Unbroken – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on January 12th, 2015

Universal Pictures presents a film by Angelina Jolie

Produced by Angelina Jolie, Matthew Baer, Erwin Stoff and Clayton Townsend

Screenplay by Joel and Ethan Coen (rewrites), Richard LaGravenese and William Nicholson, based on the book ‘Unbroken’ by Laura Hillenbrand

Starring: Jack O’Connell, Domhnall Gleeson, Takamasa Ishihara and Garrett Hedlund

Music by Alexandre Desplat

Cinematography Roger Deakins

Editing: Tim Squyres

Running Time: 137 minutes

Rating: M

Release Date: January 15th, 2015

Unbroken is so tightly screwed together by a conga line of big names and reputations we wonder how it could fail. It is a World War II biopic about Olympian runner turned fighter pilot Louis Zamperini. It’s Angelina Jolie’s second directorial effort, with a screenplay by Joel and Ethan Coen and photographed by multiple Oscar nominee Roger Deakins. For all its talent, Unbroken is a failure of overconfidence. It’s so sincere about honouring Zamperini’s tenacity and trusting in its ability to move us it never digs into moments between the violence but skims complacently along the brutal edges of its hero. Learning the most definitive moments of Zamperini’s later life haven’t made the cut also makes this survival story less distinguishable. The thematic and political goals it explores aren’t insightful or unexpected either but typical of films manufactured to inspire rather than allowing us to discover these emotions ourselves.

Opening the film is a well-constructed action sequence onboard a fighter craft. Zamperini (Englishman Jack O’Connell) is one of the fighter pilots. He and the other crewmen (including Jai Courtney) shoot down the enemy fighters and survive this first encounter. The film flashes back to his childhood. Zamperini hails from Italian immigrants, struggling to be accepted in America. Zamperini doesn’t pay attention in Church and is picked on by other children. To keep him out of trouble, his brother involves him in athletics and running races. This film is either oblivious to clichés or doesn’t care. His brother motives him with cornball lines like “If you can take it, you can make it” and “a moment of pain is worth the glory of a lifetime”. Likewise, the racing scenes are filmed in ways which could never surprise us. Consider this set piece: Zamperini is losing his race. The film cuts to his family nervously listening to the radio. The commentators tell us he won’t take home the glory. Out of nowhere, Zamperini lays down his afterburners to win. Should we be surprised? It’s far more interesting to know Zamperini met Hitler at the games in real life.

Neither Jolie nor the script view Zamperini as someone worthy of a personality, but a symbol of Western individualism. We’re encouraged to reel in horror at Zamperini’s physical torture, the end of Democracy as we know it, and uplifted by his resistance to defeat. The obviousness of Jolie’s techniques, the fall then rise, never overcomes a monotonous transparency or that we’re asked to feel for a symbol before a person. This isn’t to say the film is devoid of suspense or craftsmanship. Jolie’s experience playing action stars filters into confidently structured sequences, including the aircraft scene and when Zamperini and two other soldiers, including Russell Allen Phillips (Domhnall Gleeson), are stranded in a life-raft for forty-seven days. Surrounded by sharks, the men catch fish from over the side of the raft and eat the raw meat. At the screening some jumped when one of the sharks emerged, gnashing its teeth, a predictable but exciting moment. But in this long sequence, strongly framed using long shots to express the isolation, the time is misspent. The script is completely lacking in personality traits and characterisation for either Zamperini or Phillips besides their endurance and some traces of faith.

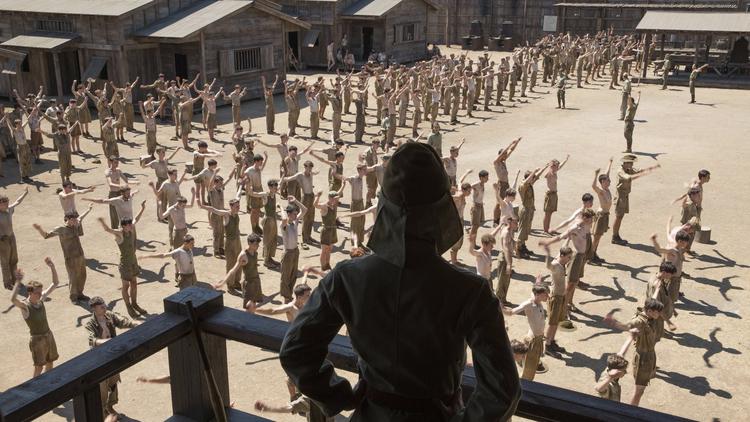

Once Zamperini and Phillips are captured by Japanese soldiers and imprisoned, Unbroken isn’t shaped by a plot or relationships but brutal, violent episodes, derivative of countless other enslavement films. The most confronting image here isn’t a beating but seeing Phillips’ starvation upon removing his shirt. It’s a terrible sight without the film overplaying its hand. But the psychology between prisoner and warden is overly simplistic and obvious. Zamperini represents Western individualism and loyalty to American values. In one rare scene outside the camp he refuses to continually discredit America on radio and is sent back to be tortured. His ideological counterpoint Mutsushiro Watanabe (Takamasa Ishihara), otherwise known as the Bird, is fascism personified. He extracts punishment and repression via a bamboo stick. Attempts to round this monster are frivolous. He tells Zamperini they are friends but he is an enemy of Japan but the line is recited with such overt menace we don’t sense a deeper connection between the two men. Some Japanese nationalists have called Unbroken’s representation of Asians racist. The Japanese soldiers were merciless to their prisoners. This is factual. But films like Clint Eastwood’s Letters from Iwo Jima have humanised Japanese troops in such a way that Unbroken’s characters look comparatively old fashioned and one-dimensional.

The film’s major confrontation, intended as a set piece of triumph, summarises the dramatic phoniness and ideological flaws. Zamperini is ordered at gunpoint by Bird to pick up a heavy beam and hold it over his head. If he drops it he’ll be shot. Bird waits, expecting him to fail and Zamperini to die. In this sequence Zamperini mirrors Christ, carrying the beam like the Cross. This is suitable, Zamperini was a Christian, until the film unknowingly characterises him in its own fascist, Aryanist lens. The supreme fitness of the American, his inhuman strength and willpower, leaves the Japanese officer stunned and diminutive. It’s a climax so unsubtle and appallingly jingoistic it becomes unintentionally funny. The prison content might have been more tolerable if it hadn’t entirely substituted the most interesting parts of Zamperini’s story. The forgiveness of his captors, attributed to his faith, and his leg of an Olympic race at eighty-one years old, aren’t relayed dramatically but lumped in an end text summary. Zamperini was ninety-seven when he died last year and before his death Angelina Jolie showed him the film in hospital. By all accounts, they had a very close relationship, like a father and daughter. Due to their bond she’s chosen one polite, safe angle for the telling story: the unwavering physical endurance of a single man. But for the wider audience, it’s not pride or liberation we feel but deep artistic constraint.

Summary: For the wider audience, it's not pride or liberation we feel but deep artistic constraint.