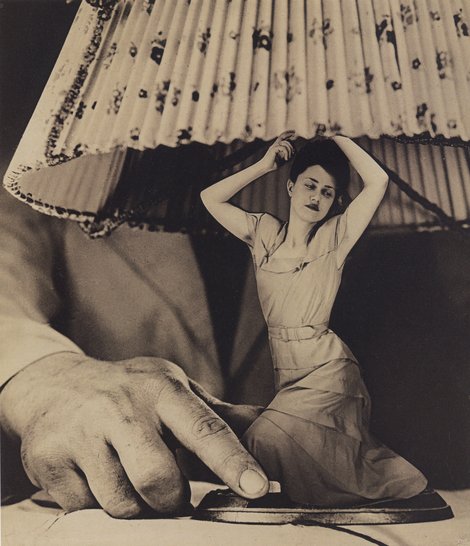

‘I would photograph an idea rather

than an object, and a dream rather than an idea.’ - Man Ray

It is tempting, living as we do in an

age of blatant photographic falsehood, to consider the art of

photographic manipulation a relatively recent phenomenon.

Celebrities are airbrushed to the point of absurdity, thighs and

waistlines are routinely trimmed to impossible dimensions and

blemish-free, preternaturally youthful faces stare from magazine

covers - oh, for the days when a photograph could be trusted to

provide nothing more than a direct, unadulterated representation of

the real.

As Mia Fineman points out in this

superlative new work, however, the art of photographic trickery is

actually every bit as old as the medium itself. Since the 1840s

amateur and professional photographers alike have been fastidiously

cropping and retouching their images, producing elaborate composites

artfully designed to fool the eye, adding and excising characters

from shots, utilising multiple exposure and other means to capture

scenes that would otherwise be technically and logistically

impossible, making wrinkles and imperfections disappear - in short,

for a century and a half photographers the world over have been

routinely and expertly employing the sort of visual sleight of hand

that has come to be associated almost exclusively with the digital

age.

The question of motivation - political,

aesthetic, financial or otherwise - comprises much of Fineman’s

brilliant 250-page narrative, which is adorned with hundreds of

colour and black and white images. Almost every photograph

referenced in the text is reproduced, in fact, with many of them

amongst the most important works from masters such as Paul Strand,

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Yves Klein, Grete Stern and Edward Steichen.

Fineman’s history of manipulated photography is breathtaking in its

expansive scope. Her wide-ranging arguments incorporate discussion

of technique, the various photographic schools, censorship, duelling

philosophies on the nature of photographic ‘purity,’ the use of

manipulated photography in wartime propaganda and the falsification

of images in regimes such as that of Stalinist Russia, where

murdered ‘enemies of the people’ were expunged from the photographic

record in an effort to remove any physical trace of their

existence.

In addition to seven sizable and

immersive chapters the book also contains a couple of hugely

worthwhile addendums, principal among which is a 50-page section

entitled ‘Discussions of Individual Works’ which incorporates

analysis of every major work represented in the text. A helpful

Glossary of Technical Terms is also included (anyone else inclined

to forget the difference between an ambrotype and a daguerreotype?)

as well as a fabulous Introduction which sums up in a mere 40 pages

all that is great and lasting about the art of photography.

As this impeccable work emphatically

proves, the camera can and frequently does lie. The story of how

and why it does so comprises one of the most fascinating titles to

ever be produced on the subject of photography, and another

virtuosic entry into the ever-burgeoning InBooks canon.