All the Money in the World – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on the 8th of January 2018

Roadshow presents a film by Ridley Scott

Produced by Chris Clark, Quentin Curtis, Dan Friedkin, Mark Huffam, Ridley Scott, Bradley Thomas and Kevin J. Walsh

Written by David Scarpa, based on ‘Painfully Rich: The Outrageous Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Heirs of J. Paul Getty’ by John Pearson

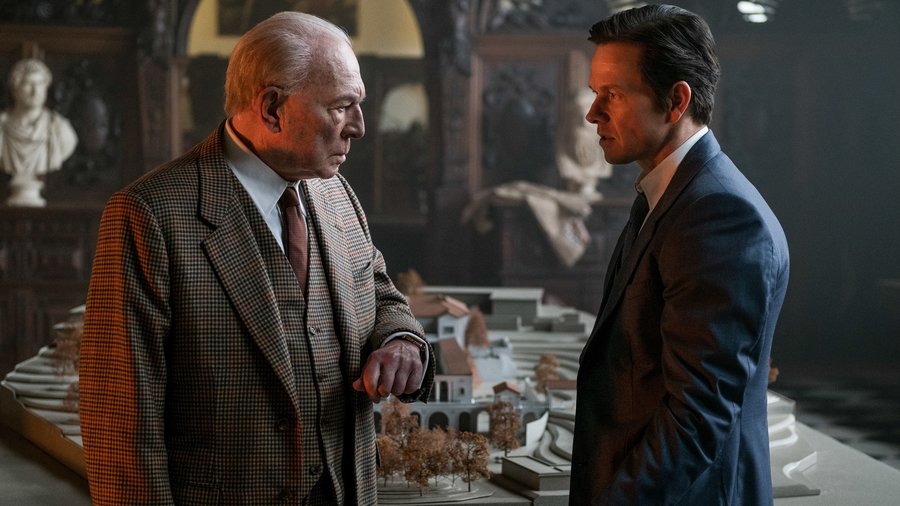

Starring Michelle Williams, Christopher Plummer, Mark Wahlberg, Romain Duris, Andrew Buchan and Charlie Plummer

Music by Daniel Pemberton

Cinematography Dariusz Wolski

Edited by Claire Simpson

Running Time: 130 minutes

Rating: MA15+

Release Date: the 4th of January 2018

It’s been said that if films became real life they would cease being films. It’s difficult wedging a real-life story into the parameters of a screenplay because events must be compressed to fit the requirements of the narrative structure. Ultimately, some great stories make bad films. Even with Ridley Scott’s experience, directing his 25th feature, All The Money in the World is one such example. The fascinating story of John Paul Getty and his resistance to pay his grandson’s ransom isn’t a layered piece of cinema. Despite a powerful cast, featuring Michelle Williams, Mark Wahlberg and Christopher Plummer, and a close eye to historical details, Money perpetuates Scott’s recently tepid form and failure to capitalise on the luxuries at his disposal. The title of this lukewarm thriller is befitting of its meagre quality.

The film opens in Italy in the 1970s where John Paul Getty III (Charlie Plummer) is kidnapped. In flashbacks, we see Getty III being raised by his struggling parents. His mother Gail (Williams) and Getty II (Andrew Buchan) describe themselves as “broke not poor”. They’re isolated from Getty II’s father, J. Paul Getty (Christopher Plummer), because he neglected the family to continue to make his fortune. Nonetheless, the old man sinks his claws back into them by offering Getty II a job in his oil tycoon business for which he is unqualified to perform. When the old man meets the family, he instructs his grandson to reply to his letters for him, suggesting his intent to draw him into his empire. He also tells his daughter in-law “you’re one of us now”, sending a visible chill down her back. These early scenes are promising because of these conflicts and some remarkably vivid images. A wide-angle lens of a massive oil tanker characterises the overwhelming might of Getty’s empire. Similarly, a low-angle shot of a department store building, owned by Getty, further visualises the volume of his wealth.

Nine years later, the old man’s posturing is apparent once Getty III is kidnapped. Getty II and Gail are now divorced, leaving her unable to raise money for the kidnappers, who want $17 million dollars. Worse, the old man refuses to pay the ransom because he argues it would only invite further violence against his family. He’s incredibly frugal, opting to do his own laundry to save money. His one positive choice is to organise for his main security leader, CIA agent Fletcher Chase (Wahlberg), to help Gail negotiate with the kidnappers. Meanwhile, Getty III is held in a dank cell in the impoverished Italian countryside. His only ally within the kidnappers is Cinquanta (Romain Duris), but he fails to shield the young man from being tortured.

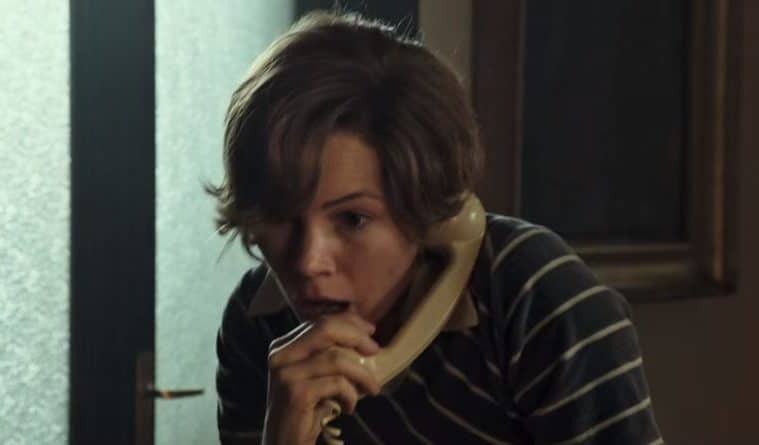

The major dispute between Money and the real story is perspective. Screenwriter David Scarpa has adapted John Pearson’s 1995 book on the subject, but his script is unclear about whose story he’s telling. It is overly fragmented in perspective, opting to be too generous to all the players at once. This dilutes who the central protagonist of the film is. The narrative structure would be better suited to a TV mini-series where different episodes could unravel each character. The film offers few thrills because there’s little momentum in the main plotline. The tension of Gail trying to escape this awful family but gravitating towards a capitalist nightmare is lost. There’s not enough for her to do besides talking to Fletcher and Getty and taking calls from the kidnappers. The film tries amending this in silly way, such as including Gail and Fletcher in a dangerous outdoor raid with the Italian police or featuring them in a contrived rescue sequence in the darkened alleyways.

The fragmented narrative structure takes its toll on the performances. Michelle Williams is one of the world’s best actresses. She embodies Gail with a breathless frailty that dutifully characterises the anxiety of losing her son, one of the only meaningful men in her life. However, constantly cutting away from her, rather than following Gail’s story, means we don’t feel the emotional strain this actress can capably display. Mark Wahlberg’s Fletcher was a real person, but the film is clueless about using him in the story. One cringing moment sees him spell out the film’s title as he blasts Getty. The film falsely attributes this as a major transition for Getty. Apparently, Gail’s father in real life talked sense into Getty.

Plummer, who reshot 22 scenes in nine days, effortless matches his own seasoned physicality to Getty. He exudes a ruthless oiliness that only a man who has consistently put his fortune ahead of his relationships could permeate. The real Getty was notably frugal and really did include a telephone booth in his house for long distance calls. Scarpa has mentioned his desire to transcend Getty’s similarities to pop culture figures, including The Simpsons’ Mr. Burns. However, due to some visual clichés Getty still registers as a silly caricature. The vision of a twisted old billionaire sitting in his shadowy mansion by the fire, while a booming opera soundtrack plays, invites unintentional laughs. It’s an image thoroughly parodied by shows such as The Simpsons.

Ariadne Getty, the sister of the real John Paul Getty III, argues the family wasn’t accurately portrayed. In an interview with the website Town and Country, she stated: “I think it’s a film that painted our family as only obsessed with wealth. That’s not the way that I raised my children. We weren’t raised that way.” Perhaps if Getty developed throughout the film, instead of when the plot required him to change, it would have been a balanced representation.

Charlie Plummer quietly express the anguish and physical pain of the young Getty, and often without dialogue. His scenes are suitably gritty, filmed in brown, moody tones. The ear splicing scene left the cinema audibly squeamish but showing this also seems a desperate ploy to find some much-needed tension. Money isn’t a strong examination of economics either. The Italian scenes fail to enhance the simplistic binaries between the wealthy Getty family and the impoverished kidnappers. Instead, the film regurgitates the same thematic point that Getty loved money more than his family.

Money is far less interesting than the scandals surrounding its development. Despite a handful of memorable visual flourishes and some decent performances, it fails to determine whose story it’s interested in unfolding. If it centred mostly on Gail and her emotions then the film would have fully utilised its best asset, Williams, and offered a tighter line of action. Instead, we see too much of some characters and not enough of others. The structure is overly fragmented and any significant thematic meaning about the differences between the rich and the poor is diluted. Director Danny Boyle is now planning a television series of the Getty story. Hopefully this will transcend the simplicity of this version of the story. It’s not all about the money.

Summary: The film is far less interesting than the scandals surrounding its development. Despite a handful of memorable visual flourishes and some decent performances, it fails to determine whose story it’s interested in unfolding.