Black Mass – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on October 10th, 2015

Roadshow presents a film Scott Cooper

Produced by Scott Cooper, John Lesher, Patrick McCormick, Brian Oliver and Tyler Thompson

Screenplay by Jez Butterworth, Mark Mallouk, based on ‘Black Mass’ by by Dick Lehr and and Gerard O’Neill

Starring: Johnny Depp, Joel Edgerton, Benedict Cumberbatch, Rory Cochrane, Kevin Bacon, Jesse Plemons, Corey Stoll, Peter Sarsgaard and Dakota Johnson

Music by Junkie XL

Cinematography Masanobu Takayanagi

Edited by David Rosenbloom

Running Time: 122 minutes

Rating: MA15+

Release Date: October 8th, 2015

The title of Scott Cooper’s effective, violent and atmospheric crime drama Black Mass has several meanings. The first is a reference to the Irish-Catholic values of the film’s real life subject, the gangster James ‘Whitey’ Bulger, whose violent actions in South Boston from the 1970s to the 1990s were a terrifying contradiction of his religious upbringing. The second meaning is a scientific and philosophical viewpoint, reflecting how matter or mass can never entirely disappear but becomes invisible to the human eye. Invisibility was imperative for Whitey because according to the film, his attitude was that if no one witnessed a crime, particularly a murder, it never happened. The merciless brutality of Whitey is embodied by Johnny Depp, whose wicked performance and hideous transformation ignites a desperate victory for this once inventive character actor. He is matched by a colourful turn from Australian actor Joel Edgerton, who plays self-interested FBI agent John Connolly, a childhood friend of Whitey. Connolly represents another form of darkness. Money and status encourage him to sweep away the devil’s crimes, meaning Black Mass is a film that draws from the Old Testament, warning us about how people of power and status succumb to life’s temptations. The two lead actors and the complexity of their involvement to each other carried my interest almost entirely throughout an untidy but compelling and gruesome crime opera.

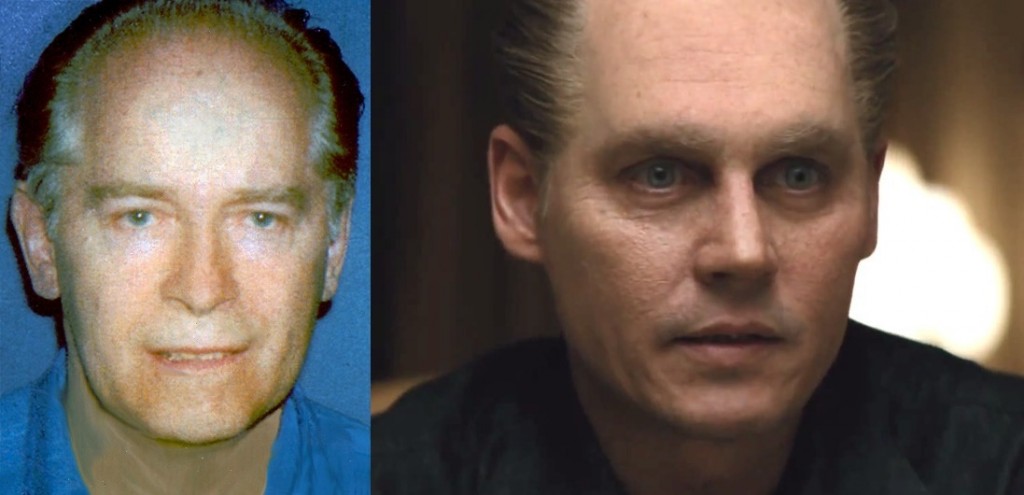

Most Australians will be unfamiliar with Whitey Bulger and unbeknown to what an irredeemable slimeball he was at the peak of his own self-made crime world. Plainly, Bulger was a protected species. He was involved with nineteen murders and convicted of eleven of them once finally arrested at age eighty-one. Previously, Bulger had spent time in Alcatraz where he was subjected to experimental drug testing. In between his incarcerations, Whitey was also of all things, an FBI informant. Given Whitey defended Connolly from bullies when they were children, Connolly (pictured below) offered him protection from rival gangs in exchange for information on the Italian Mafia—the primary target of the FBI. Despite being instructed not to murder anyone, Whitey and his Winter Hill Gang were free to engage in violence, racketeering, drugs and supplying guns to the IRA. Connolly bought off his fellow agents but Whitey was also shielded by his brother William Bulger (played in the film by Benedict Cumberbatch, with a rather jarring American accent), who was President of the Massachusetts Senate.

Some will prematurely assume Scott Cooper is pillaging solely from Martin Scorsese’s crime films, which is an overused reference point that disregards the ultra realism of the director’s dramas. Black Mass is more theatrical, closer to the classic gangster films of early Hollywood, like Little Caesar (1931) and White Heat (1949), which never glorified or romanticised criminals but painted them physically and mentally as monsters of society. Similarly, with his balding head, cold hard stares and bad teeth, Depp’s Whitey is an ugly beast. The film doesn’t ask for Whitey’s sympathy but illustrates the values that shaped his erratic and unpredictable behaviour. A darkly funny scene between Whitey and his son summarises his strategy for evading the law and stamping out his territory. To the disapproval of his wife Lindsey (Dakota Johnson), he tells his son that the only thing wrong with him punching a school bully was that he was caught doing it in front of other people. The lesson summaries Whitey’s perspective that violence is only effective when it’s invisible. While inspired by classic gangster figures, Whitey is also a composite of modern criminal figures like Henry Hill and Tony Soprano. The violence is juxtaposed against scenes of compassion and family, like when Whitey helps an old woman in the street or reluctantly plays cards with his mother, which stipulates Whitey’s controlled nature. Comparatively, Connolly is richly drawn as a conflicted opportunist. Whitey’s intelligence allows Connolly to enhance his public status, while attempting to convince his wife (and himself) that he’s acting out of prolonged childhood debt. The theme of enduring friendship borrows from Clint Eastwood’s Boston crime drama Mystic River (2003), further highlighting the contemporary pop inspirations.

The film’s core strength is illustrating the FBI’s powerful dilemma, caught between collecting information and turning a blind eye to Whitey, which consequently frees the character arcs from conventional Hollywood moralism. It is a Biblical cautionary tale about the price of loyalty, with its end notes suggesting Connolly paid heavier than anyone else for never parting from Whitey. The story was interesting enough for Scorsese himself, given Jack Nicholson’s character in The Departed (2006) is said to be inspired by Whitey. Due to the nature of the story and the number of characters, it forces the narrative to switch from side to side and leaves Whitey off-screen. Structurally, it feels untidy and made me long for those classic gangster films, which were only eighty to ninety minutes long. However, both small moments and longer sequences are memorably realised by the two shining lead performances. Johnny Depp’s interpretation is a chilling masterclass of mannerisms, where he uses the aggression of his eyes and a low creaking growl in his voice to accentuate Whitey’s callousness. This intimidating and merciless performance is a stark reminder of the actor’s capabilities with strong material and direction. In playing Connolly, Joel Edgerton discovers his ample charisma, turning his character into a showman before the media as his status rises and simultaneously fending off his wife’s doubts about the sharp rise in money he’s earning. Equally pleasing is how these actors look similar to their real life counterparts, particularly in stylisations like their haircuts and builds, and also the strong support by Kevin Bacon, Corey Stoll and Peter Sarsgaard in small roles.

Outside of controlling these actors, another distinction of Scott Cooper’s third directorial effort is the unflinching approach to violence. The killings in this film are not fun to watch, nor are they cool or funny. The deaths are brutal, merciless and almost unwatchable. That takes guts these days when films are compromised and designed to appeal to mass markets and younger viewers. The violence also removes any trace of Whitey being glorified. His maneuvers were thought-out and cowardly, leading people into rooms or river banks followed by execution style killings. A minor flaw in the morose tone of the film is that the music score telegraphs the film’s intentions of being operatic in mood. But after all, it is a bloody crime opera. Even before the blood spills, Cooper shows a deft hand for suspense, threatening us with a character’s fate moments before Whitey strikes them down. Or perhaps not; some scenes are nail biting in subverting our expectations of Whitey’s violent behaviour. One example is a gripping standoff at a dinner table, which ranks as a recent career highlight for Depp. His haunting performance is a significant contributor to the film’s tension levels and the narrative’s tragedy that Connolly developed all his profile from such an immoral creep. Perhaps then Black Mass is a contemporary social reflection rather than an ode to classic gangster films or a Bible passage. Its cautionary statement about the cost of loyalty isn’t dissimilar to modern shows like HBO’s The Wire, where law and crime inseparably converge, and society’s own blindness is when we are no longer able to separate different sides of the law, as people of religious and political rank tumble towards the pitfalls of social status and capitalism.

Summary: The two lead actors and the complexity of their involvement to each other carried my interest almost entirely throughout an untidy but compelling and gruesome crime opera.